Brent Averill Enterprises, simply known as BAE these days, is perhaps the best-known builder of Neve-style preamps, and for good reason as their designs indeed capture the behavior, tone, and appearance of Neve preamps beautifully. For years I have used a pair of their 1073s, and they have performed flawlessly, providing that fat and warm, yet open and dynamic sound that has defined the vibe of countless records we hear every day. For those who aren't familiar, a Neve 1073 module has a mic preamp, a line-amp (with its own dedicated transformer), and a 3-band EQ with an additional HPF. The high shelf is fixed at 12 kHz while the low-shelf and mid bands as well as the HPF have rotary switches to select frequency. The 1073 is a classic modular preamp, first released in 1970 as part of the A88 mixing console, and the original has gone on to become legendary, collectible, and very expensive. To take on the task of recreating the sound of Neve's classic 1073 preamp is always a bit of a tight-rope walk, but to try to expand on the design while maintaining the original vibe and sound is to walk without a net. That's what BAE has done with their new 1023.

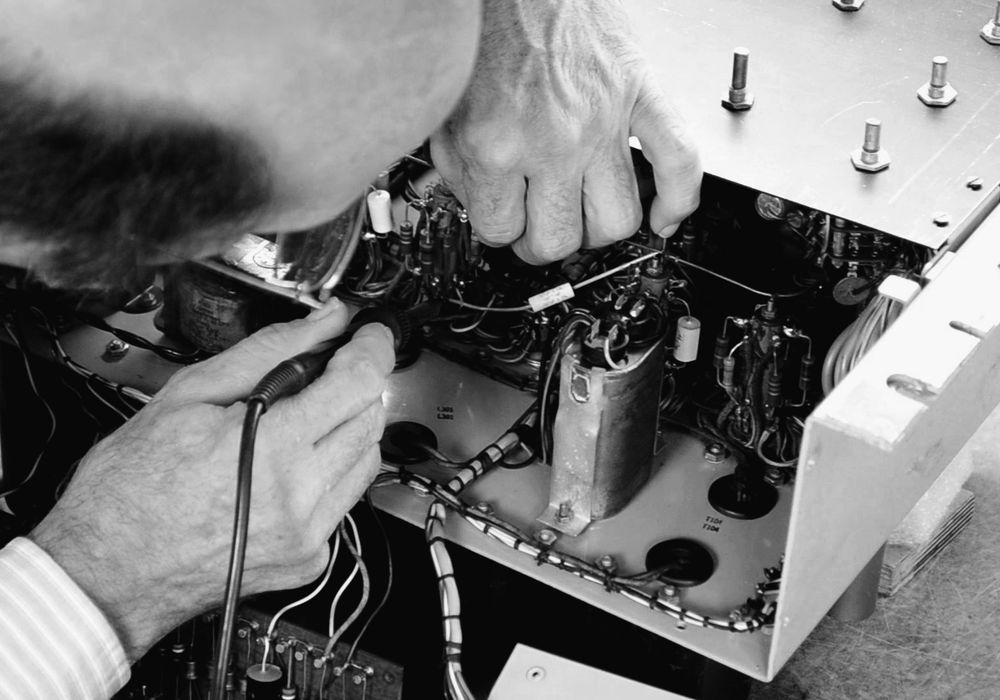

Like the original 1073, the 1023 is completely hand-wired using Carnhill (St. Ives) transformers. It has the exact same mic/line preamp as the 1073, but with significantly more frequencies in the mid and high sections. Aside from simply offering more frequency settings to play with, these expanded EQ sections also allow you to play the mid-band bell curve directly against the high and low shelves where they overlap. This capability opens the tone-shaping possibilities in very interesting and musical ways.

On the mid band of the 1023, you'll find two additional lower-frequency settings and three higher ones, which gives the 1023 the following mid EQ points: 160, 270, 360, 510, 700 Hz, 1.6, 3.2, 4.8, 7.2, 8.2, 10 kHz. The overlap with the low shelf, for example, allows you to boost 160 Hz with the mid and cut 220 Hz with the low to achieve a very tight rise in the lows that doesn't overpower in the deeper frequencies or get too muddy up around 300 Hz. The sound is quite different than simply boosting 160 Hz. This particular EQ setting is really fun for fattening up distorted electric guitars, warming up female vocals, or getting a floor tom to growl in a new way. The low end is always tight, punchy and satisfying.

On the high shelf, rather than the fixed 12 kHz shelf of the 1073, you'll find settings at 10, 12, 16, 20, and 24 kHz. The expanded high frequencies in the mid section start to make sense when you realize that you can really play the mid band against the high shelf, just as you can with the low. With drum overheads, for example, try boosting 10 kHz on the mid while cutting 20 kHz on the high, and you'll get an increased sizzle with a de-emphasis in the air region that is reminiscent of some vintage recordings. Or, do the opposite to control brash cymbals while adding some excitement in the air region. The possibilities are pretty limitless, and experimentation is fun and rewarding. As to be expected, the highs are smooth and musical, just as a Neve should be, but the added frequencies on the high shelf make the 1023 more versatile and fun to use.

The 24 kHz setting is my favorite feature on the 1023. I want to deviate for a moment and discuss what it means to be working with a frequency that is, presumably, outside the audible range. First, the curve of a 24 kHz shelf is going to reach down into the audible range, especially on a wide-Q equalizer like a Neve. As you turn it up or down, it will drag lower frequencies along with it. Second, inaudible frequencies will impact the character of audible ones by way of the harmonic relationship. What this means is that, while you might not hear what's happening at 24 kHz in and of itself, you will easily hear the impact of 24kHz on the sound of

your recordings. (To further deviate, it is interesting to consider that Sear Sound in NYC has a custom console with 30 kHz shelves on every channel. Interestingly, Walter Sear (Tape Op #41) stresses that the digital formats render frequencies in that region as noise, thus negatively altering the harmonic relationships. Analog tape, he argues, preserves those relationships accurately and therefore sounds better.) The practical reason Walter Sear or BAE would put such high bands on their EQs is that the impact on the recorded music is so satisfying to the human ear. A tiny boost of 24 kHz on a female vocal brings out an ethereal quality; on acoustic guitar, it helps rhythm parts occupy the realm of ride cymbals with less competition; on overheads, it seems to lift a veil you may not have known was there; and on the whole mix, 24 kHz can bring a lot of energy and openness without harshness. Because the circuitry is characteristically smooth in handling high-frequency boosts, playing with the 24 kHz shelf on the 1023 is always satisfying, even when boosting at extreme levels.

With the EQ disengaged, the 1023 is indistinguishable from the BAE 1073 I'm so used to. If you know what the 1073 sounds like, then you'll know what the 1023 mic preamp and line amp sound like. (If you aren't familiar with the Neve sound, expect to fall in love with the warm yet open and detailed sound.) These are first-rate preamps; they sound amazing and handled everything I ran through them beautifully.

One of my favorite applications of the 1023 -and why I see an investment of this magnitude to be well worth it -is on an analog 2-bus chain while mixing in the box. Running mixes through the 1023 at unity gain without EQ can add depth, punch, and width to a mix that can give you a great deal of the sonic characteristic of mixing through an analog console. Switch in the EQs and open the top with a slight 24 kHz boost, and things get really nice really quickly. Again, when you consider this application, it's easy to understand how the pair of 1023s I've had on hand have been in constant use since I got them, whether I'm tracking or mixing.

Even though the 1023 is neither phase-linear nor surgically exact, I'd highly recommend that mastering engineers who are looking for a "color box" check out a pair, as I loved their impact on full mixes with and without the EQ engaged. Mastering engineers will appreciate the added frequency settings in the mid and high EQ sections, and that 24 kHz setting might just be the fairy dust you're looking for in many cases. Combine that with the analog body and punch you get from the line-amp transformers, and it's clear that the 1023 can bring a lot to a mastering situation where the client is looking to you to warm up and enliven mixes with an iconic analog flavor.

There are two versions of the 1023 available. The newly-announced 19" 1RU-height rackmount version operates standalone, and it includes phantom power, a DI input, polarity reverse, EQ defeat, and a 300/1200 Ohm input-impedance selector. An external power supply from BAE can power two of the rackmount units. The 1023 module version is a drop-in replacement for Neve modules, and it requires a 10-series console frame or powered rack to house it and to add phantom power and DI functionality. (Check out the 2 and 8-channel racks from BAE, for example.) If I owned a 10-series console, I'd be looking to get at least two channels of the 1023 in there, as I know I'd reach for them all the time during tracking and mixing. If you can make the financial leap to get a pair in either format, I know you'll find yourself using them constantly. I happily welcome the 1023 to the 10-series family. ($2975 per module, $3200 for rackmount version with power supply; www.brentaverill.com)

Tape Op is a bi-monthly magazine devoted to the art of record making.

_disp_horizontal_bw.jpg)