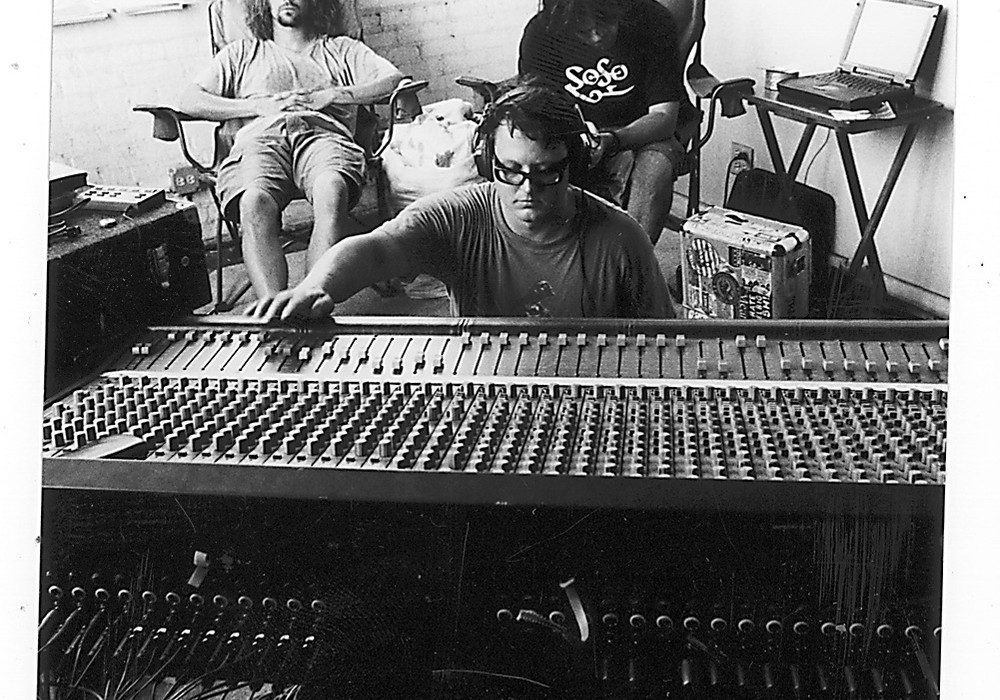

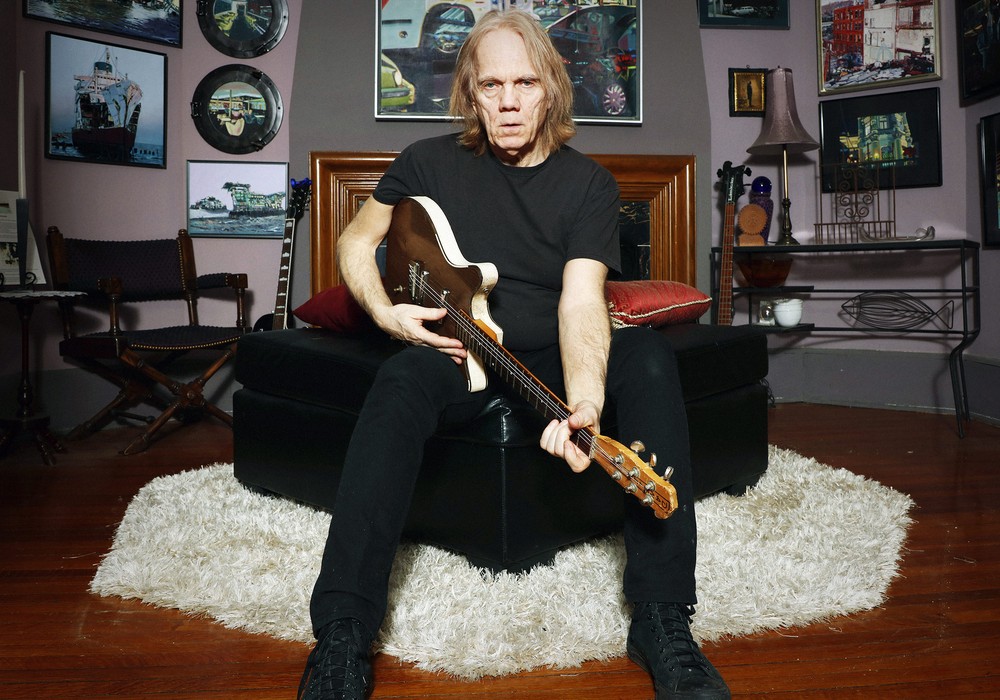

Dave Jerden has engineered, produced and mixed some of the most cutting-edge, ground breaking records in studios all around the world. Just take a listen to his engineering and mixing of Brian Eno and David Byrne's My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, Talking Heads' Remain in Light and Herbie Hancock's Future Shock. As an engineer, he has worked with some of modern music's greatest producers such as Bill Laswell, Michael Beinhorn, Brian Eno and Steve Lillywhite. Jerden is a technical master, unconstrained by conventional thinking and confident yet humble. As a producer he has helped artists like Public Image Limited, Jane's Addiction, Alice in Chains, Social Distortion and The Offspring make stunning records. Currently, he co-owns Tranzformer Studios in Burbank, California, with his long time engineer Bryan Carlstrom (Tape Op #28). The studio is managed by Annette Cisneros (who has also engineered alongside Jerden and Carlstrom for many years) with assistant engineer duties going to John Nuss. Dave Jerden and I sat in the patio lounge at Tranzformer Studios for a pleasant conversation covering a multitude of topics.

You mentioned that your dad was into music.

Yeah, my father was a bass player. When I was about 14 years old I met this kid in class who played guitar, so I borrowed a bass and there was a drummer that lived around the corner. We started a band. My dad bought me a '62 [Fender] P Bass, a P.A. system and a bass amp. I started playing with some really good people. I actually have some of these recordings of my band, Praying Mantis, from 1967.

Wow!

I was in a band called Electric Circus and the singer was Lana Hale, the daughter of "Skipper" [Alan Hale, Jr.] from Gilligan's Island. She was a great vocalist, so we got a lot of gigs. I played until I was 24 years old, and then at 25 I went to an engineering school called the University of Sound Arts. I used to go to the studio with my father and I'd focus on the engineer. I'd watch him set up mics and get levels — everybody deferred to the engineer and not the producer. It was like the engineer was the guy. That's what I wanted to be. I'd heard it was really hard to get a job when you got out of school. I got a phone call from a bandmate that I had played with named Doug Parry. Doug knew I'd finished the engineering school, so he and I partnered up. We started Smoketree [Ranch Studios] in a barn that he was rebuilding on a ranch out in Chatsworth [California, a suburb of Los Angeles]. That's where Steely Dan did one of their records. Later he owned two studios, Andora and Smoketree, and he now owns Rack Attack [Rentals]. I was with Doug for about seven months; then I went to another studio that offered me a job — Redondo Pacific. Then I ended up at Eldorado [Recording Studios] — I learned a lot. There had been engineers there, but they'd all left and I was the only guy. I was working around the clock. I'd do everything from country music to disco to rock — just continuously recording and learning. I worked with a lot of great people. I had been there for about a year when the studio manager said, "Brian Eno [Tape Op #85] wants to come in." We had put in Mix Magazine that we had this new Lexicon 224 Digital Reverb... but we didn't! I knew this guy who was an equipment broker; I called him and asked if he had one, because Brian was coming in to look at it. He said there was one going to the Village Recorders, and he'd let me borrow it. I learned how to use it that morning! Then Brian came in and he had a cassette tape. I put it through the board with the reverb, delays and other effects I had. He goes, "Wow! Do you like this stuff?" I said, "I love it!" He says, "I'm doing an album with David Byrne and I want to book time with your studio manager." That became My Life in the Bush of Ghosts.

Are you aware of this website for My Life in the Bush of Ghosts? The website has the multitracks to two songs that you can download and remix.

I gotta check that out! It was pre-MIDI when I recorded that. All the loops are real loops and they could be 16 to 20 feet long. I'd put masking tape as a guide on microphone stands and then run it through the heads. I'd have 24 tracks on the multitrack, then I'd mix that down to two tracks, make a loop out of that, put it on two tracks of a new 24-track and then we'd add from there. We'd build it up that way — all of it was experimental as we went along. Brian used to like to use what he called "found objects." It was really interesting. We'd do things like take a can (that you'd put film) in and a big glass, I'd put a mic at one end and we'd hit the reel can and the glass on...