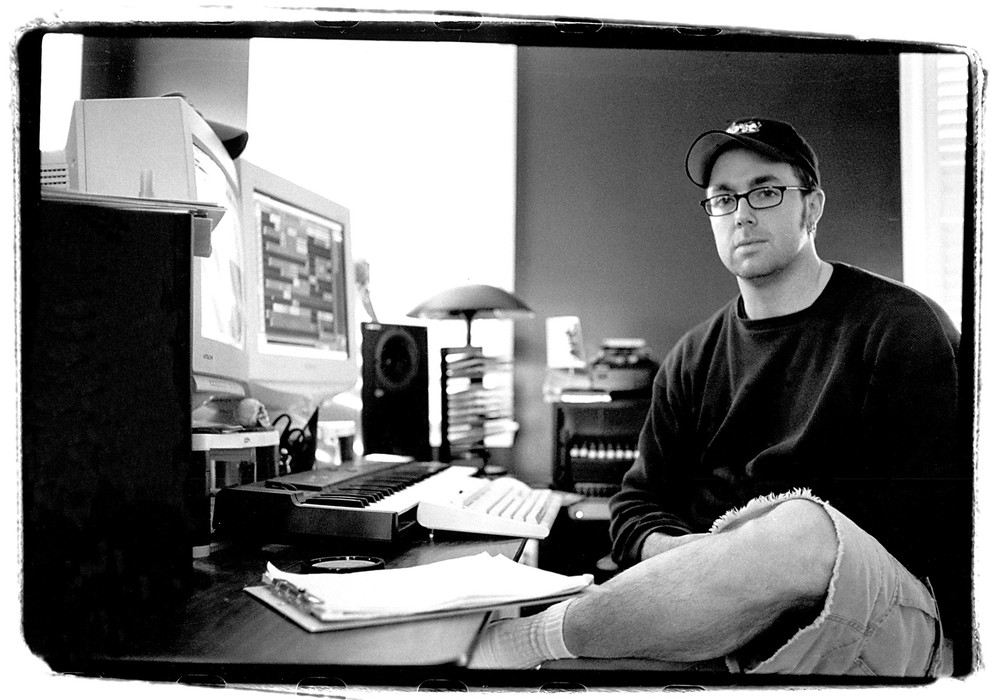

Steve and I interviewed Mike McCarthy in 2009. Somehow four years went by before our Austin issue came together. So here's our chat from 2009, and realize that Mike has gone on to do even more records. -LC

Mike McCarthy first came to my attention when he started working with the band Spoon [Tape Op #27], for whom he has produced four albums. Mike's produced five albums with ...And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead, plus albums with artists such as Patty Griffin, Heartless Bastards, Dead Confederate, Wild Sweet Orange, Alberta Cross, The Sun, White Rabbits, Crooked Bangs, Girl in a Coma, and AM Taxi. His career began many years ago, as we shall see below, and it might not be a very typical path that led him to Austin, Texas...

Mike, where in the hell did you come from?

I grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio. I always wanted to be involved in the making of rock records. I was a huge Beatles fan — a fan of rock records in general. I had some friends that were moving to Nashville. I didn't really think about it being the country music capitol at all. I was ignorant. I was like, "I can go to school, try to get some kind of normal degree and be in music." But I really had no intention of going to school, ultimately. That would have been my parent's wish. They were not necessarily thrilled with the idea of a career in music for me. I went to Belmont [University, in Nashville] for one year. A lot of the people that are executives at Nashville record labels and publishing companies went there. Famous country singers went there. All of these born again Christians that were in the dorm where I stayed were convinced I was the devil and that I had a poltergeist in my room. I was in a metal phase at the time. Iron Maiden was my favorite band.

Nashville is its own world.

It was so weird for me. The South was major culture shock to begin with, along with the Belmont weirdoes. I got lucky and was hired by an upstart [publishing] company as an in-house engineer and tape copy person. They also decided that they were going to have a record label. They had a simple 8-track studio with a Soundcraft board and a Tascam tape machine. They had a couple of groups they had signed to the label as "college rock bands," and Vanderbilt had a killer radio station there, so I started to learn about R.E.M., The Replacements, Jesus and Mary Chain, Kate Bush, Sonic Youth, Jesus Lizard and all the 4AD groups, etc. This situation was attributable to my long-term connection to what many now call indie rock. I had bands come in and do country demos during the day, and at night I would record friends of mine. I got hired there when I was 19, and it was over when I was 23. They then sold the company to BMG and let everyone go. I think I pretty much stayed there from 9 a.m. to 1 a.m. every day. This was 25 years ago.

You learned a lot though, right?

Yeah. I thought, "This chance is never going to happen again. I have to take full advantage of it." They wanted me to make demos. I was being paid a salary to learn all this. I'd be hiring who I thought were the cool players, who are now the top session guys in Nashville. I had an 8-track and had to get it all submixed on the fly — you'd have to record five songs in three hours. I didn't know how to record drums or anything. I just learned all this stuff on the job. That's when I first got into compressing the overheads on drums and really compressing vocals. These were things that I came upon by experimenting and liking the result. I had to have the drum mix set on the fly. So if you wanted reverb or gates — and that shit was big in the '80s — you had to do it while the performance went down — no going back and adding it. I learned how to program drums (on the LinnDrum) and record live bands. We eventually got a 16-track, and were allowed to hire Fairlight operators for sequencing. After that gig was over, I became independent and worked on any session I could do there.

Some people might not know that session lengths are dictated by the unions in Nashville.

I had to deal with union cards, which you don't have to deal with too much now. I had probably two union sessions last year. Big string sessions in Nashville were weird too. They're always taking breaks. So much setup and so much tear down — so expensive, and they're there for very short periods. I got to see all this stuff that was pretty beneficial for me. I think a lot of the studio owners that I met were into helping me out with my producing projects. Ultimately I left Nashville because I wasn't making music (for the most part) that I wanted to work on. Adding to that, if there was a cool band that I produced, they would get a major record deal and then I'd be out of the picture. "Mike who? No, how about so and so..." I did engineer a few big-selling, Grammy-winning records, but that meant nothing to me because it wasn't rock music. I was very frustrated. Eventually some friends mentioned that Austin had many great local rock bands, but that there weren't any real producers recording them. This was 1994 — I had a family at that point — two daughters and a wife — so New York and L.A. were definitely out — too expensive, and I had no good producing credentials. So we moved to Austin, and I basically started over and got into a situation with another company that was like my first gig, with a salary. They said, "The reason you're here is to develop a new catalog for publishing," though the company never did any deals with the bands I was bringing in. This made me realize I would have to make my producing career happen on my own entirely. So I produced several Austin bands, one of them being ...And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead.

You recorded them independently?

I was just bringing them into the studio on off time. We recorded the album Madonna that Merge [Records] put out.

How had you met those guys?

I always asked every local band I was recording what other bands they were friends with or who they thought was cool. Then I would find out when a show was and go hear them. I would hit the street every night for the first six months we lived here and look for bands. It was a brutal schedule, but necessary. I would be in the studio all day (9 a.m. to 7 p.m.), see my kids and wife at dinner time and then spend nights and weekends seeing bands. I couldn't do it now. At least not the 9 a.m. shit.

It seems like a unique situation to me — to have a space to work out of where you're being paid by them to work there, but you're doing other jobs on the side.

They had a huge Nashville songwriting catalog that brought in millions. They didn't give a shit about what I was doing. Many bands I wanted to work with would not [do it], because of the fear of the company wanting to sign them to an agreement. This eventually proved to be a moot issue because they didn't really want to sign any of the bands I brought in anyway. They were paying me, though. Nice people. It was a nice idea that just didn't work. It made an autonomous recording situation for me though.

The publishing part?

Yeah. It was tough to deal with, understandably. Right after I finished the ...Trail of Dead album, I was hired to produce a band that had been signed to Elektra called Goudie, so I left the company. Then I began to record artists in New York and Nashville again. ...Trail of Dead signed to Interscope, and Spoon and I began working together. I made more albums with ...Trail of Dead [Source Tags & Codes] and with Spoon [Girls Can Tell and Kill the Moonlight] — recording/ mixing/producing. The thing about being in Nashville again as well was that a lot of the people that I had met in my first tenure there had become label execs and A&R. They were like, "Hey Mike, we need you to come and make this country artist sound more like a rock record." Half the time I'd be producing, half the time I'd be co-producing, engineering and/or mixing, so with the money made I was like, "Alright, start buying microphones — the first order in the recording chain." I put as much money into buying gear as I could so I would eventually have my own studio. I felt this was necessary to carry on with my own ideas of how I wanted to make records, and not have to pay an entire recording budget to another studio — not to mention job security.

Working in Nashville studios must have been different.

Most of the studios in the '80s didn't even have 24-track, 2-inch machines until the [Studer] 827 was issued. All the tape machines were broken everywhere and nobody would fix them. Most places had these horrible Mitsubishi open-reel [digital] tape machines — they sound worse than ADATs. I would record and be like, "God, I suck. It sounds like shit." I'd leave every day with a fucking headache. I couldn't use EQ at all. I started to do more stuff on tape again and I was like, "I do know what I'm doing." Then in the '90s people from L.A. came to Nashville and built better studios with good vintage gear. Much cooler.

You've got a history of working with groups like Spoon and ...Trail of Dead where you've done a number of records together. What do you think brings that on?

I don't know. I treat most projects like I'm a member. I don't know if anyone else would say that — maybe that's delusional — but I approach it as if it's that important to me. I get in there and really want to make sure that it's personalized, that everybody comes up with what they want. I think people appreciate that to some degree, although I can't say it will go on forever. Bands have got to know that you care.

It was quite a long path for a while.

I made the first two Spoon records with nothing. I'd bring my microphones that I had started to collect and my pair of [Yamaha] NS-10s over to Jim Eno's garage. He had an [Ampex] MM 1200 16-track, which I knew how to record on — 16-track heads at 15 ips. Jim had an additional 8 tracks of 16-bit Pro Tools as well. He had a Trident 24 [console] — I had done a lot of work in Nashville on 80 series Tridents, so I knew the monitor side (right side) was what I liked. I'd sit down with Britt [Daniel] and Jim and go over lyrics and musical parts, trade back and forth on bass, guitar and keys — "Lets try this" — Get real tight with it almost like we're in the band together. If you look at what we did on their album Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, Jim has a bigger studio with more equipment, and we mixed at Ocean Way Nashville on a big [Neve] 8078 with automation. There was an agreement to continually progress [on the] technological side and on how far we're gonna go with the production. They started from real sparse things to a bit more involved. Britt and Jim kept getting better with Pro Tools operation. That would allow me to remain in that objective position with them, where I can sit back and go, "That's great. Let's get rid of that. Let's move this." We started getting into that a lot. On the last two ...Trail of Dead albums, we would have 24-track, 2-inch tape, Pro Tools, Logic and my [Akai] MPC4000 all locked up together. Source Tags & Codes was two 24-track tape machines locked up together — no Pro Tools at all. I even had my old LinnDrum instead of the MPC.

SC: Kill the Moonlight is still my favorite Spoon album.

Britt and I were sitting in that room for hours during the daytime, hallucinating from the heat while making that one. That summer was seriously hot — 100-degree days every day. When we mic'ed anything we had to turn the air conditioning off while recording. We were buzzed and nodding on iced green tea. We were very focused though — no distractions.

Any thoughts about your future?

I want to be in a way that I can have people come in and have a place to have their first shot at making a record — the way I used to do with Spoon and ...Trail of Dead. I want to do new things. Would love to produce some veteran bands as well. I would love to travel some, work out of the country if possible. I would like to be involved in having a label possibly.

More of a career guidance kind of thing?

Yeah. I feel like the thing that's with any of these groups, and the reason that they come back to me for more than one record is I work with them in a constantly developing situation. We've always had this vision of where it's going or, "Where do we want it to go?" Those are the kind of artists that I like to work with. I am not into the, "Go make one record and then never see them again." It's not as fulfilling.