Nick Mason's recent autobiography, Inside Out, recalls his unique experiences as the drummer for Pink Floyd during for over three decades — he is the only member to have remained with Pink Floyd throughout the complete duration of the group's career. The book contains a startling degree of detail. Where Mason's candescent memory falls short, he draws upon his former band mates and colleagues to fill in the blanks. Mason's book sheds some light on many of Pink Floyd's early recordings where little has been previously documented. The band's experiences in the late sixties at Abbey Road Studios were mostly overshadowed by The Beatles, who through their mutual label EMI, afforded Pink Floyd the financial and artistic freedom they needed to experiment and ultimately realize their potential in the studio.

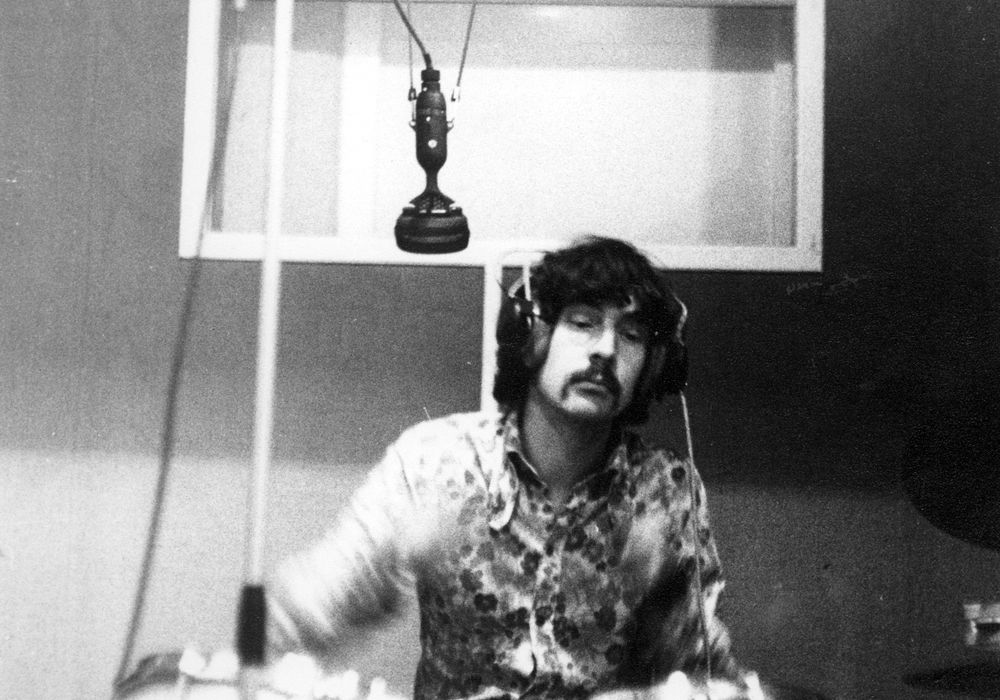

Following the group's initial success with singles like "See Emily Play" and "Arnold Layne," following their Norman Smith-produced albums Piper at the Gates of Dawn and Saucerful of Secrets, Pink Floyd effectively began self-producing their own records until The Wall, over a decade later. The group managed its own destiny in the studio, and needless to say, vastly expanded its creative frontiers. It is clear that the group's collective imagination and experimentation was the driving force behind their success, rather than any special kind of recording technique. However, their unique method of composition and artistic expression provided unprecedented challenges for engineers to capture these recordings even at Abbey Road, one of the most advanced studios of its time. Mason also made his own forays into production, working with artists like Robert Wyatt, The Damned and Gong.

Despite Mason's immaculate rock pedigree and enormous success, he remains friendly and approachable. I spoke to him just as he began promoting Inside Out to Eastern European countries, a reminder that his many years of music with Pink Floyd has resonated and endured with fans on a truly global scale.

When you started writing Inside Out, did you realize how big of a job you were getting yourself into? How complex did the project turn out to be for you?

It was much bigger than I anticipated. If I had perhaps thought long and hard about it, I probably wouldn't have started it anyway. So, it's a good thing not to think too hard about what might be ahead. I certainly changed horses in midstream a bit from when I started, which was going to be the ultimate, official biography of the band with every detail in it, and perhaps long sections from every recording session and gig we'd ever done. As time went on, it just became more and more obvious that it was more interesting to simply do my version of events and let it sort of spin on a particular speed, than try to cover every different version of everyone else's version of what happened when.

Do you have any early memories of recording at Sound Techniques in 1967, before you went to Abbey Road? I'm thinking of the singles "Arnold Layne" and "See Emily Play." The drums and bass were so tight and there was such a great bottom end.

I think we recorded on 4-track. The drums and bass were laid down on two of the tracks, guitar on the third and then all bumped down to the remaining track to free up three tracks for overdubbing vocals and Farfisa keyboard. The Sound Techniques sessions were much more to do with John Wood and Joe Boyd producing and coming up with the sounds rather than us. During the Sound Techniques sessions, we didn't have the time that we later found at Abbey Road. We were actually in there to get the single made.

In your book, you cover a lot of the creative experimentation that went on in the late sixties. Take "Saucerful of Secrets," for example. Can you talk about how this piece evolved structurally and compositionally?

Well, as far as I remember, we didn't actually try to notate what we were going to do, but we did try and draw up some sort of chart of what was going to happen. So, there was some sort of graphic representation. I think it was based loosely on having a sort of classical piece in terms of having three different movements. Then the movements were worked on as individual pieces. The whole thing was assembled further down the line. I can't actually remember how we worked out the middle section, which is basically a drum pattern double tracked and then looped — why we chose that particular pattern or how we ended up with it. I think the three ideas were that there was this grand finale, the Hammond organ section. Once we played it live on the Albert Hall organ and it sounded fantastic.

There are a lot of interesting dynamics in that song, especially when it comes to the drums. You start with soft accent cymbals, then comes the hard crashing, including Roger [Waters] with the gong, then the repetitive pattern and then the mellow finale.

That was the thing that perhaps made it different and where we found a niche for ourselves, doing pieces that weren't actually full volume from beginning to end. That was the beginning of finding new sounds or new tones — particularly that business of taking the microphone to the very edge of the cymbal on that first section. It was very much something that we discovered in the process.

I know the Atom Heart Mother sessions were challenging for you because you had to play the entire track straight through with Roger without stopping because you couldn't splice?

Well, yes. EMI had a sort of house rule that because these 8-tracks were new and no one had worked with them, nobody could splice the tape. Frankly, everyone was scared of trying to splice it! Looking at it now, after the event, it was really daft. It would have made life a hell of a lot easier for everyone if we could have spliced it. It was a directive from Abbey Road that splicing 2" tape was not to be done.

What were some of the challenges in recording Atom Heart Mother and how rewarding was it to have finally completed it?

I think it was difficult because we were doing something we didn't know very much about, which was this rather overextended sort of piece, and it involved the orchestra as well. It was difficult for Ron [Geesin], who I don't think had done much work with orchestras. I think most of us feel, listening back to it, that it's a rather flawed album. We could have done a lot better if we had known how to tackle it.

Given the fact that Atom Heart Mother was mixed in quad right after its original release, wouldn't this be a great candidate for a 5.1 surround mix? Has anyone at the Floyd camp considered this, or are things focused on the later catalog?

I think we've tended to focus on the later catalog. It's an interesting idea. I don't know what condition the original masters would be in, and I don't know to what extent we could clean them up. It would be an interesting project if one could clean up the masters and actually improve things like the drum sound. The drums are very much subject to spill. Actually, what's happened is that they've spilled onto the orchestral sections.

The mics picked up not only the orchestral players, but also the monitors playing in the live room?

Yeah, and they had to play them loud because of the slightly erratic timing and all of the rest of it. One tends to assume that the purpose of re-mastering is to improve the sound quality, but there might be a case to be made to improve the balance at the same time.

Was Atom Heart Mother rewarding to take out on the road?

It was bloody difficult. I think traveling with anything like that — I mean, you've got a whole bunch of people who really are delightful, but not committed. The whole logistics of traveling them and recording them and mic'ing them up — frankly, I would have said we were pretty relieved when we got back to being a four piece.

In your live performances during that time, you played things like The Man Sequence, which included tracks like "Beset by Creatures of the Deep" and other songs. Did this framework ever come to fruition like you wanted it to? Clearly they were early efforts at a more conceptual musical piece.

It was the forerunner of Dark Side in many ways. There were a couple of elements to it. But the main thing was the idea of a band really doing the whole show. In the late '60s and early '70s there were support acts, and if it was America, there would be two support acts. The idea of this was that we would do our own show and it was a seated "concert", not a gig, if you like. The Man, the whole evening, was called something like The Massed Gadgets of Auximenies. The first section was called "The Man", and the second section was called "The Journey". But basically, it was a mixture of songs, bits of music and just sort of odd things that were done onstage. For instance, "Alan's Psychedelic Breakfast" was performed live with actual cooking going on onstage.

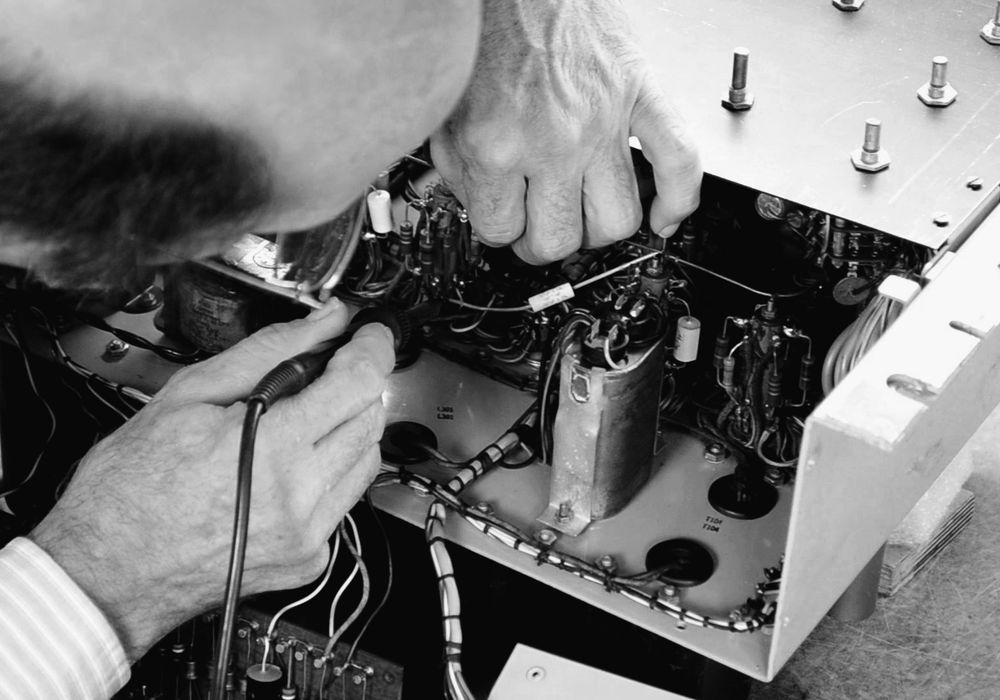

Can you talk about the Azimuth Coordinator that was built on specification for you by Abbey Road? During this time, were you increasingly using sound effects in the studio and on the road?

Well, we were probably just beginning to mess about with sound effects in the studio, and we met this engineer at Abbey Road — he was a maintenance engineer called Bernard Speight. It was absolutely his concept, I think. It probably existed as an idea, but he said, "Look, I can build you this thing." He built the original quadraphonic pan pot, a pair of them, and worked out how we'd use them, what speakers we'd need and all the rest of it. Of course once we started messing about with it, we realized the potential for running tape and running sound effects, particularly in live shows, around the concert hall.

Do you think that your education in architecture gave you a predisposition towards the technology? It seems like you were pushing the engineers ahead just as much as they were pushing you in terms of technology.

I don't know. What I would say is that it was a very useful grounding. There's a very real mixture of technology and art, so it certainly gave us an idea of how to make things, how to plan things and how to make graphic representations of what one wanted to do.

Of all the people that you worked with throughout your career, can you think of any that stand out as bright stars, who helped you get to the next level either technically or creatively?

I think most of the people we worked with were terrific — it mostly has to do with the timing. Joe [Boyd] was fantastic for the early singles. Norman [Smith] was good news because he taught us a lot and gave us a pretty free hand in the studios. This was a period where producers were expected to control the band, save money and save time.

Norman played a lot of instruments, right?

Yeah. He was the sort of junior version of George Martin. And that's definitely what he was aiming to be, I think. I'd also cite people like Bob Ezrin [Tape Op #31], James Guthrie, Alan Parsons. Frankly, if they weren't any good, we probably would have gotten rid of them or did get rid of them before they got their name on the album! [laughs]

At what point was it when you really felt you had free reign to make your own production decisions? This happened quite early on, correct?

I think Saucerful of Secrets.

EMI was pretty cool about that?

Yeah, because I think the work had been done by The Beatles, who had shown them that if they just allowed the band free reign in the studios, that they'd probably get something really good at the end of it. The recording time wasn't quite as expensive as it later became, and the studios were busy — but they could afford to give the time.

Very few live recordings have come out of Pink Floyd's early career, except for Ummagumma (the live side) and the film Live at Pompeii. But there are a whole host of high quality bootleg and BBC recordings out there that capture some inspirational performances by Pink Floyd, that reveal a completely different dimension to the band. Have you guys ever looked at cleaning up and releasing the BBC Paris Theater performances from 1970 and 1971, for example?

Well, we always look at that sort of thing. But the fact of the matter is that when Pompeii was done, we knew it was to go out live as a film. So, we're very comfortable with how we did it at the time. The problem with things like the BBC and the Paris Theater recordings is they were done as one-off radio shows, and it was never our intention that they would be left to posterity. So, we're less enthusiastic about that.

You spent a great deal of time on the road and in the studio going into the seventies. Where did you do most of your writing? Did you actually write lots of things at Abbey Road?

There is no specific answer to that one. There were certainly some, like "Careful With that Axe" or "Saucerful of Secrets", done in the studio, designed in the studio and carried out there. Then there were songs that generally were written not on the road, but at home by individuals and then brought in as complete or semi-complete pieces.

Would you say that "Shine On You Crazy Diamond" was composed in a similar way to say, "Echoes?"

No, a mixture — funnily enough. It was done partially in the studio and as sections brought in by individuals.

Can you tell me a little about the "Household Objects" session that occurred after Dark Side of the Moon? What was the goal of this?

I think it was just a desperate attempt to find some new things to do. It was an experiment — it was a failed experiment that was consequently ditched and we moved on. We did spend a lot of time on it, though.

When you look at Pink Floyd's early catalog, the framework appears to be a much more free-form approach than say, Ummagumma or Atom Heart Mother, Dark Side of the Moon or Obscured by Clouds, when it appears that compositionally, things become more structured. Was there a catalyst that led to a more structured approach?

No, I don't think there was. I just think we drifted towards found opportunities or things we liked doing. I think probably when Syd [Barrett] had left, there was more of an interest in, I won't say designer songs, but I think Roger's songwriting was the biggest change. Once he really started writing, the ideas that came out of that were frankly, not psychedelic. They were organized, intellectual pieces.

What about the period around 1974, when you were writing "Raving and Drooling" and "You Gotta Be Crazy?" You were presumably spending a lot less time with one another. Were you still gelling together as a band at that point, or was it more individualized?

Hard to sum it up, really. By '74, we were spending less time together, because most of us were married and having children. You know, it was about growing older, frankly, as much as anything else. People tended to work a little more individually. Most of us were doing bits of production for other people. There was less of that completely focused "all four of us working to achieve exactly the same end."

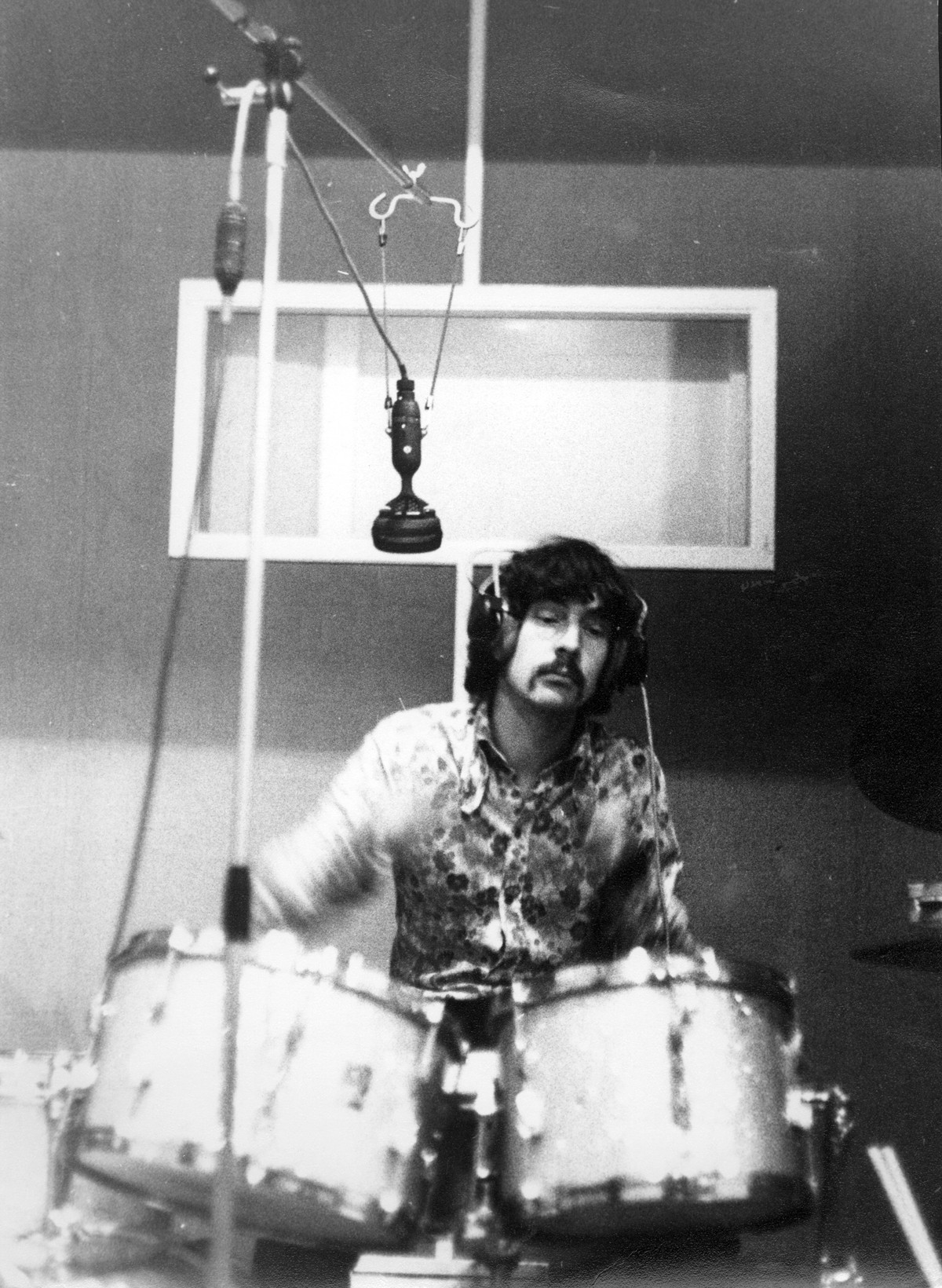

You obviously have a very distinctive drumming style, and I'd be very interested to learn about the kind of care that was taken to get the sound of your drums on tape. I'm thinking of Dark Side of the Moon, where your drums just sound perfect.

Well, I think particularly in the early recordings, people took acoustic instruments very seriously. I'm sure they still do, but drum sounds were the test of an engineer. Whether it was John Wood or Alan Parsons, they took it very seriously and tended to use the same mic set ups of Neumanns for the overheads and AKG D12 for the bass drums. There were very specific ideas of what was best for the drum kit. James Guthrie was great on The Wall — I thought he did a great job. It almost became a dying art — engineers who spent so long recording orchestras and had a very clear idea of how to record acoustic instruments.

You spend many, many years doing sessions at Abbey Road, but then made a departure for recording Animals by going to your own Britannia Row. Presumably, you knew the ins and outs of Abbey Road and it was familiar territory for you. Was it a big change?

We'd worked in other studios by the time we went to Animals. We'd worked in Air London — we worked in France at Chateau D'Herouville for Obscured by Clouds. And we'd done film music in Pye, in Marble Arch, and stuff like that. Abbey Road was great but it was quite an old fashioned place in a way, and most of the other studios were more cutting-edge and a bit more modern in feel. "Groovy," I think, would have been the word at the time. Britannia Row was certainly a big change, because it didn't have anything like the same facilities. But that was rather good from our point of view. It kept things simple.

In the late seventies, you got into a little producing yourself. You produced The Damned, right?

Yes. Music for Pleasure. I also produced Robert Wyatt, a band called Gong, with Steve Hillage, and a few other things. The Damned chose me because they couldn't get Syd Barrett. [laughs] I think it was probably better for me than it was for them. They were sort of fighting amongst themselves at the time — physical and musical differences, perhaps.

Did you enjoy being a producer? How did you fit into that role, being on the other side as an artist for so long?

I really liked it. It was really good fun.

What are you up to now that the book is out?

Well, a lot of more work to do on the book, because there is promotion to do on the paperback. It's going to print in Czechoslovakia, Romania and Bulgaria. The rest of the year I can see a lot more stuff that has to do with that book. To be honest, I really enjoyed writing and perhaps I'll look to write something else. I'm really pleased with the way it's gone in America particularly. It's been great and people really seem to be up for it.

_disp_horizontal_bw.jpg)