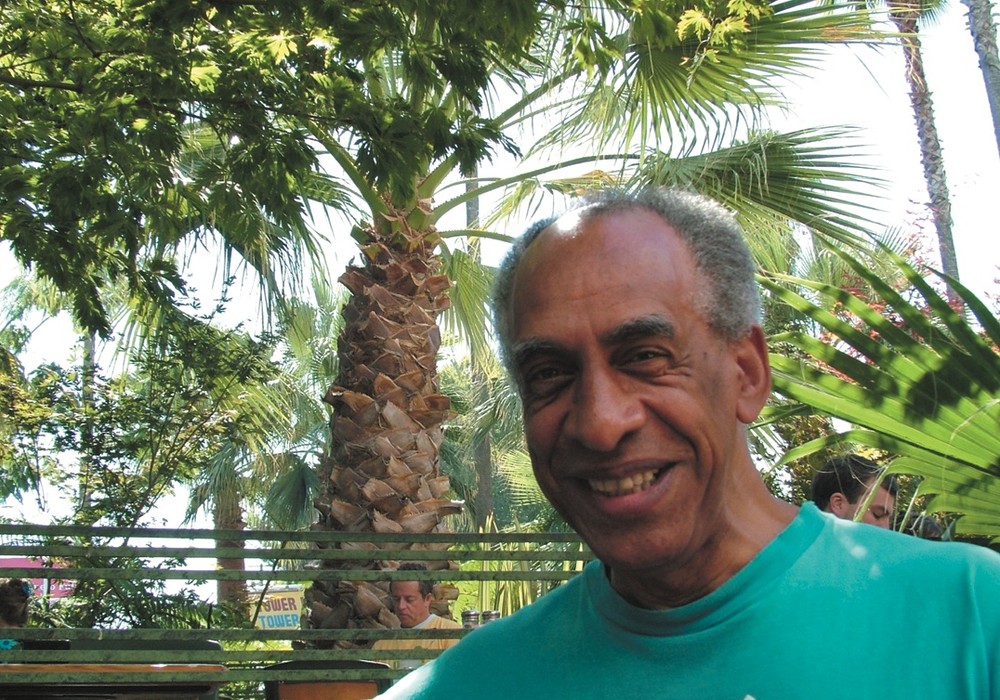

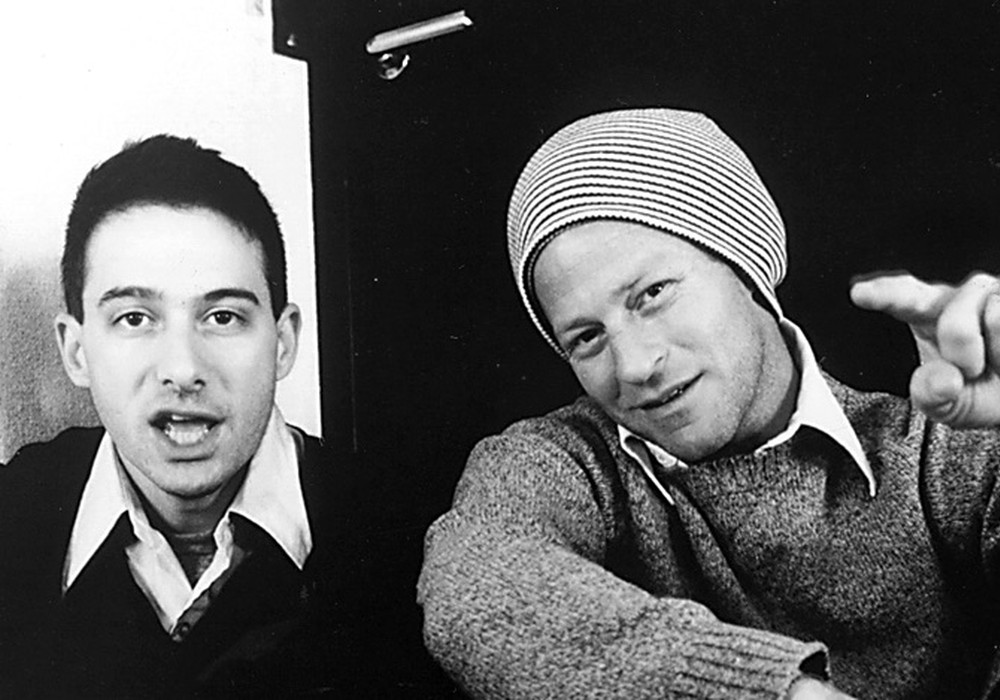

As a house engineer for Death Row Records, multi-platinum engineer Tommy D recorded and mixed classic albums with Dr. Dre (Andre Young), Snoop Dogg (Calvin Broadus Jr.), and 2Pac (Tupac Shakur). Before that, he worked with Prince and George Clinton. This former blue-collar Iowan fell upon the L.A. rap world at the turn of the millennium and established himself as an unflappable go-to architect of what would become known as "gangsta rap." Shortly before his untimely demise, Tupac finished his classic The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory album with Tommy D, who had become known as the only engineer the mercurial artist would work with. Maybe it's because he's one of the nicest guys in the business.

How do you characterize mixing for Tupac and Dr. Dre?

The fun part about mixing with Death Row was when I realized that they wanted the shit pounding, and I said, "Okay!" The first thing Dr. Dre asked me was, "Can you help me with the levels?" The tape machine was in the red, the meters were slammed, and he said, "Are the levels okay?" I said, "I guess." [laughs] It was seriously in the red...

And everybody always wants more low end.

Every day, every song. Like the Makaveli album [The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory], I hear about that all the time; that has the most bass ever in a rap song. That's why I developed the triple EQ method, because Tupac kept yelling at me that there wasn't enough bass. So, I ran the sub bass through a 30 Hz [EQ boost] and reprinted it, but then cranked it through. I ran it again through 30 Hz and printed it again on the tape. But I printed it low enough so I could run it through 30 Hz again. So, three times I run it through 30 Hz; by the time it was triple printed, it was still at zero [dB, on tape]. It was 30 Hz three times, so that's, like, four times 30 Hz in it. But there's no distortion or overloading, because I printed it four times.

Yikes!

Well, you have to think fast in this situation. When you're getting yelled at by Tupac, you've got to think of something real quick. It was like, "Okay, I'll just print it." From the very get-go it was strange, because nobody ever told me what to do. I came in and the needles are fucking slammed, but it sounds great through the speakers. I never went to engineering school, so I'm looking and I don't think that's right, because there was a lot of red there. But I'd never heard the drums sound like this, slamming like this, before. So I said, "Your levels are fine, man." I'm back there looking at the levels, and I didn't know when we played them back if they were going to sound okay or not. But there was no distortion with Dr. Dre. Even though we were slamming those needles on the tape, it didn't mean there was distortion. That's when I realized you can't go by your eye on the tape machine VU meters. We never aligned the tape machines. You couldn't align the machines in a rap gig. So, for two years, we never aligned the machines.

I worked in a studio in Haiti where they had never aligned their Otari 2-inch machine.

If you tell dudes that have got a 4-hour session that you were going to spend 15 minutes aligning the tapes, they weren't going to hear that. In one of Kurupt's [Ricardo Emmanuel Brown] raps [Tha Dogg Pound's "New York, New York"], he goes, "I'm simply laying hoes like SMPTE, the invincible MC." I asked him where he got that SMPTE line from, and he said, "I hear you guys talk about laying SMPTE all day. You play with SMPTE, and I'll be back in 10 minutes." There's none of that these days. That was our only break – we loved it when the tape machine broke down. There was no Pro Tools back then, or at least no stable Pro Tools.

And are we talking about two 24-track machines synced together?

No. Dr. Dre said, "If you have to go over 24 tracks, there's something wrong with your song." He had a point. One time, up at Dre's house, I said, "Well, let's put it on tape, just in case." And he said, "There's no such thing as putting stuff on tape ‘just in case.’ Either we'll use it, or we don't." And I thought, "Yeah, that's right." That's when I realized that there was that one sound that makes the song. He was always looking for that one sound; that one sound that made everybody go, "Yeah!"

When he first started using Pro Tools, Bill Laswell [Tape Op #93] told me that he saw the danger would be too many options. You're not committing the way you have to with tape.

I guess, but you can still use that approach of, "We're going to commit." Although, if you have somebody putting a bunch of parts down, that could lead into something else. With Pro Tools you can compose and track at the same time, as well as orchestrate, mix, and whatever. Work on another song, while you're doing a different song.

You said Dr. Dre is a producer who finds the sound for each song to make it go.

And he also has a plan, a reason why the song is being done. We were doing "Natural Born Killaz," and he doesn't really like to be in the studio that much. He wants to get a killer song and get out of there! He'd rather pound out one badass song in a day. We'd be working at his house, and if he couldn't come up with a song in two or three hours, he'd say, "Man, fuck today." But there would be times that we'd be sitting there for ten minutes, and then, "Bam!" To see some of those ideas come to fruition is awesome.

How much would it happen where gears would get shifted in the middle, from happy accidents?

Those are usually what I call musical mistakes, or something that no one expected to happen. That's where the live musicians came in. He might get an idea of something to play, they might play something to what he's got going that's perfect, and he'll be like, "That's it." But what happened with live musicians was like samples and loops. He'd have them play consistent the whole way down, but of course it's not going to be perfect – if you want to sit there and analyze it – so it loosens the groove up a little. For Prince, I had to have all the loops ready; that early training was indispensable. It was just a job, but I happened to get it. [laughs] To set up the options ahead of time can get complicated, but I got pretty good at it. I said to myself, "If I can learn all this shit, I'm pretty valuable." Plus, it was fun! I wanted to be able to run all the gear.

Do you put anything on the master bus to hold it all together when mixing?

We were using the SSL [console], so we used the SSL compressor. All Death Row projects were done on SSL to tape.

Sounds like Death Row paid for a lot of studio time.

We had the studio booked for two years! I went over to the tape vault one time, over at Warner Bros., and I'd never seen anything like it in my life. There must have been thousands of rolls of tape, plus video, and I saw my handwriting on all these reels. All the artists I'd forgotten about. How much did I record? Suge [Knight, Death Row's CEO] was trying to make a deal with Sony, but he blew it so all that Death Row stuff we did never came out.

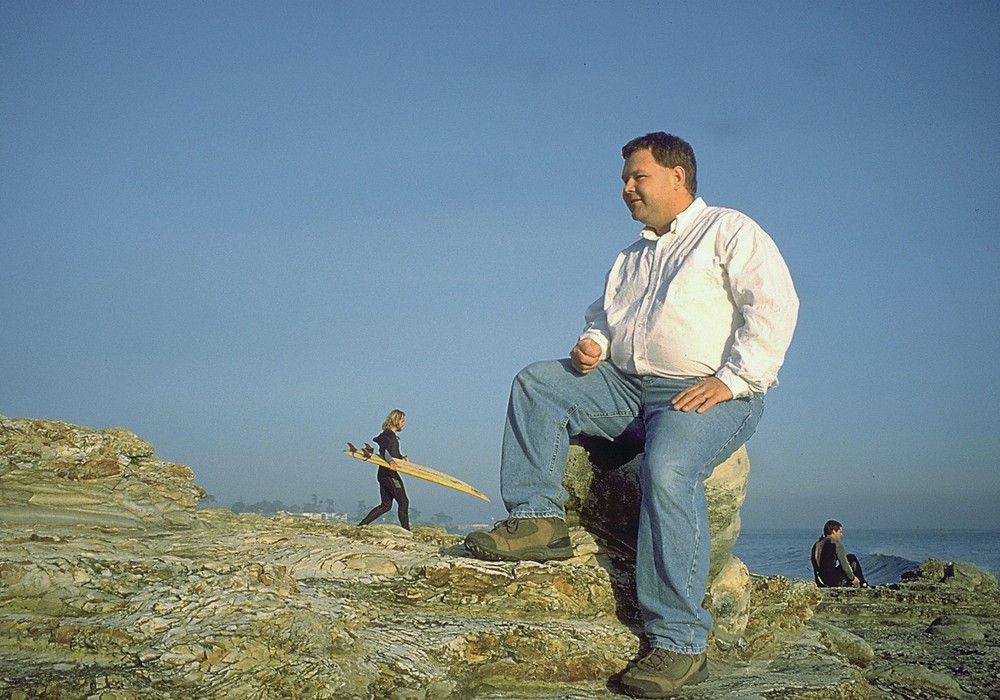

How did you start with Death Row?

Keith Cohen and I were working on so many remixes at Larrabee West, after we were working with Prince. Prince had gone to London and Death Row was next door. They beat the engineer up. The studio owner came over and said to me, "I need you to go in the other room and be the engineer."

Because the other engineer got beat up?!

I think they punched him in the face or something. It's okay to talk about it now because those days are over with, and half the people involved are dead. I always said, "If the studio's on fire, I'm going to print the mix and get out the door before the place burns up. I guarantee it!" I used to have to mix under some pretty unusual circumstances. There's a guy getting beat up in the back room, or a dog fight going on, or they're threatening to beat up the assistant engineer because he messed up the food order.

How did you deal with those working conditions?

I used to just keep doing what I was doing. It would be a situation where it was like being a chameleon. If I walk in to mix a Spanish flamenco guitarist, then I have to be prepared to act and do it their way. If I walk in and they're shining their guns, and they have a song they're going to mix but they're still waiting for the guy to show up with the tape because his brother's car got stolen. They don't want to be on the clock just yet, so you say, "No problem." You don't say, "Man, I've got to charge you from the time you've been here." That's getting off to a bad start. It's all about winning over the confidence of the artist.

And the record company side was notorious with Death Row...

Here's when it really flipped me out: When I went over to Jimmy Iovine's house with Dr. Dre, and he made Dre the offer to leave Death Row. It was the night Tupac did "California Love" on Saturday Night Live [February 17, 1996]. We're sitting there at dinner, and they were cutting a deal. Dre was leaving Death Row in the morning, and I'm like, "Fuck, man!" Then we were watching Tupac on TV. I go to Death Row the next day, but I'm not going to say anything about Dre jumping ship. Tupac was already upset, because Dre only did two songs on All Eyez on Me. I think Dre was unhappy with Suge [Knight], what with people not getting paid or receiving production credits. "His methods were unsound," to quote Apocalypse Now. [laughs] Dre didn't want to do Nate Dogg's [Nathaniel Dwayne Hale] record for the same reason. Dre didn't feel comfortable with what was going on at Death Row, in terms of the distribution either. He didn't want to do a whole 20 songs with Tupac. When Tupac came to Death Row, I went to his house and they told him, "Tupac's here. He got out of prison and went to the studio." And Dre said, "That's it. Now that Tupac's here at Death Row, I've got to get out of here." At Death Row, you went to work and had no idea what was going to happen. The less you knew, the better. Heron [Aaron Palmer] was head of the whole Death Row security. He was murder for hire, and I knew when I'd made it at Death Row when he said, "You've got to come outside and check out my car, Tommy. Go out and check on my car." I go out there and there are bullet holes all down the side of his [Jeep] Cherokee. He goes, "You should see what their car looks like!"

Yikes! Rough stuff.

And then he goes, "Tommy D, I've got to tell you something, man. I don't know what it is about you, man, but some of the hardest motherfuckers, and motherfuckers who don't even like motherfuckers, them fuckers like you. And Suge said, 'Make sure nobody fucks with him.' So, you don't have to worry about shit. If anybody fucks with you, you come and talk to Heron." I said, "Okay, cool."

So, they always had your back?

Heron's dead now. But you know what's crazy? I knew he was going to get killed, and he knew he was going to get killed. But they accepted the fact that they could get blasted at any minute. There were, like, two people a week that got killed at Death Row.

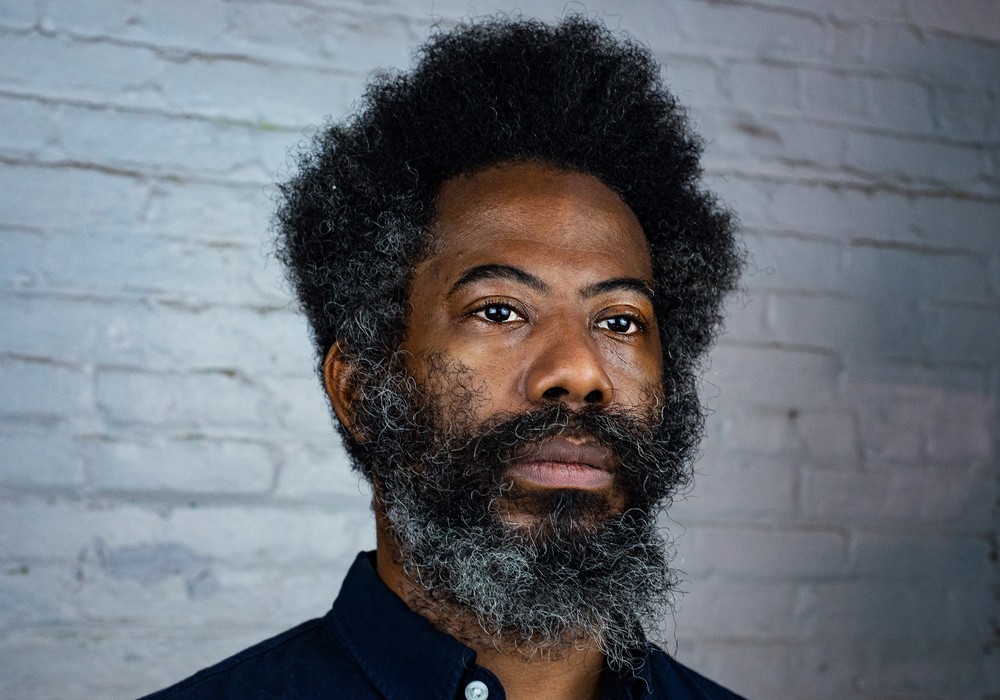

What was Tupac like, musically?

A genius, because of the way he did rhythms, the way he put the words down, and everything. He knew what was going on, he understood it. But he was all about speed, too. He'd get so pissed, "Those motherfuckers spent a whole day mixing that song? Man, we could have mixed the whole fucking album!" He couldn't understand why someone couldn't mix a song in ten minutes. One time he told me to put up some song, and he was sitting there, twiddling his thumbs, not doing anything, and I'm thinking, "Man, something's wrong. What's going on here?" I'm playing the tape, I was doing a mix as fast as I can, and he wasn't saying nothing. I said, "What's up?" And he said, "Is it mixed?" I said, "It's pretty much mixed," and he goes, "Okay, so run the DAT." And the next time down we ran it to DAT, and that's the mix that went on the record.

Tough circumstances to do a mix!

Some of the songs that went on that album were mixed in like 20 minutes. For real. But when you've been at Death Row studio for a year and a half, and you've done the [Roland TR-]808 and here comes the snare again, it's like cooking another hamburger at McDonald's. But here's the thing about Death Row. I don't think any of us realized how big it really was. I was over at Snoop's house, showing him how to run the Korg Trinity [keyboard], and there's a Snoop bass sound [setting "A62 SnoopDoggy Bass"]. Snoop says to me, "Is that big time if Korg has a bass sound called by your name? That's big time, right?" But Snoop was serious, and I said, "Yeah, that's big time, Snoop." He didn't know! It's how clueless everybody was, because everything happened so quick.

How do you see your role as an engineer, in general?

We're giving the musicians, and bands, the opportunity to see what they could sound like, because they might've never had the chance to record under good circumstances. Imagine your band gets a record deal and you get stuck with some engineer that sucks. It could ruin your chance of making it; this guy could ruin your record because he's an idiot. I can see where bands were stuck with engineers that screwed them up. That's how I survived with Death Row. I was in with it, I was down with the homies, and I was into what they were doing. If you're not into it, how are you going to do a great mix? If a dude says he wants a beat like this, that's what you do. You don't say, "That's not how it is done." I had a rule that I would never say, "No, we can't do it." No matter what they'd say, I said, "Okay," and I never used negative words.

The credo of Tape Op Magazine is that it's about creative recording, and not about saying there's only one way to do this.

Right! But part of being creative is being creative with the people. Once you get them comfortable, and they know that everything's cool, then it's a whole other situation. It's not your way when you are an engineer, it's the client's way. But if you're good, and they trust you, it is going to be your way if you gain their confidence. Or, if you're already famous, or whatever you want to call it. Hopefully they hired you because they trust you, and they assume you're going to do a good job.

And you weren't coming from a school program for audio engineering...

They were asking me to come speak at AES [Audio Engineering Society], and I went there and talked about what happened. They said, "Which school did you go to?" And I said, "I didn't go to school!" The dude stopped me and totally blew me off when I said that.

Some people take the formal educational side a little too seriously.

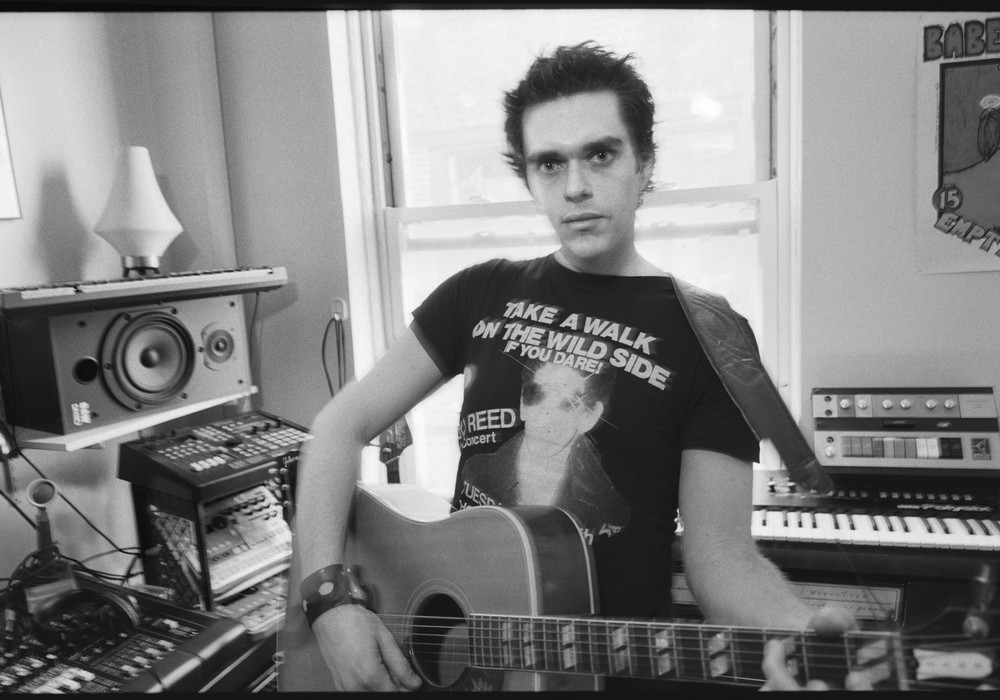

I tell people trying to get into the studio, "You don't need to go to school." They should have kept their money, bought a tape recorder, a vocal booth, and set up on Hollywood Boulevard. When I got into Pro Tools, I put a portable studio together to go around to people's houses. I had two cases with a Mac, two [KRK] K-RoK speakers, a little [Digidesign] Mbox, and a mic. Half the time the reason they called me was that they couldn't get Pro Tools to work; they'd be all screwed up.

Your old room didn't have any acoustic treatment, but it sounded great in there!

It was just a room, but that's how it goes these days. It used to be two turntables and a microphone, right? Now it's two speakers and a computer. That's the way I look at it; it's all about the computer and the speakers. I've been doing this for so long that I already know where it's supposed to be, as far as how it sounds in the room. After you've been doing it for a while, and you've mixed a thousand songs...

I was surprised at how loud you monitor.

When I started out, it was always loud; it's always been loud. But that's why I don't do a lot of rock, because it makes it hard to mix with distortion in it. I was trained by Keith Cohen to make everything clean. When I became Dre's engineer, it was all about clean, gates, the space, and not even using reverbs. For distorted guitars, sometimes it's hard for me to figure out where exactly it's supposed to sit.

How do you deal with the low end? That's the hard part, right?

No, that's the easy part – it depends on what I am dealing with. If I get a tune with no low end in it, right there I've got to start thinking fast. Remember yesterday, where I took the kick and shot it down an octave? I was thinking, "What have I got to work with here? I've got a kick, a snare, and two overheads."

And you split each track into separate new tracks for each individual drum component?

What I did first was the snare track, because he had what I thought at first was a wood block, but it was him hitting it with the side stick. I wanted those separated, for sure. I could put a little reverb on the stick, and I scrubbed out all the noise between them. I could have done [Avid] SoundReplacer and triggered another sound, and that would have been taken care of; but I always want to keep as much of the natural drum [sound] as I can. I'm still going to use the overheads as a whole, as a blanket, because that's the only way you're going to get the separation. The best part was that the guy was a good drummer; the kicks were consistent, and I really do start from the kick and build up. I go back and forth, because, as you saw, I separated everything out. I put them up, and pulled them down to still get in the groove, so I know what we've got. It's like when you paint a house, you have to scrape it first, which is no fun. But it makes a huge difference!

How much are you recording and mixing? Or do you get a lot to mix that's been all over town?

When I started out, working for Keith Cohen for Prince, we were also doing the George Clinton record [The Cinderella Theory] and all the tapes were coming in. It was just him and me at Larrabee West.

Probably from some pretty funky studios!

Yeah, most of it was from Detroit, with no track sheets and no clue of what kind of drums he was using. Some of it was completely amazing, but some of it we could tell that one guy did some drums, somebody else did some bass, and then they might have lost track at some point... [laughs]

Keith Cohen was a mentor to you?

Because of him, that's how I got into the business. Prince took his programmer, and I had been working at SST, Synthesizer Systems Technology, renting keyboards, as well as going around to the studios and showing them how to run the [Akai] MPC with all their keyboards. I was on call 24 hours, and that phone would be ringing all day with questions. Here I was with all these synthesizers, running this company, taking gear to Michael Jackson sessions, hooking them up, and not even knowing what I was doing. I had to learn on the fly, and I couldn't admit to anyone that I didn't know what I was doing.

And a lot of MIDI and sequencing didn't work great in those days. I'm sure it wasn't fun sometimes!

Luckily, at SST we always had the new gear, so we could make it work because we were in communication with all the companies – they wanted us to have their rental equipment out there working. I'd probably do ten setups a day, going around to studios doing setups, and then getting phone calls. This is without training about computers or anything. What I started to realize about using the manuals was that it's like learning another language. I'd have to learn Ensoniq, Korg, and Roland, and then I had to learn how they were going to talk to each other. But luckily the [Akai] MPC60 came along, and that thing was solid as a rock. A good rap producer could go nuts with that.

Before that it was the E-mu SP-12, right?

Yeah, but it was fairly limited. You couldn't tie keyboards up with that, you could just sample with it. And that's why New York music sounded like it did. They didn't get the [Akai] MPC60 and the keyboards going until it was already a West Coast thing. When I was working for Prince, we had to keep busy, even if he wasn't there. So, I had to make as many loops as I could for the [Akai] S1000. They said, "Have about 50 loops ready to go. When Prince walks in, he wants to hear loops. Not only do you have to have loops ready to go, but they have to be perfectly in time. And I don't want to hear one flam." Last night I did ten songs with El DeBarge. I was playing loops, mixing loops together, and then he would yell, "Yeah, that!" He said he wanted ten beats, "Give me something funky. Something up-tempo." I started taking beats from wherever. I could just grab them on the fly and then make it happen.

Last thoughts?

The worst thing about working in the rap business was the stigma that was attached to being tagged as a rap engineer. Engineers that did the "civilized" gigs were assuming that it was a job that anyone could do, that you were a hack engineer that didn't care about the laws of engineering. I'd like to have seen a couple of those guys thrown into the studio with 20 people that expected them to be fast, no mistakes, and keep the session going even if the speakers caught on fire. [laughs] Dave Aron got the award at Death Row for torching three left side JBL [monitors] on a Snoop [mixing] session! To this day, I still haven't been able to pull off that one. The laws go out the window, and the music had better be pounding or you're gonna be left behind. You decide what to do when Wu-Tang Clan ain't happy with the mix!