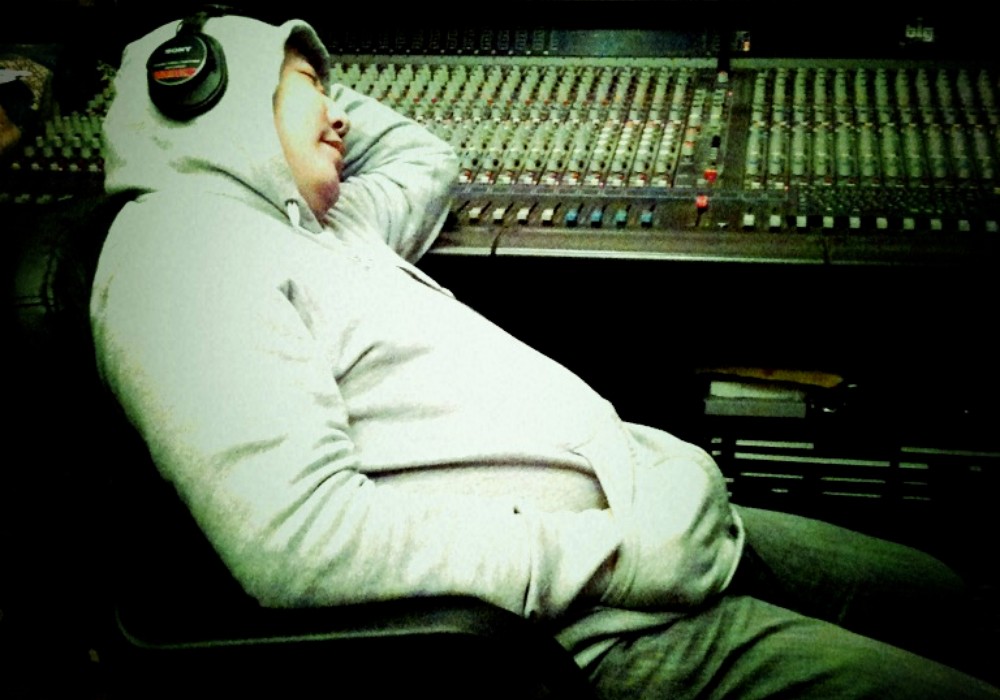

Stuart Sullivan has worked with a diverse list of artists. Sublime, James McMurtry, Tejano greats Little Joe y La Familia, The Meat Puppets, The Dead Milkmen, James Cotton, and Willie Nelson have all tracked with Stuart at the faders. He often teams with producer Paul Leary of the Butthole Surfers (in issue #94 as well) and in 2001 he opened his own studio, Wire Recording, in Austin, Texas. I visited him at Wire to discuss his techniques, experience, and the changing landscape of the recording industry.

Let's talk about the CCA LA-1D limiter that you have.

From what I understand, they were made by a group of RCA engineers that worked in the broadcasting wing. They started their own company called CCA. If you look at a schematic of it and you look at the schematic of a Gates Sta-Level it's stunningly similar. Nonetheless, they made a few changes: the input transformer was the transformer from the original LA-2A.

How does it color your tone?

They're limiters, so you have a situation where you can set your output to a certain level and then with the input you can keep bringing it up. You can just kiss it and move it around a little, and you get limiting but it's not a whole lot of coloration. As you dig in harder and harder, two things happen. More and more color, distortion and artifacts from the compression come to the fore, but the volume doesn't change. There are a lot of ways you can play with it and the tone changes depending on how you play with it. I find myself using it a lot on vocals, bass guitar, some on really crunchy guitar; I've used it on piano a number of times. Some of things I've been surprised I didn't like it as much on are drums and percussion. I think the attack thing is off, but a lot of the melodic instruments it seems to track really nicely.

What do you use on drums?

The Neve. I fell in love with some Neve 2264 compressors. You're probably aware of the Neve 2254s, the big square ones. They are a little bit slow for me. I was working at a place that had some 2264s and absolutely fell in love with the sound, the speed and the quickness of them, and just the tonality of them. A number of years ago, I was out searching for a pair and a friend had what looked to me to be a 33609, a stereo Neve compressor. Instead, it was a pair of 2264s laid sideways. Fred Hill in Nashville added some attack switches to it because the natural attack is very quick on these units. Having the attack switch, at least the first three and four clicks of it, I found to make them wildly more useful. It's hard to argue with the sound of an [Universal Audio] 1176 crunching on a set of drums, and in that same quadrant the [Empirical Labs] Distressor has the things it does. The one thing about the Distressor is that it's an analog modeler. It emulates, and very well, a variety of things. It's got three or four different compression styles depending on where you have the attack, release and ratio sets. The one thing that's distinguished it is that it's been a very colorful compressor, it's not always the cleanest compressor, but it has a lot of controllable color. It's about the only meter in the business that doesn't seem to lie. My whole life, I don't think I've seen a machine that metered more accurately than that one in terms of compression level. It may be meter ballistics, but there have been a lot of LA-3 units that respond quite slowly.

What do you do for drum mic'ing?

When I'm recording drums I often times do a variety of things. Besides the basic mic'ing of the drums, I'll have a stereo room mic, like the [Neumann] SM 2. I have a bathroom, and I'll have a bathroom mic. I vary between the [Neumann] U 67 and a [Neumann] TLM 170. Both of them have good top end and I can put them in omni or figure 8. Those go in the bathroom and those get crushed. If you really want to commit yourself for life, give it a little preamp distortion; just give it a little grit for that total, bug-eyed experience. Oftentimes I'll have a Coles mic somewhere around the drum kit. Whether it's four or five feet away or whether it's right up on the drum kit, I can't tell you. My assistant knows that's the floater mic. He'll put it up and if I don't like it, he'll move it.

How many close mics are you using on a drum set?

I love to do just a pair of overheads. Sometimes I do them in an X/Y form, a lot of times I do them spaced for the cymbals, but a lot of times I'll also have to put up a third mic for the ride. I have a Shure SM57 that I like for the snare top, that we took the transformer out of — that's a Tape Op trick! I tend to mic the bottom with a Schoeps 221. Other times with the snare drum, I might do a 64 and I have a [Sony] C37A I like on the snare sometimes. A lot of the jazz stuff I do I'll do an X/Y overhead, and just work until everything's there, and I won't have a snare. I'll just have a kick and overheads. You've got three mics and you're off. With a kick drum, you kind of move around and hear where there's a really tight wave set up, then you put it there and tilt it just a little bit. If you don't tilt it, you'll blow you off your bum. Just off to the side. Basically what I want to do is get it where the low end wave is set up really nicely and capture that with a little tilt where you have some control. If you move out you'll hear different spots of the kick drum open up and the farther you get it will become God-like. I've only got a limited amount of control, but I want to get more sub than I'm getting from a mic that's either in or just in the hole. So I use the ambient mic, and again, those ribbon mics in general, like a [RCA] 44, are awesome. For the jazz thing, it's a three mic set up, for a rock band, it's 15 with kick, kick, snare, snare, hi-hat, tom, tom, overhead, overhead, ride, stereo room counts as two, floating room, mono room and three talk back mics. Those talk back mics, slammed down through an API compressor — if they don't talk, those can be awesome. Once in a while that's just the coolest thing in the world.

Depending on the music, it could be a minimalistic or wider approach.

A lot of times with Groupo Fantasma, if we want to get into it, I'll do five. One or two overheads, kick, snare, hi-hat.

With Groupo Fantasma, do you record them live?

As much as possible, minus the horns. What we'll do is have the drummer in the booth, Sweet Lou the conga player will be in the piano room, and then I'll have Beto, Greg and Adrian. Often times I have a horn in the control room. Sometimes they'll have drums and two percussionists. You kind of get stretched out a little bit. There are times with Grupo Fantasma, I would take the two tom mics, run them through the Altec and just crank the input and get a lot of preamp distortion, I don't mean a little. You pull a little top and off and tuck that in there, and that's the sound you've heard. It's exciting and cool. That's the thing about drums in general. You've got the drums and the player. That's the biggest variance. Weak drummers, I'm sorry there's just not that much you can do. You can sample and trigger and stuff, but if you get a great drummer, everything's different. If you can keep the real tracks, it's a dream, there's no loss of grace or dynamics or subtlety. The room mics all sound completely natural and things line up and are clear and defined instead of having the midrange scooped out so the midrange of the sample can come in.

You had a lot of success with the Dead Milkmen as well. What were they like?

I did a couple records with them [with Brian Beattie producing, Tape Op #53]. That was late '80s, I think. There were such unbelievably low key, normal guys. Rodney Anonymous was as he appeared — a whirlwind of activity and a lovely guy. He was funny. It was friendly, goofball-ish, hilarious stuff. It was wonderful in that sense. All four of them were really pretty nice. Nobody was acting out, going crazy, or getting drunk — there was none of that. It was fun, a few hi-jinx and kind of hanging out. A lot of bands you see on stage and when you see them in real life, they're not the characters you see on stage.

Do you remember tracking "Punk Rock Girl?"

I don't remember the actual moment of it. A lot of times you're tracking the song and it's the first time you've heard it. It's only later that you lock into it. I don't remember the first time I heard a lot of songs I've done because I didn't know the song. It may take me three or four times because you hear ten songs, you're loading them in as fast as you can. It takes you a few days to get familiar with all of them.

Did they spend a lot of time in the studio?

It would be two to three weeks from start to finish. Because they were fairly sane guys, things worked efficiently. There wasn't a lot of problems, it was one of those things where you were just working. Sometimes it's horsing around, chaos or wasting time. Other times, it's just slow, steady work. That's a good way to get stuff done.

How do you deal with running a business when you're actually in session?

You have to compartmentalize your head. When you're working on music, unless I'm really not into the music, I'm generally taken by it. So, I'm not going to let that overwhelm me because I've got something more important to deal with. My worries about money shouldn't interfere with my work because if they do I'll have less work and more money woes. When I'm working I'm good about paying attention. Actually, I have a bit of a problem because I often times don't return enough phone calls and I take short breaks. If I take a five or ten minute break I'd rather chill than spend that entire time on the phone.

James Cotton and Pinetop Perkins did Joined at the Hip with you. Did they talk about the days of playing with Muddy?

Cotton talked some about Chess Records. Most of those talks were from the perspective of try to play well and not get in trouble. He never said not get in trouble, but I got the impression between Leonard Chess and Muddy, those guys weren't expected to be characters. They were expected to be characters on cue. When they were in the studio they were expected to nail it. They also did take after take after take, they would a million takes and that would drive everyone crazy because it's so hard to keep doing it. He's talked about how Muddy would demand money from Chess and Leonard would try to shake him off the track and say, "I'll buy you a Cadillac." Muddy would say, "I don't want no damned Cadillac, give me cash so I can buy my own damned Cadillac!" James also talked about the old South, which was kind of creepy. You realize this is a guy who not only lived through that period of music, but also lived through that period of oppression and still has a great attitude. I'm always amazed and impressed by that, too. Certainly he has a right to harbor bitterness or anger. If he does, he doesn't show it.

What keeps you going?

For me it really is about great creation and great music. There's an art side to it because that's what we're trying to do and commerce is crucial. People have to make a living to be able to keep doing this to a large degree. We're in a recession and we're in a situation where it's hard to make a living at the best of situations. Any time there are problems like this, there are opportunities lurking beneath the surface. Being able to lock into those opportunities is what's going to make the difference in the future. I'm hoping and believing that it's not just a niche anymore, which is what I've kind of maintained, but these expansive styles of music are going to help me open that door. I've done Texas Tornadoes, Freddy Fender, Sublime, Butthole Surfers, Willie Nelson, Poi Dog Pondering, bluegrass bands, big band jazz stuff and operas. I've been watching more and more people over the last 10 to 15 years appreciate broader styles of music. It used to be that identities were built around a singular association of music. That's been breaking down to the opposite extreme. I think that's something I've always felt a strong pull towards and always been a fundamental part of my career. I don't know where we're going but I'm ready for it.

Tell me about this API console.

I got it from a guy in Chicago who had it for a few years. He got it from a broker in L.A. who had bought it out of storage where it'd been for 17 years, from the time it was made. This gentleman bought it and had it for five to seven years, then it went to the Chicago guy for a couple of years. Eventually his wife got mad and wanted it out of her basement and I was able to pick it up. It had never been in a commercial studio. Because I had a smaller API temporarily, I was able to take the complement of EQs that I wanted. So I chose almost all 550-As, but I wanted a few of everything. I really like the 560s, so I've got five 560s, then I've got two 550s, which are the predecessor to the 550-A, but a little bit cleaner in my opinion. Then I got a pair of 554s, which have chips in them but they have sweepable frequencies. I adore the 553s, which are Pultec-type inductor EQs. You crank that type end a little bit and it just sings, it's not harsh. So I picked up four of those, then picked up four more, and then picked my favorite four. That's the complement of 36 EQs. I really kind of loaded it with exactly what I wanted for EQs. I had a pair of old 525 compressors. Love those. I put an Uptown moving fader system on it. The monitor section already had the pan pots. Most API monitor sections are some form of the juke box, which is just a push button — left, center or right. This came with what's called the 812 P module and so you have left to right pan pots on every channel. Since this is a unique API and was made to be a quad board, it also has front back panners. The front back panners on the input consoles have been disconnected so you don't have any problems. On the monitor side, they still actually work. Then the next step was to upgrade it to modern times. A friend of mine, a great tech named Greg Klinginsmith, went through great trouble with me. These consoles, almost all of these, it's a 32 input console, it holds 32 preamps, 36 EQs, a monitor full of chips — but it's got one pair of 3.5 amp power supplies for the whole thing. Having used APIs in the past, I can tell you that's a problem. There's one I used for years and years that still has it that way and you hear it give up when you drive it hard, especially on the low end. So the first thing we did was redo the power supplies and now I have three 5 amp supplies on there. I have one for the EQs, one for the master section and one for the monitor section. We recapped everything — not just the channels but all the sub groups and all the summing amps. I used Panasonic FCs throughout all the re-capping. Greg went through on each individual module and changed out some screws with nylon screws and washers, and put a much larger, braided ground on it to keep the ground more singular and solid. He also put down a couple of bleeder caps because radio frequencies weren't the problem back then that they are now. I think there have been a couple of functional mods on the console itself, they have four echo sends with one knob. I put a concentric knob in there so you've got one knob that goes to 1 and 2, one knob that goes to 3 and 4. They've got two cue sends and you have to push the button to activate each cue send, I just made it so you push cue 1 to activate the cue sends, push 2 to make it pre. So they can be pre/post. We replaced some resistors with a higher quality resistor with lower noise. The preamp is a pristine 312. In the listening monitor section we put Jensen transformers and John Hardy 990 op amps in. The idea is that anything we listen through, we want it to be as clean as possible. So rather than have the old API transformers or the API 525s, which are beautiful and colorful, but if we're monitoring I want my screen to be clear. Because it was cheap when I found it, I ended up buying a whole other Uptown Automation System. Uptown's been out of business for 15 years and they used 486 computers. So if you want a board or a piece or a part if you can find it, you're hung out to dry. So for $1,800 I bought a whole new system and have a back up system, but this one works great. I love it. So now it is a vintage console with lots of new components. This is not a remake, it's literally what they were after in the first place. If you want to hear the legend, this is it, an original API in great shape.