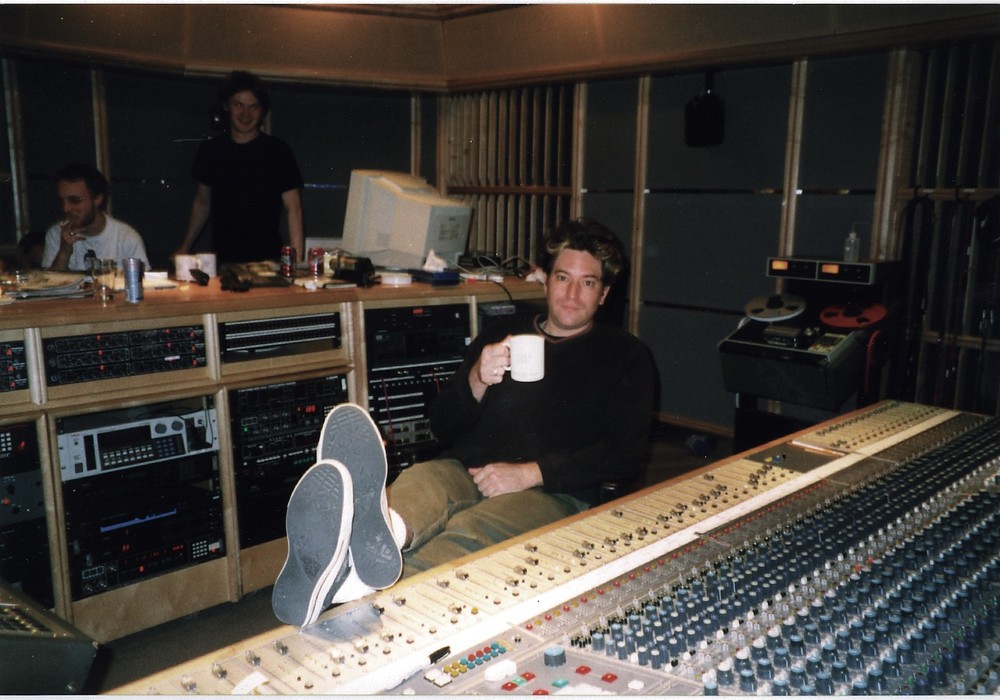

If the mark of a great recording studio is the versatility and breadth of its clientele, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better candidate than Richmond, Virginia’s Sound of Music. John Morand, the studio’s co-owner, producer, engineer, and a recording artist, has, over the past three decades, presided over sessions for artists as disparate as Hanson, Gwar, Joan Osborne, Lamb of God, Sparklehorse, and Clutch. John’s sanguine disposition and spacy good humor somewhat belies the studio veteran’s expertise with every facet of the recording studio, including video recording and editing. His enthusiasm in the studio is infectious: He remains the only engineer I’ve ever worked with who I’ve spotted, on multiple occasions, dancing with abandon around the control room as the band is recording. I spoke with John amidst scaffolding and piles of lumber, as he prepared for his studio’s ninth – and, he insists, final – relocation.

What got you interested in recording?

My dad worked for a big advertising agency in Chicago. He worked on campaigns like the Jolly Green Giant, the [Sugar Smacks] Dig’em frog, and the Pillsbury Doughboy. When I graduated from high school, I went to work for him at his audio-visual production company/ad agency, where they were making industrial corporate videos. This was before video was such a thing, so they used to use slides and even film. I did the sound parts of that, putting in the narration, editing the music, mixing it together, and balancing it. We had a very small recording studio in the basement of the office for recording voiceovers. I did my very first records there.

What setup did you have?

Originally, it was just a 4-track reel-to-reel and a Quad Eight mixing board, but then we moved to another building, built a bigger studio, and got an Otari 8-track. That’s when I recorded the first Honor Role albums, as well as some of the avant-garde bands from Richmond. I would work all day on commercials, and at night bands would come and we’d record music. Then my dad’s company merged with a bigger company and they wanted to move the whole studio to New Jersey. I had to decide, “Do I want to keep doing this, or do I want to make records?” Since I didn’t go to college, I was thrust into the world of adults, working with people in their 40s and 50s in advertising. I was living in that world, but I also missed a lot; I wasn’t playing in a band, I didn’t have a girlfriend, I wasn’t hanging out in the park with college kids skateboarding. So, when my dad sold the business, I started doing live sound here in Richmond, and working in other people’s studios for bands like Red Hot Chili Peppers, Meat Puppets, and The Pixies.

You never had any formal training? It was all hands-on?

Well, I trained at a local studio here called Alpha Audio, and it was the only 24-track studio between [Washington] D.C. and Atlanta, [Georgia]. It opened in 1972, and it was designed by Joe Tarsia [Tape Op #68] from Sigma Sound [Studios] in Philadelphia. They taught recording classes there, so I was lucky enough to learn hands-on in a real recording studio, with a Studer 24-track. That was my model for what a studio should be; that place was legendary. I learned so much from being there.

How did you hook up with [Sound of Music co-founder] David Lowery?

David’s band, Camper Van Beethoven, had broken up on tour in Europe, so he and Johnny [Hickman, guitar] moved to Richmond. Cracker didn’t have their record deal yet, but David still had the key man clause with Virgin [Records], so he moved here and started writing songs. Virgin signed Cracker, and they went to California and made the record [Cracker]. When Cracker was on tour in Europe, David met this band from Germany called F.S.K. who asked David to produce their record. When they were ready to come to the States to do the album [Son of Kraut], David was in a grocery store in Richmond; the store was selling these cassettes at the counter, including one by this band I had recorded called Plate. David bought the cassette, listened, and thought it sounded good. So, he called me up. F.S.K. then came to Richmond to do a 15-day session, which was the longest I’d ever spent on a record by that point.

You were more accustomed to knocking sessions out in a day or two?

Yeah, I was used to that because no one had any money to record. F.S.K. were so cool. They were from Germany, were super intellectual, and they played this weird, avant-garde country music. [Singer/songwriter] Michael Hurley came in and played on a song, because we were huge fans of his and he lived in Richmond at the time. When F.S.K. came back to do a second record [The Sound of Music], we rented a studio, then started renting it month by month, and that eventually became Sound of Music. The second Cracker record [Kerosene Hat] came...