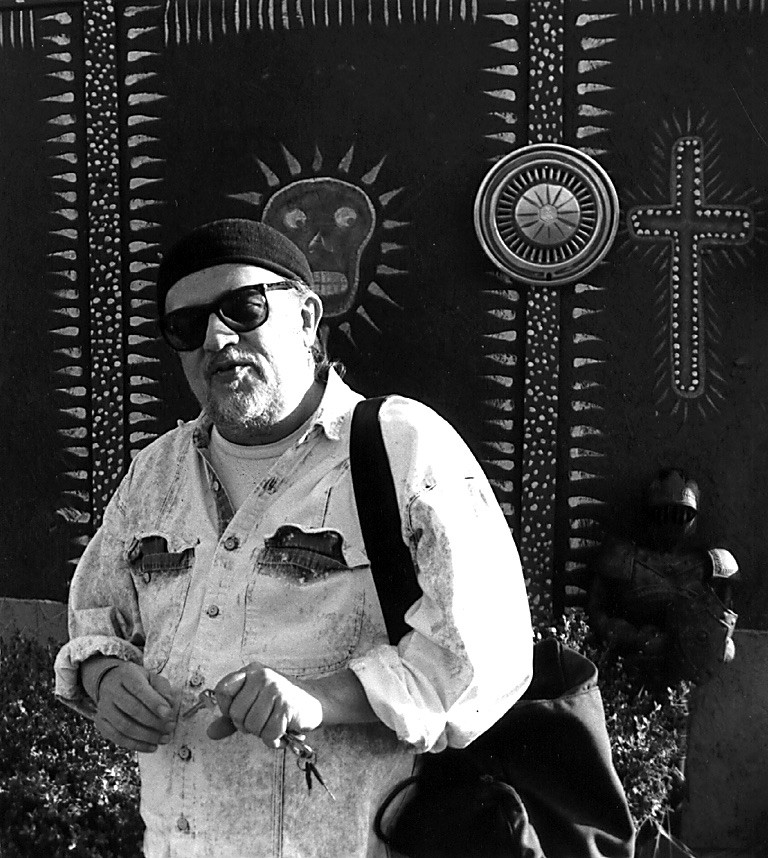

Somewhere on the thorny road to legend, hotel recording genius (and Eric Clapton victim) Robert Johnson wrote, "This stuff I got'll bust your brains out." While he may have been referring to the poison that took his life, he may as well have been describing the aftermath of a conversation with Jim Dickinson. An instant Memphis luminary, Jim has played with artists such as Sam and Dave, James Carr, The Rolling Stones, The Flamin' Groovies, Sleepy John Estes, Bob Dylan and countless others while simultaneously producing records for The Replacements, Screamin' Jay Hawkins, Green on Red, Calvin Russell, Toots and the Maytals, Ry Cooder and Big Star (to name a few). Some sane men go crazy after long stretches in the hit factory, becoming so firmly entrenched in the hyperbole and dissolute entanglements of the business that they can no longer hear music. Luckily, Jim is fine. One afternoon, we talked about his attempts to control nature, mendacity and Paul Westerberg in a lifelong quest for the "fuzzy little sound" that first inspired him.

Tell us something of the past. Did you always know you wanted to record music?

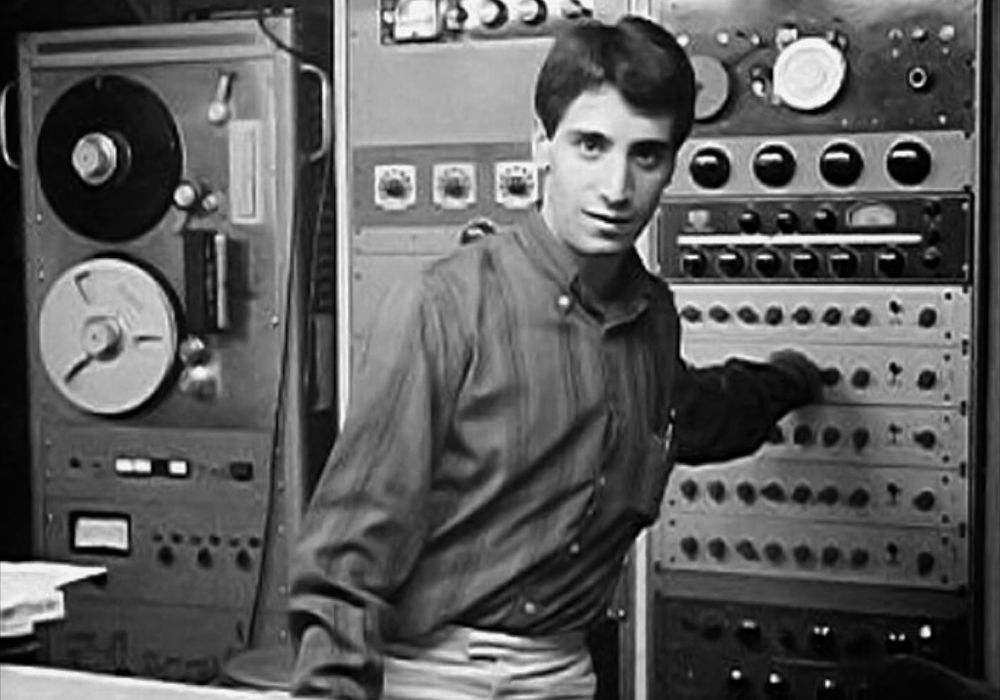

When I was a little kid my parents took me to Thomas Edison's museum. I didn't understand what part of it fascinated me — I thought I wanted to be an inventor maybe, but then I realized it was the recording equipment I was interested in.

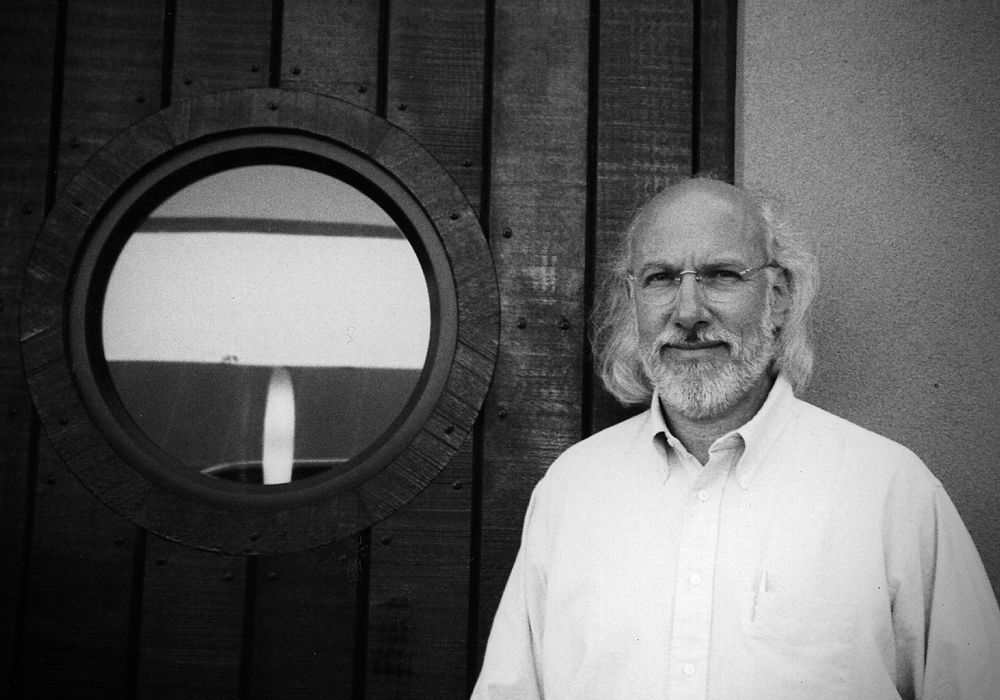

There's a duality involved in making records. How did you decide to be a producer as opposed to an engineer?

I didn't separate the ideas of production and engineering at first, and it is two very different things. A lot of producers were running their own equipment, so I thought I wanted to be an engineer. John Fry told me, "Jim, I don't think you're emotionally suited to be an engineer." And he was entirely right. Engineering was a nightmare to me. It gave me nightmares — the worst dreams of my life. I was actually going to a Freudian analyst at one point because of engineering. As soon as I quit the guy declared me cured. I was going to school at Memphis State. My wife and I were living on campus, in Veterans housing. John Fry had a family home which was just a block and a half away and he had a recording studio behind it where he had made records as a teenager. The original Ardent records — four or five singles that came out when John was a teenager, with Fred Smith as a partner — the guy that is Fed Ex now. John considered himself retired at this time, which was 1965! That recording equipment was just too close — I couldn't resist it. So we did some sessions together, and I brought some people in. Again, I didn't know what production was. Fry had a partner in the radio programming business at the time named John King. King told me about Phil Spector and Motown — identified things, like the music that comes from New Orleans. I knew about the music, but I didn't know it specifically came from New Orleans. Johnny Vincent, Cosmio Matesi. King turned me on to all that.

What was your first job in the business?

My first "job" in the business was working for Chips Moman at the American studio. He had the first pop hit out of Memphis at the beginning of what they call the "Golden Era". "Keep on Dancing" by the Gentrys — a teen-age band from Memphis. Larry Raspberry and Jimmy Hart (now "The Mouth of the South", WWF manager) were in the original band. The kids that played on the record cut this very simple cover of an old R & B tune called "Keep on Dancing" at American Studios, put it out locally, then sold it to MGM and the thing was a hit. These kids were in high school, so half the band had quit with the record number 15 on the charts, and no album in the can, because they wouldn't go on the road. Well, I never have enjoyed playing live — I don't connect to the audience. In the studio I'm utterly aware of the audience, although we're separated by time and space, you know? I feel my audience in the studio — I never have on stage. So, it was known in the Memphis music community that I wouldn't go on the road. I turned down an opportunity to go on the road with the Marquees and a couple of other things. So Raspberry, the leader of the Gentrys, calls me up one night in my little cabin at about ten o'clock at night, my wife and I are sitting there, and he says, "You know, this is my situation: I'm number 15 with a bullet and my band has quit. I need to have a band and I need to have an album. Chips Moman, the producer, won't start to record until I've got a whole band. Will you go on the road with the Gentrys?" I said, "Hell no, Larry." He said, "Well, will you come...