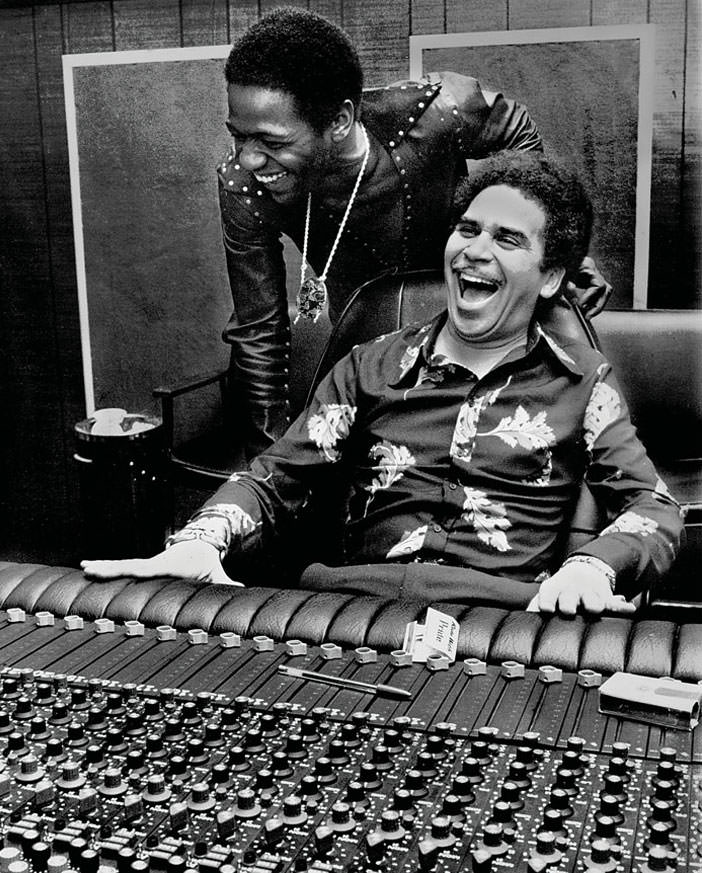

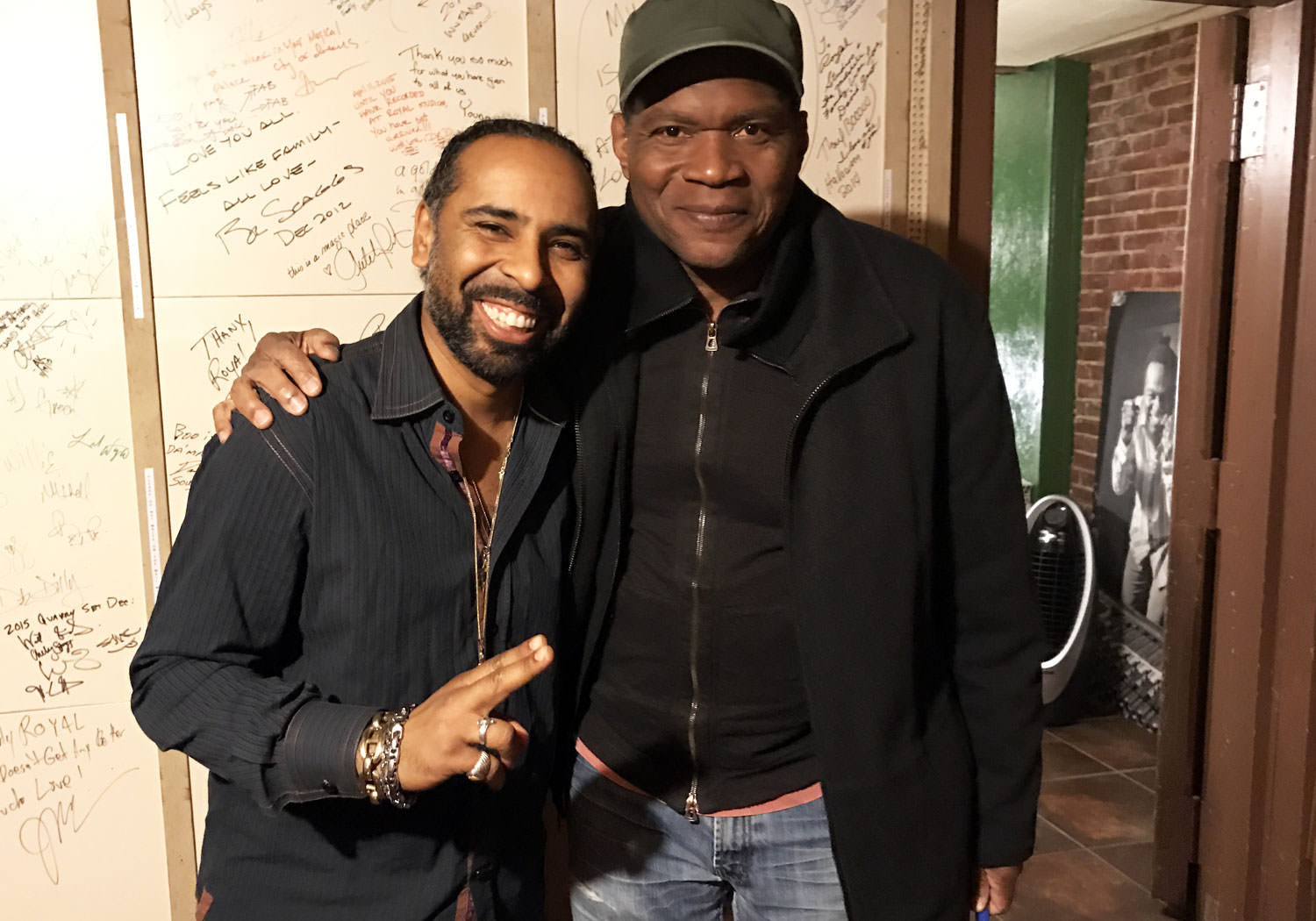

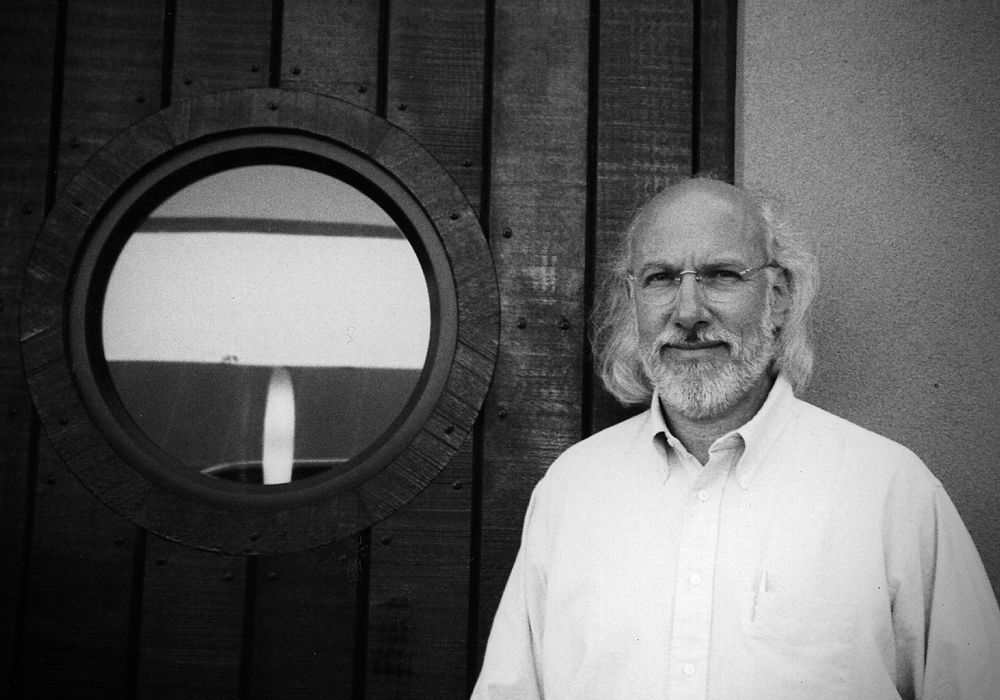

Famed producer, musician, and arranger Willie Mitchell became involved with Royal Studios (and the associated Hi Records) in Memphis, Tennessee, in the early ‘60s. He took more control of the studio operations as time went on and, in the early ‘70s, his collaboration with singer Al Green led to millions of albums sold, all of which cemented Willie’s reputation as a producer of note. These days his son, Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell, a musician, songwriter, engineer, and producer in his own right, runs Royal Studios and co-owns Royal Records. He keeps the legacy alive, while also looking to the future. Boo’s produced and/or engineered a wide range of acts including Melissa Etheridge, Solomon Burke, Al Green, Cody Chesnutt, Rod Stewart, John Mayer, Snoop Dogg, Bobby Rush, William Bell, Keb Mo, Terrence Howard, and Boz Scaggs. I met up with Boo one evening at Royal Studios (currently celebrating their 60th year) in the back control room to discuss his life in the studio. Later that night we went out to Beale Street, ran into Leroy Hodges at a club, danced to a live cover version of “Uptown Funk,” and maybe had a few too many drinks. In other words, a pretty awesome night in Memphis.

Your dad was producing records as you grew up. What are your first early memories of that?

I remember coming to the studio when I was real small. Probably four or five. He’d been here since almost the beginning, since like ‘58 or ‘59. When Elvis Presley left Sun in ‘55, Elvis’ bass player, Bill Black, was trying to do his own thing. There were another couple of guys at Sun. One was the engineer Ray Harris, and the other was a producer, Quinton Claunch. They were trying to do their own thing with Bill. They got the guy who owned Poplar Tunes Record Shop, Joe Cuoghi, to buy this place [Royal]. That’s where Hi Records comes from. Cuoghi owned all the jukeboxes in town. Any time you saw Elvis in a record shop in the ‘50s, it was at Pop Tunes. Pop [Willie Mitchell] became probably the second or third artist signed to Hi. Joe Cuoghi died in ‘70. He left in his will for my dad to take over the operations of Hi Records. I was born in ‘71, so it was always his place to me. The other owners were never here. I don’t think they had offices here. They had offices in Pop Tunes, and my dad even had offices in Pop Tunes. I started coming in when I was like four or five, and I’d really be after the Coke machine! But every time I came down here, I always felt like there was something enchanted about it. I think by about the time I was nine, I started coming down here with Pop on the weekends, spending my summers down here watching him.

Were you helping?

Yeah, just whatever little simple tasks that a nine-year old could do. Mostly just watching him. I played keys. It must have been ‘80 or something, and all the cool Moogs were out, and the [Roland] Juno. I just wanted to be in the studio all the time. Watching the guys play, you know!

Did Willie keep a pretty straight schedule here, or was he doing late nights?

We’d stop and get breakfast, get here around ten or eleven, and then stay until we got it done. He was always working; always doing something. He would go to other studios, too. He would kind of break bread. I remember going to this place called Shoe Studios & Productions, over on Broad. It was Warren Wagner’s studio. I remember going there as a kid, but I didn’t really know why until after my dad passed away. I got this nice letter from Warren saying, “Your dad cut this Christmas album at my studio because we were having a hard time.” Pop got some label who had given him a deal to cut this Christmas record. He was like, “Man, if ya’ll are struggling, I’ll just cut it over there.”

When he could have been here? That’s pretty generous.

Yeah. He was just that type of dude.

Were you playing in bands when you were young?

No, I was just playing on my own. I think I probably wrote my first song when I was about 14. I started rapping when I was 16. That was around the time that Pop first bought us [Boo and Archie, Boo’s brother] a Tascam 4-track cassette recorder. By the time I was 17, he bought us a Fostex 8-track cassette. We thought we were slicker than goose shit.

It’s like, “Here you go. Here’s a 4-track. Learn on your own.”

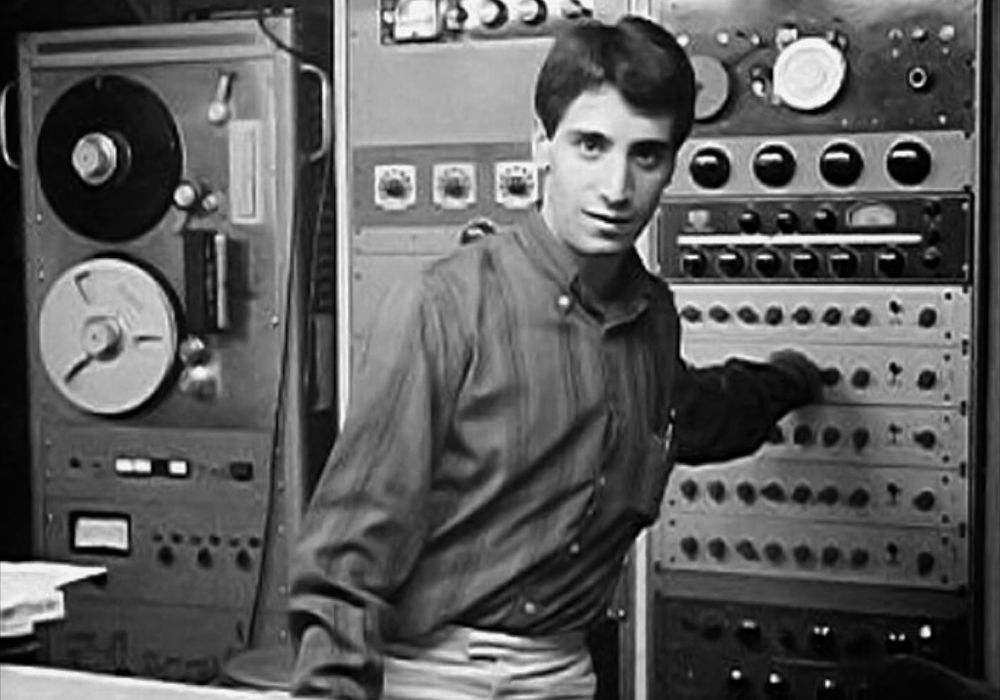

Yeah. It was amazing. We started to cut all this music. That’s when I started working on my rap album, when I was 17, and when I started messing with the big boards and gear. We moved back here [to the rear control room] in ‘89. The last record we had cut upstairs was Keith Richards’ Talk Is Cheap album. This place was bought in ‘56 and turned into a studio in ‘57. So from ‘57 to about ‘73, the main control room was here, with those big, green [Altec Lansing] Voice of the Theatre speakers. The actual ones that he mixed all the Al Green songs on are back in the preproduction room by the bathroom. All of his equipment was in here, the old 8-track decks and gear. Then, whenever quadrophonic came out, and 16-track, they moved the studio upstairs.

I’ve never been upstairs! We’ll have to go up there later.

All my memories were mostly from upstairs.

Were both studios running at the same time?

Probably only for about a year. I think by ‘74 or ‘75 everything had transitioned to being done up there, and this room was collecting dust. In ‘89, right after we cut that Keith record, gear was changing. I think we had the 24-track tape machine by ‘87, but he put it upstairs and said, “We’re going to need a bigger board.” When we came back down here, that’s when I got my hands on gear. I was here helping them build the room out. I remember the whole process. Even putting this board in. This board [MCI JH-536C] came from Compass Point Studios [Nassau, Bahamas]. I think what sold my dad on the board was Randy Blevins [Blevins Audio], in Nashville, who said, “Man, they cut some Stones records on that board.” My dad was like, “Yeah, I just did Keith’s new record. Let me check it out!”

That’s funny.

Even when they were installing the board, because the time transition was only months, Keith was calling my dad trying to get him to come master the record with him. Pop said, “Keith, man, I can’t come! I’m trying to get my studio up. I told you, I can’t come! I can’t do this.”

Your dad was a producer. Was he an engineer?

He was. He stopped the older he got. When he got here, his first contract was with this company called Home of the Blues Records in ‘59. Ruben Cherry owned it. The store was on Beale Street, but they cut their records here. Ray Harris was the engineer from Sun, and my dad never liked the way his records sounded. Ray told my dad, “Black people can’t touch the board.”

Wow.

Yeah. Pop was like, “Okay, whatever…” He had left Home of the Blues, and Joe Cuoghi signed him to Hi Records. The first two Willie Mitchell records didn’t have his picture on it. Ray and the other guy said, “Well, you know, you can’t put a black dude on there. Just put a nice white lady on it and everybody will buy the record.”

Oh, yeah. I’ve seen some of those covers.

This A&R guy, Dickie Klein from New York, was the promotion man for London Records; the distributor for Hi Records. He told them, “If Willie’s picture is not on the next record, I’m not working another Hi Record.” He was a really good friend of my dad’s. Hi Records had a Jumpin’ Gene Simmons “Haunted House” single that was a million seller, and Dickie had broken that record. So Dickie had a meeting with Joe Cuoghi. He was looking to Ray, Quinton, and others to tell him what to do with the record company, because he hadn’t ever run a label before. It was like, “Okay, put Willie’s picture on the next record.” In ’59 Bill Black had this record called “Smokie, Part 2”, which was his biggest record. But it was a Willie Mitchell record.

Oh, really?

It was Pop’s record with Pop’s band; the record was so good, and Bill was so big an artist that they put Bill Black’s name on it. Pop was pissed, man! Joe Cuoghi said, “You’re just ahead of your time.” I think it was sometime around ‘64 that Ray Harris sent somebody to get something out of his car. The guy opens his trunk up, and there’s this fucking KKK outfit in his trunk. One of the black musicians was walking by, saw it, and knew. He was like, “What the fuck?” Pop had a meeting with Joe about Ray, like, “What are we going to do about Ray?” Joe said, “I don’t know.” Pop replied, “Let me buy him out.” So Pop bought Ray out. Pop told him, “Ray, I learned a lot from you.” Ray said, “What’s that?” Pop said, “Never cut a record like you cut it.”

What not to do!

Yeah. The studio looks the way that it looks because my dad never liked the way his records sounded. He would always complain and say, “You can’t tell the difference between a Willie Mitchell record and an Ace Cannon record.” Once he got Ray out, he started experimenting with Bill Cantrell, the guy who built probably most of the studios in Memphis. They started experimenting with putting in insulation and burlap until he got the sound he wanted. You can listen to Willie Mitchell instrumentals in order, and you can hear the sound dialing into the Al Green sound. If you listen to Willie’s “20-75” [1964] and then “Soul Serenade,” which was tracked in ‘67, you can hear the sound – everything’s getting quieter.

Drier and more focused. I always tell people you can have a jazz number playing in a room, and it sounds roomy and in a space, and then you can have Al Green’s snare; this big, thick, deep sound right in your face going “thwoomp.” They’re both completely valid.

Exactly. It’s just what you want at the time. All of that design is his doing. He got it like he wanted it by ‘69, when he perfected it. He had his all tube, 8-track tape machine. I think [Al Green’s] “Tired of Being Alone” was the first record that has the perfected sound. You can even listen to other Al Green records, like “I Can’t Get Next to You,” and the sound is different. But when “Tired of Being Alone” comes on, it’s like, “Oh, shit!” That’s it, right there.

You’re talking about an era when studios and regions were known for a sound.

Yeah. And most places were going the opposite direction. But Pop, everything he did – even when he would be working on a record, or producing it – he wouldn’t listen to the radio, because he didn’t want to unconsciously steal. That’s where I learned most of my engineering; from him. It was only when I got older and smart enough to say, “Hey, how did you do that?” When I first got into this, me and my brother Archie were doing rap. My brother was always of the mindset that we need the same gear that other studios have. There was this big argument about JBL speakers and this board. Pop said, “We don’t need any fucking JBL speakers.”

You can still make a good record!

Yeah. It was just a little argument and I was finally thinking, “He’s got more gold records than we’ve got. He knows what he’s talking about.”

You’re young, and you have to rebel.

Yeah. I had my rap career from ‘87 to about ‘93. Then we opened a club on Beale Street; Willie Mitchell’s Rhythm N Blues Club. I started out as busboy, then I was a waiter, then I was a bouncer for most of the time, then I was a bartender, and then a manager. I was also getting people to come in and perform. We did an Al Green concert, Bobby Rush, Johnnie Taylor, and Michael McDonald even sat in a couple of times.

Is that venue still open?

It’s a Coyote Ugly now. I was at the club most of the time, and then I’d come to the studio after I would get off at like three in the morning. I produced a record on this Japanese artist and Pop ended up producing the rest of the guy. The guy liked a demo, or something I did, and wanted me to produce his record, so I wrote one song. Then it got too big, and Pop ended up producing the rest of it. There are people like JVC [Records] calling, and I didn’t know what to do! When we got rid of the club in ‘98, and I came back to the studio, but I was helping people copyright their songs. I thought I wanted to be a lawyer for one split second of my life, so I started reading up on all the music law, as well as trying to find out about copyright law. I knew enough to be dangerous. I would help guys set up their publishing companies through BMI. I was kind of managing the studios. Like, “Fuck, man, we don’t have a logo? We should have a logo!” We’d had “Royal” out on the building since 1939, but this isn’t Royal Theater.

That’s right, it comes from the former theater that was here!

It started out as the Shamrock Theater in 1915, and then, I think by ‘39, it became the Royal Theater and stayed that. I would still produce some R&B projects that I liked, as well as some rap. I made tracks too, but I never really liked making tracks. If I was in the mood, I would do one. But if somebody hired me to do one, I never really liked that, for some reason.

Your brother Archie was doing projects in here too, right?

Yeah. He was making most of their tracks. We also had William Brown. William Brown started engineering for my dad in like ‘86, I think.

He had a long history with Stax, didn’t he?

Yeah. William was from The Mad Lads, and William engineered all The Bar-Kays hits of the ‘80s, like “Freakshow on the Dance Floor.” William was like this wizard dude that had the ‘80s sounds down, as well as a little bit of the ‘70s, like cutting tape. When we started doing our rap music, William was engineering a lot of it. We’d do remixes on 1/4-inch, cutting tape up. William had a stroke at the beginning of 2001, and Pop still let him work for a few months, but it just got to where he couldn’t really talk.

He would have been an amazing interview.

Oh, my god. That dude had stories. My brother Archie started engineering at the end of 2001. He became the head engineer, and I was just doing most of the business. When Al Green got the deal with Blue Note Records for I Can’t Stop, I was the project manager; trying to figure out what union scale was, and all that.

That was a nice comeback. It gave Willie a lot of acclaim too, because people realized that was the combination of these two guys that had made those hits in the past.

Yeah. They really wrote some cool songs. I was there for all of that. My dad had some health issues too, around 2000. He’d been in and out of the hospital. I always loved him and looked up to him, but me and him started getting really cool around ‘99 or 2000. He wasn’t driving anymore; I would pick him up and take him to work every day, and take him home at night. They put out a “Best of Willie Mitchell” record, and I was like, “Damn, Pop has some dope-ass instrumentals.” We’d listen, and it would be songs he’d even forgot about. I started picking his brain, and asking about who’s playing the solo. He said, “Oh, that’s Fred Ford on that song.” I said, “Fred Ford? Really? Who wasn’t in your band?”

At some point, everybody!

Yeah. He was like my best friend. I just started asking him questions. By 2004, they had done another Al Green record called Everything’s OK. It must have been in the fall of 2004, they were trying to put the record out, but they wanted “You Are So Beautiful” and Blue Note wanted it remixed. My brother had kind of disappeared. He was off; I think he went out of town and didn’t really say anything. Pop didn’t know that he had gone on vacation, and he was sitting there pissed off at the front desk. He goes, “Man, we gotta remix this record and your brother’s on vacation!” I said, “It’s not a big deal. I know how to engineer, and you have the best ears, so why don’t me and you go back there and mix it?” We went back here; I was scared shitless. I’m like, “What have I got myself into?”

“Now I’ve got to do a good job.”

“This is an Al Green record!” Blue Note loved it. From that moment, it was the first time that we’d actually worked together. The other times would be me back here, mixing somebody’s project and everything sounded like shit. I’d go up front and get him, “Pop, come back here. I don’t know what...” He’d come back and turn two little knobs, and it sounded like somebody pulled a blanket off the mix. It always fascinated me. “How did you do that?” I’d cut some rap, R&B, and gospel on the side, and he would always bail my ass out. But this was the first time that we actually sat down and did something together. From that moment on, I became his head engineer. The next thing we did was John Mayer’s Continuum. We didn’t have Pro Tools. Before this, I’d wanted to master. I looked to see what kind of PC could run Pro Tools. I found something on a Pro Tools message board, and I built a PC computer. I put Windows on it, and I had this little MOTU 24 I/O – that computer still runs now, with a single core processor. So when John Mayer came in, I recorded everything to tape and backed it up into Windows. After that it was then Buddy Guy. Steve Jordan was the producer on a lot of this, and they had Pop doing horn arrangements. The Buddy Guy interaction with my dad was hilarious. Don Smith? He passed away. Wow, what a dude. Absolutely out of his mind, but he was a genius. He was engineering Buddy Guy, and I was assisting. So when it came time to do the horns, it was like, “Okay Boo, how do you do horns?” Buddy and Pop would be having this OG conversation. Two masters, who have been through everything.

I can imagine.

So my friend, Craig Brewer, was working on this movie called Hustle & Flow all during that time, and he came by to say “Hi” to Buddy Guy. He and Buddy were talking, and Buddy goes, “Man, I haven’t been to a movie since that movie about the...” He goes, “Hey, Willie? What’s that movie about the fish?” Then Pop’s down the hall yelling, “Jaws!”

That’s insane. Craig must’ve been scratching his head.

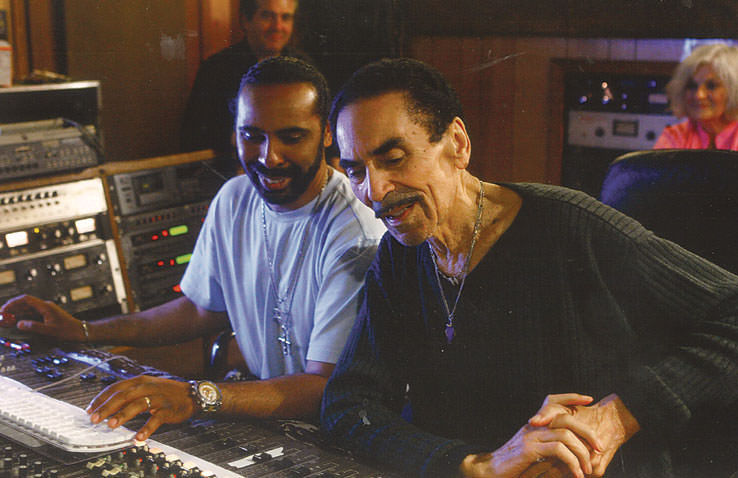

It’s like, “What? What the fuck?” In 2007 I was picking Pop’s brain about everything I should have been asking him 20 years before, when I was talking about the JBL speakers. So Solomon Burke calls. The last time I saw Solomon was during the Stax 50th Anniversary Show at the Orpheum. I was dropping off some checks from a session and I ended up being trapped backstage with Solomon. I wasn’t even planning on going to the show. We’d talked about him and Pop cutting, but Solomon was signed to somebody, so it didn’t happen. Then, in 2008, the phone rings, and it’s Solomon. He said, “Hey, Boo? Man, we’re coming through there. Would you get your dad and some musicians together? We’re going to cut some stuff.” I said, “Okay. Pop, Solomon wants to come, but we don’t have any songs.” I just called all these badass musicians, like Lester Snell [keys], Steve Potts [drums], and Dave Smith [bass]; all these dudes. I’m like, “Man, just be here at six. I don’t really know what we’re gonna do.”

Oh, my god.

Solomon came through, wrote some, and stayed a couple of days. We got some cool songs out of it. Then, after that initial little contact, they spent about another month trying to figure out how to come back and do it proper. Pop and Solomon went in on the thing; we started cutting this amazing record that ended up being basically my graduation record. All the way up until then, even going back in the day, I would always wonder, “Man, what am I going to do if something ever happens to Pop? What if he’s not here to bail my ass out?” I wasn’t depending on him like a crutch, but he was my cushion and my support. He could tell that I’d always be trying to do work that would be pleasing in his eyes. It was during the mixing of that Solomon record when he looked at me and said, “Man, when you’re mixing, don’t try to please me. I’m the only motherfucker in the world that can please me. You can’t please me. You’ve got to please you.” This lightbulb went off. He was basically telling me, “You’ve got to do what sounds good to you. You’ve got this.” We mixed that record, like three or four songs a day. I had never mixed anything that fast. At that moment, I thought, “Okay, I think I might be able to do this.” But I still wasn’t sure. I wasn’t so worried about it after that. He was trying to get me to trust myself. That was a profound moment in my engineering career. You can “what if” anything. With the snare drum, you could nitpick it, but at some point you have to make a decision and trust yourself.

So true.

Then Pop broke his hip. We didn’t even know it. We just came in one day and he said, “Man, I fell.” I said, “Let’s get you to the hospital.” He said, “No, man. Just sit me up on the couch.” That went on for a couple of weeks until I said, “Dude, you need to go to the doctor.” We went, but he had diabetes, and it kind of snowballed. In the midst of all that, Rod Stewart wanted some arrangements. Pop’s in a wheelchair, he wrote them, we cut them, and then he went right back into the hospital. It all got worse after that.

Yeah. Sad days. Were people realizing that you were able to take on the reins, or was it kind of hard?

No, it was hard. All you know is what you feel. I was feeling like the word on the street was probably, “Willie’s done all this, but we don’t know what the fuck he’s doing.” That’s normal. I get that.

He had a lot more years on you.

Yeah. There were a few people, like this dude from Spain that wanted my dad to do this record. He said, “Well, me and you will do it.” We did a record [Jus’ Blue] for this lady, Barbara Blue, who’s been singing on Beale Street for 20-something years. She has a real big voice. These people had talked to Pop about doing records, and they trusted me to do them. I was working on Deering & Down’s record [Out There Somewhere] during that time, but then Pop passed. The first real major break was Cody Dickinson [of North Mississippi Allstars].

Oh, yeah.

Pop had been passed away for about a year, and this was right at the end of 2011. Cody calls me, and he starts telling me about this Take Me to the River project. If you say the D-word, the “documentary” word in Memphis, you clear the room. All the major, older musicians will just scatter, because there have been so many documentaries made, and everybody got fucked. Nobody got anything, and whoever made it got all the dough. Everybody had a bad taste in their mouth about documentaries. So Cody’s telling me about Martin Shore and this Take Me to the River film. What he wanted to do was put older musicians with younger musicians, and play music in Memphis and the Mississippi Delta. He said, “Boo, he’s trying to do the right thing.” It just resonated. I met Martin, and we hit it off instantly. He wasn’t trying to screw anybody over. All of his cards were on the table. During that call with Cody, I said, “Who do you want to produce it?” Cody said, “I want you to produce it.” So the next thing I know, I’m recording William Bell, Kirk Whalum, Snoop Dogg, Bobby Rush, Frayser Boy, Otis Clay, and Terrence Howard. That was 2012; a good, heavy year. I always say that Solomon Burke opened the floodgates to Royal and blessed us.

Was Solomon Burke’s Nothing’s Impossible Willie’s final record?

Yeah. From Al Green’s last record, from about 2005, times were weird for studios everywhere. There were a lot going out of business, and the economy was all screwed up. When Solomon came in, people started to want to come to Royal again. After Take me to the River, next thing I was doing was Wu-Tang Clan’s record [A Better Tomorrow], and then Boz Scaggs [Memphis]. Steve Jordan normally only did overdubs here, like horns, strings, keys, vocals, or whatever. But Steve called and said, “We’re coming down there, and we’re going to track.”

You’ve got to be ready.

He brought Niko [Bolas] with him. Every time I work with some other badass dude, I think my engineering skills do like the Intel chip – they split, and I become twice as good instantly. The only way you’re going to get better is to work with motherfuckers who are better. Niko was my confirmation. Niko and Steve asked, “How did Willie get the ‘Al Green’ drum sound?” It was funny, because I knew it, but I had never done it. It was the first record where I was like, “Damn, that works.” A lot of people try to study it… Three mics, damn. So I started incorporating that. At Royal, textbook shit just doesn’t work.

Because of the sound of the room?

Yeah. We got to do the strings, so I started to mic the strings. Niko’s going, “What in the fuck are you doing?” I said, “I’m mic’ing the strings!” He just shook his head and said, “Okay.” So they start playing, and he said, “Holy shit.” He called Al Schmitt and was like, “Al, you’re not going to believe this.”

What’s different in your technique here?

It’s just mic placement and selection. There’s no Decca Tree! I’ve even altered my style lately to be more like Pop, with one microphone on the strings. Even horns too. During the William Brown era, music was getting “modern,” and Pop wasn’t using a lot of his OG techniques that he’d used in the ‘70s. He was letting William do his thing. I had come from that, because I learned a lot from William Brown, initially. The ‘80s kind of engineering, where you’re EQing everything and all that, that’s how I learned. It always sucked to me. Then I had the little voice, “Try it with no EQ!” I thought, “Whoa, that sounds better!” I used to try to gate my tracks. I remember when Pop was saving my ass on a mix one time. He said, “Man, take all that off the toms. You get some of your drum sound from the tom mic. You’ve got some snare in that.” That’s why all the gates are in the hallway, and they’ve been there since 2005.

Just put them away.

Yeah. What I’ve learned on my own has been implementing what Pop did, as well as using his methods and approach. How does it sound? Who gives a shit if it “looks” wrong or is textbook wrong. What does it sound like? What does it feel like?

That’s always so much more important.

He was like, “We’re not selling music. We’re selling feelings. Don’t be caught up, like if some instrument is out of tune, or there are some mistakes. How does it make you feel?” He said, “If you’ve got a hit record, you can cut it in the bathroom on a cassette.”

It’s enough.

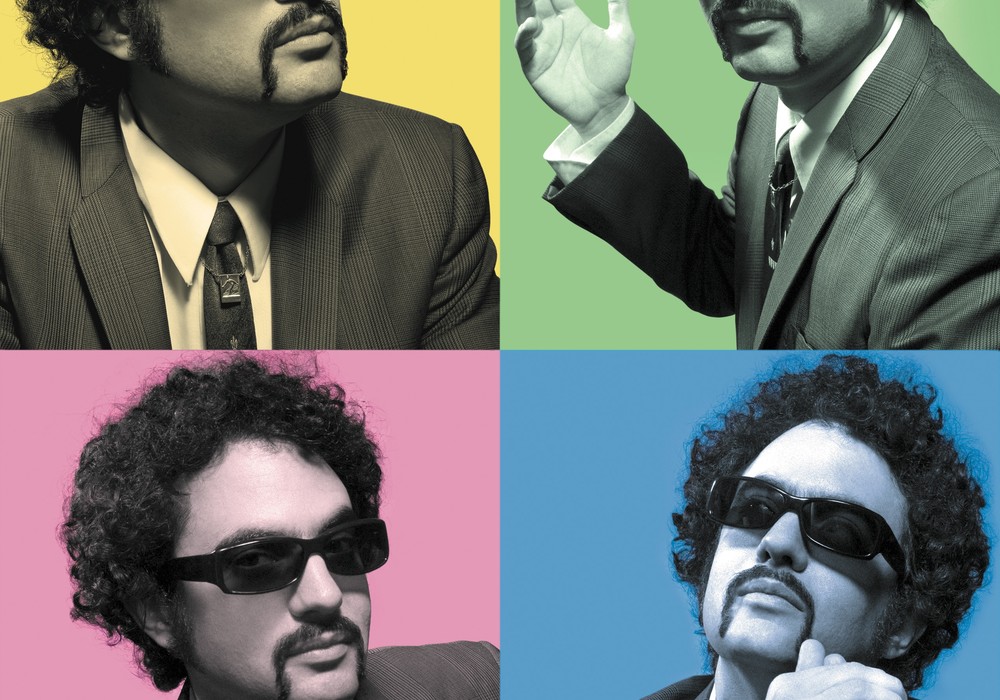

Really. When I was working with Mark [Ronson, Tape Op #105] doing the “Uptown Funk” vocal, we had Bruno [Mars] in the vocal booth, and all of us, like me, Kameron Whalum [his trombone player], Mark Ronson, [co-producer/writer] Jeff Bhasker, and [co-writer] Philip Lawrence were all in here [the control room] jamming. Bruno’s like, “I want to come in there with you.” With Bobby “Blue” Bland, one of his last recordings we did with him on a [Shure SM]57 in here with somebody telling him the word right before he was supposed to sing it. That’s the only thing I could think of. “He wants to do a vocal in the control room? SM57!” It was five in the morning and Bruno had an eight o’clock flight. We’ve got to get this. So he does a couple in here, kills it, and everybody is having fun. I just know they’re going to replace this track. I get a call a couple weeks later from Charles [Moniz], Bruno’s engineer, and he’s like, “Man, you know that vocal we did in the control room on the 57? We’re keeping that.” I said, “What?” Cheapest mic in the building!

And it worked.

That is what is going to get the performance. You’re trying to capture the magic, man. That’s what was needed to put him in the zone.

That record went nuts. Was Mark and Jeff coming down here to work on that with you a turning point for revitalizing Royal too?

Yeah, that was another. Working with Steve Jordan on the Boz Scaggs record, I was like, “Oh, I’m about to implement some of this Willie/Al Green mic’ing.” My drum sound went from okay to like a motherfucker, overnight. I did Wu-Tang Clan after that, and they sounded like they were using my rough mixes!

They keep it raw.

So that helped. All my recordings started sounding way better, implementing a little bit of the OG mic’ing. “Uptown Funk,” yeah, it changed my life. It’s so weird how this happens. I had been going through a lot of family shit, and those dudes came right when I was feeling like, “I’m doing the best I can. Am I doing something wrong?” It’s so ironic, because they came through looking for singers, and I didn’t really know who they were. I knew their work, but when this person was telling me about them, I didn’t. I wasn’t catching the names. I was like, “How do you spell that?” I was trying to Google them!

Someone mentioned Jeff Bhasker’s name to me the other day and I thought they said Jeff Baxter. Not The Doobie Brothers’ guy!

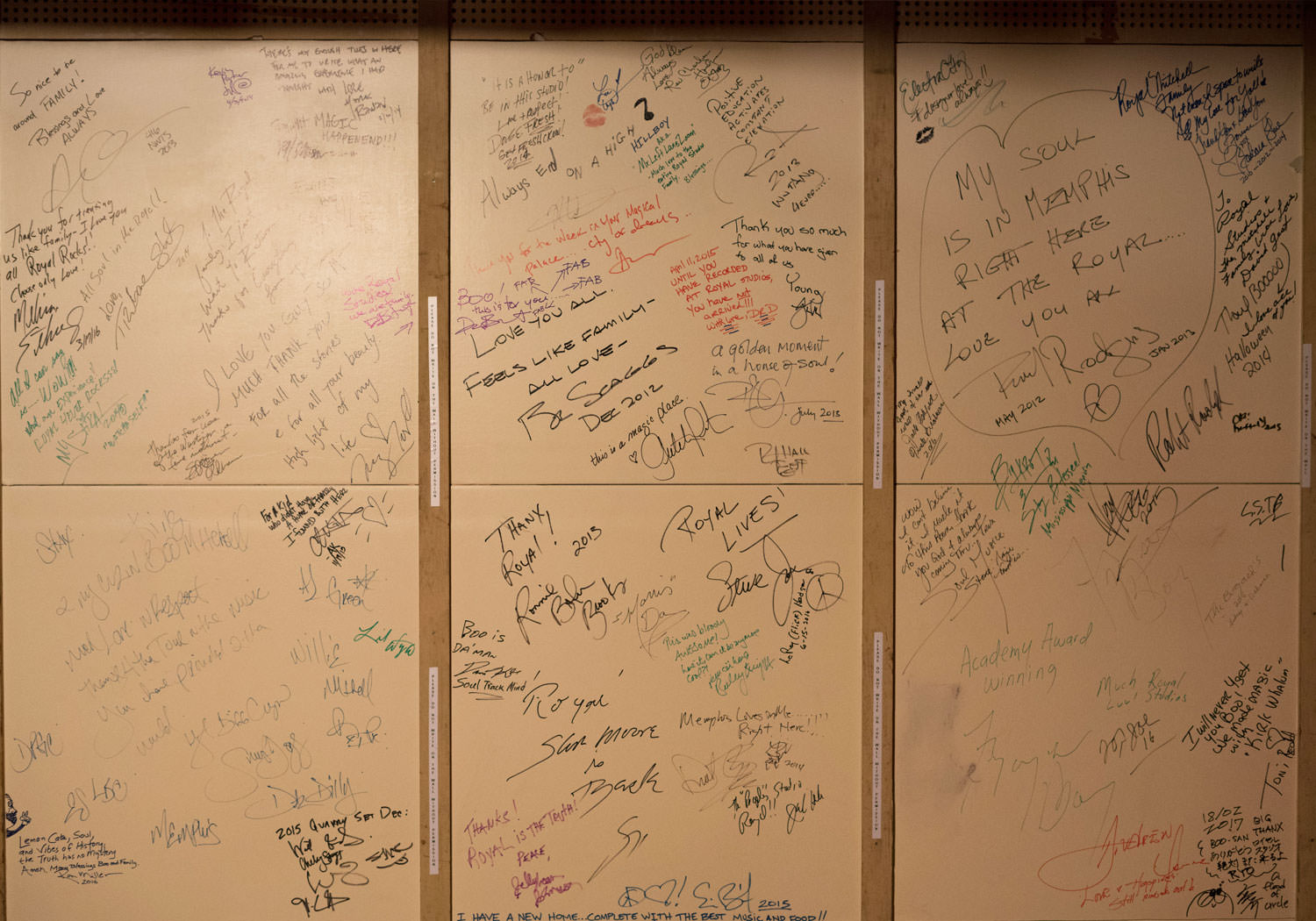

I got called about the sessions, about them coming through looking for singers. They came in and really freaked out about the studio for about an hour. I remember Mark coming in here and saying, “Oh, I know that desk! I have one of those! Your dad had one of those, so I bought one.” After they listened to people sing, Mark said, “Hey, I want to make my album here.” I had gotten their names right by that time, and Googled them, and I was like, “These guys are two of the heaviest fucking dudes in the music industry!” Mark’s agent called the next day and said, “We want to come in for ten or eleven days.” I already had another session booked, and the guy had paid me a deposit. It was a local, famous Memphis songwriter and he had some guys coming in from out of town. I didn’t know what Mark was doing, but I had the feeling like, “I know this is going to change my life.” I don’t know why. I had to call the Memphis dude and say, “Man, I’ve got to move your session.” He was like, “I’ve got people coming.” I said, “I will give you free studio time. There’s something about this session; I know I’ve got to do it.” He ended up doing it at another studio, and I gave him his deposit back. Mark showed up a week later with Steve Jordan [drums], Willie Weeks [bass], Emile Haynie [co-writer], Kevin Parker [Tame Impala, Tape Op #95], Homer Steinweiss [drums], and Trombone Shorty [trumpet/trombone].

What are they all doing in the same room?

And this Pulitzer Prize winning author, Michael Chabon, who insisted on walking the neighborhood. He said, “Oh, it’s a lovely neighborhood. I was at the Sons of Light Motorcycle Club.” Mark was so cool. About day seven, Mark’s said, “Hey, man; I’ve got this song I want Bruno to come here and record. Let me play it for you.” I said, “Mars?” He played the “Uptown Funk” demo, and I was like, “Oh, that’s going to be pretty cool.” They flew Bruno in; the song wasn’t even finished being written. They had a verse and part of the chorus, but they actually wrote the rest of the song in the hallway here.

Last minute?

Yeah. It was surreal. At four in the morning, they’re out of booze, and it’s like, “We need some booze.” I go and look in my dad’s office, and next to his Grammy is a bottle of this small batch of Four Roses bourbon, signed by the master distiller. I just looked at it, and it was another one of those moments that’s like, “Damn, I’m going to have to take one for the team.” I’m pouring it in Bruno’s cup, and he goes, “Yeah, Boo! Fill my cup! Put some liquor in it!” About 30 minutes later that ended up in “Uptown Funk.” Bruno was here for three days. They wrote another song [“Feel Right”] with Mystikal while they were here, and we tracked that. All the women in my family are singing background on it.

That’s hilarious, man!

Yeah. Bruno’s playing drums on it.

What happened after that?

The record came out. I remember the first time I heard it on the radio thinking, “Damn, it’s too long. They’re not going to play it again.” They hadn’t edited it, at that point. It was four and a half minutes, or something. That was November, and by January, man! I remember somebody emailing me and saying, “Your record’s number one.” Then it started going nuts. I looked it up; Memphis hadn’t had a record on the [Billboard] HOT100 number one since [Rick Dees’] “Disco Duck.”

That’s a weird fact.

Yeah. It started getting stupid: 12 weeks, 13 weeks in the charts. All of a sudden people are calling me. I’m on magazines in Memphis. Then the whole Grammy thing started happening. When the nominations came up, I remember checking the website and I was like, “There’s my name. What does that mean? Am I nominated?” The night of the Grammys, Hal Lansky [Lansky Bros.] hooked me up with clothes before I went. He said, “You’re going to the Grammys. Come on!” He used to do my dad’s clothes, as well as Elvis and Al Green. I went and got Lansky’d up. I had all my Lansky that I was going to wear, the jacket and whatnot. I thought, “I think I’m going to wear my dad’s leather jacket.” From my childhood, that was a jacket he’d worn all the time when I was growing up. He’d given it to me in 2007. I never wore it. I didn’t know if we were going on stage or not. I thought, “I don’t work for any of these guys. I don’t know what y’all are going to do, but if I hear ‘Boo Mitchell,’ my ass is going on stage.” It was just an awesome moment. I felt like it was a “Willie Mitchell victory.” And I felt like it was kind of a Memphis victory, you know what I mean?

For sure.

That’s what made me the most proud, and happy. Pop fought all the people that talked shit about our little studio and didn’t think we could do anything meaningful. In the ‘90s I used to be mad that people weren’t calling my dad to work.

Just because someone’s not on the charts at the moment doesn’t mean they don’t have all the skills to help you make records. It’s a fickle industry.

Yeah, exactly. That’s another cool thing about Mark. I guess he grew up in a similar situation as me. He has a lot of respect for the past, as well as older musicians. He’d bring Carlos Alomar down here to do a guitar part. I’m like, “Mark, your part here is dope.” He’d say, “Nope, I’m going to get Carlos to play.” [Guitarist] “Teenie” Hodges is on the album. That was the last record Teenie played on. I’m all about the future, but if we still have these treasures it’s just ridiculous to not have these guys. Like, Charles and Leroy Hodges [keys and bass], from the Hi Rhythm Section. They played on 26 gold and platinum records in a row! That wasn’t an accident! If you get them in the studio, something is going to happen. I work with some young musicians, but I don’t do anything without having one of those dudes present. Most of the time it’s all of them, coming full circle to this Melissa Etheridge record [Memphis Rock and Soul].

I was going to say, that’s a great example of this.

Man, John Burke [co-producer] is just awesome, but that’s the first record with a major artist where they let me pick all the players, as well as 100 percent of the engineering. “Do your thing,” you know? I’m like, “Okay. If I was cutting it, then I would get Charles Hodges, Leroy Hodges, Archie ‘Hubby’ Turner [keys]...”

Man, that’s a treat.

That record is my latest transition to, “Hey, this is me.”

You did all the engineering, and then Vance Powell [Tape Op #82] mixed it?

Yeah, Vance mixed it. I think they might have overdubbed some of Melissa’s vocals. John Mayer’s playing guitar on a couple of tracks that I didn’t record.

She’s belting out soul songs on this album.

She owns that stuff. She owns it. It alters your DNA, like records should. That’s got some feeling. She’s got a killer guitar sound. I went to private school, so I had my dose of rock growing up. I would get AC/DC and Def Leppard from my friends. Then I’d have my cousins come over on the weekend, and we’d listen to Rick James’ Street Songs. This is all the music I grew up listening to. I’ve been trying to get the guitar sounds she gets, which is almost like an Angus Young kind of thing. She came in and I was like, “Holy shit! It’s the guitar sound I’ve been trying to get for 20 years.”

What do you think it is?

Man, it’s the way she plays.

One thing about Royal is that you’ve retained a lot of the original equipment. The console and the tape deck are still here. I see there’s Pro Tools going on now.

It’s in a flight case, just to let it know that it’s not permanent. “I’ll just crate you up!”

But is there a conscious thing for you to keep a lot of this?

Yeah, it’s that, and I really like what the gear does. Music sounds better. Even when I’m recording synthesizers. On “Uptown Funk” I ran synthesizers through a 1961 Altec mic pre. It’s like somebody melted a huge stick of butter on it. All the harsh, digital bullshit – it just gets rid of it. I’m all about what I said: tipping a hat to the past, and embracing the future. I use some plug-ins, but they’re mostly emulations of the past. Like if I run out of Pultec EQs.

Everything in your racks has been emulated.

Yeah. And the upstairs studio room is being completely restored to its 1974 glory. The 8-track tape machine just had all the power supplies re-capped.

8-track 1-inch?

All tube. Yeah, man. You just run your tracks through it.

Where do you see the studio heading?

There’s a cap to the studio business, and our next logical evolution, which we’ve started, is to have a label. Otherwise we’re just working for hire for everybody else. All the great studios back in the day were just merely arms of a record company. They were there to facilitate the need of the label. Hi Records needed somewhere to record.

Sun Studios wasn’t called Sun. It was called Memphis Recording Services.

Yeah. Stax’s first record was recorded here. They weren’t trying to get into the studio business. John Fry [Ardent Studios, Tape Op #58] probably was the only dude [in Memphis] who was like, “Okay, I’m going to open a commercial recording studio.” These places were to facilitate the need of a record company.

That’s what we see David Porter [Tape Op #118] doing right now.

And that’s what I’m doing. My sister, Oona Mitchell, and I just started Royal Records. You probably saw the logo in the hallway. We need to be owning some intellectual property. If I book this place every day at X amount a day, there’s still a cap. There’re only 365 days in a year, and you’re locked in.

And it doesn’t pay the bills when it’s empty.

Yeah. There’s really no room for growth. People will always come to this place for one reason or another. It would be nice for a week, or five days out of each month, to just concentrate on what I want to do. But we’re really blessed. I’m getting a lot more calls to produce records. I like to engineer big projects, like Mark Ronson’s or something like that, but I really like to produce. I’m always giving it away for free, anyway. When someone comes in, it’s just like, “Okay, the problem is the bass player. You need to alter your bass line to match what the drummer’s playing.”

I’ve been there.

Then people always want to know, “What do you think about it?” It’s like, “Dude, you’re not paying me for what I think about it.” Engineering and producing, the lines always get blurred. Sometimes when guys are really asserting that they’re the producer, it pisses me off a little bit. It’s like, “Dude, you’re asking me what I think every five minutes. You ain’t producing shit.” And then they’re going, “Oh, we’re going to make sure that you get credit for engineering on it.” I’m like, “This is what you’re supposed to do anyway.”

Oh, yeah. It’s interesting.

I’m really blessed to have a lot of people who want me to produce their records, so I’m getting to do what I want to do. I carefully pick and choose. I like all kinds of music. I even do some bluegrass.

Deering & Down might be something people wouldn’t expect you to work on stylistically, but they’ve got songs and a great singer.

Exactly. I’ve always got one foot in the rap world, too. My son is an artist, and I help him. He makes tracks like he was born to do that. I’ve been playing keys a lot more lately. I started out in that – when I was 17 I played keys on one of Al Green’s gospel records. But only because he was going to use the bathroom – Pop had bought me and my brother a synthesizer and drums, and we were jamming out. Al says, “Willie, let the boys play on this next one.” We’re like, “Shit!”

That’s hilarious.

I’ve been playing a lot of keyboards, piano, and Wurlitzer on records. I really like doing horn arranging, and strings too. I feel like my dad and Uncle James are just whispering in my ear. All of this is becoming second nature to me. Even on Melissa’s record. It’s like, “Let’s do this. Is that cool, John [Burk, co-producer]?” John’s like, “Hell, yeah!” As Pop used to say to me back in the day, “You’ve got to hear that.” I’m like, “What do you mean, Pop?”

To hear what could be added, or what could be wrong?

Yeah, or just hear what could be added or should be there. That’s the “producer.” That’s what I try for. Sometimes you don’t know exactly what it is all the time, but you know it when you hear it, and you know what it ain’t! I’ve been working on a lot of records, man. My ears and my arranging… It used to scare me. Like, “Oh, shit, we’re doing a horn session. I hope I hear something.” Now it’s like, “Bam.”

You know where they should fit, and who to call?

Yeah, that’s ninety percent of it!

What kind of artists are you looking for with Royal Records?

Nothing genre-specific. I want unique artists. Like if I’m going to have a country artist, I want them to be something a little bit different.

Have you found some artists lately you’re excited about working with?

I’m working with a young vocalist who’s a Stax graduate, who went to Berklee. I’m doing the development. Sometimes things need tweaking.

Yeah.

Even when Pop found Al Green, it took a couple of years of developing. A lot of time the artists don’t know who they are. You have to help them.

Find their strengths.

Help them find themselves, really.

Lawrence 'Boo" Mitchell Playlist on Spotify