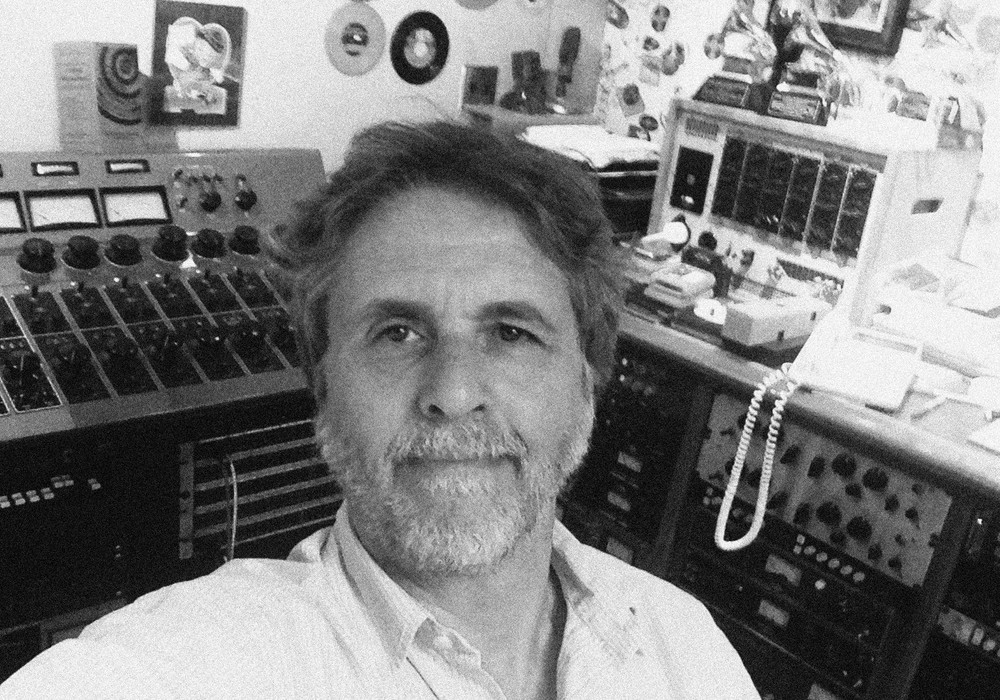

It's not an exaggeration to say that most non-Icelandic people come to know of this tiny island country through the records Valgeir Sigurðsson made with Björk, and there's no denying that these records were some of the most innovative, genre-bending works of their time. From an engineering and production perspective, Sigurðsson's work with Björk made her desire to blend pop, punk, electronica and neo-classical sounds and sensibilities into a sonic reality, and doing so required a fearless exploration of cutting-edge recording and production techniques.

While hanging out with this softly-spoken yet candid Icelander, I came to quickly realize that Björk was really only one snapshot in a long-arcing career that, in many ways, is only now starting to hit its full stride with the development of his own label and creative collective, Bedroom Community. Artists like Ben Frost, Nico Muhly, Sam Amidon and Puzzle Muteson collaborate with Sigurðsson to create albums that defy genre, and therefore easy description: Frost's music can sound like wolves mauling prey; Muhly's like the a global information network on speed; Amidon's like an Appalachian lucid-dream; and Sigurðsson's like a wistful, longing landscape. Yet, all of these albums cohere around Sigurðsson's highly articulate production style that elegantly combines acoustic recording and electronic manipulation. I met up with Sigurðsson in his Greenhouse Studio, housed in an impossibly entwined residential cul-de-sac about 10 minutes from downtown Reykjavik. His studio is uniquely modern and airy, designed to let the rain be heard and the outside air let in.

Let me ask you about your label Bedroom Community. How did you come to know these people and decide to create this collective?

When I started recording in the studio and getting into production and all that, it first came from writing my own music, but I have found that I moved further and further away from myself. I was happy to step back and be the collaborator carrying other people's ideas through while having creative input, but I was also working on my own ideas all the time — producing my own experiments, discovering sounds and programming stuff. Sometimes I would write music and I would never have a place for it, or space or time or anything. But, around 2004 I started to think that I wanted to move back into my own music. I was accumulating a lot of material that I thought was worth exploring and sharing, and worth bringing people in who I've been working with on other things. I'd been bringing ideas into their music, and I thought to bring their ideas into my music.

Around that time I was half working in New York and half here [Iceland]. Björk got a place [in NY] and we did the Medúlla album mostly there, so I spent a lot of time in New York. I had a bit of time for myself and started to pull all these ideas together and see how much I had and what I wanted to do with them. At the same time I was working in the old Looking Glass Studio, which unfortunately closed down last year. It's a shame — it was a really nice place to work in. There I met this guy who was working for Phillip Glass, helping him arranging scores for film music and putting together things for performances, and he had a little studio in Looking Glass where he was doing his thing. We were working on the Medúlla album and actually we needed a piano player and somebody recommended this guy. It was Nico Muhly. We met him and we had this impossible thing to play, and he was like, "No, no, no. It's no problem," which is his general attitude with things. Nothing's impossible. We recorded with him and he just played it in two passes. He did it really quickly then moved on. Then sometime later I ran into him again at Looking Glass and we started exchanging some music and talking, and then I found out he was a composer and he was still at Julliard learning, but he was about to graduate and then he sent me a few of his things that he'd been writing. He was always apologizing for bad quality recordings because he doesn't know that, and I was an engineer and he knew a lot of the stuff I'd done before. He sent me some concert recordings with one mic on the floor somewhere, or the ceiling, or something recorded in his friends' kitchen. I wrote him back an email and said, "Yeah, I really like these pieces but I think they deserve to be recorded properly and have the right sort of production on it and I think I have the right sort of idea how to do it." We met and talked about it and he was like, "Yeah, lets do it!"

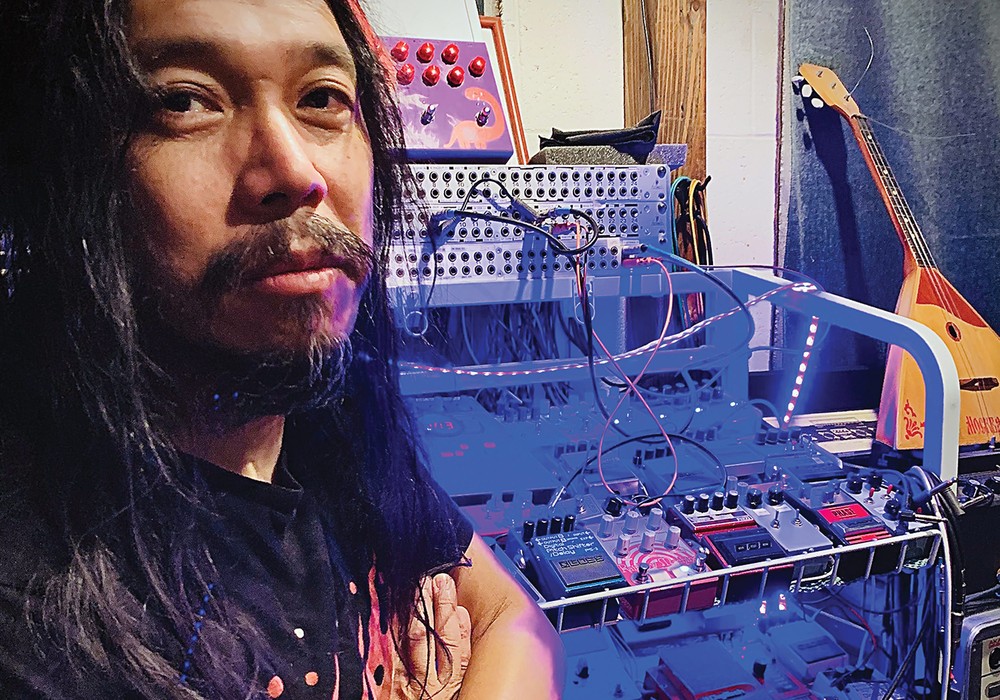

At the same time Ben Frost was here from Australia, and we had met a few years before when I went over there. He sent me his music he'd been working on and then he decided he wanted to move here after visiting again. While I was in New York he came here and he stayed at my house while he was getting settled. He stayed in the studio and was working here and he had the basic idea for the Theory of Machines record. I started thinking: "Well, here's Nico and here's Ben who has this other very different thing I wanted to participate in, and I think it's an interesting contrast with my music." There's something dialed up between the three of us. It's interesting and different enough that we could collaborate. I think if I recorded Nico's album and gave back the CD it's not going to go anywhere. Nobody's going to put it out, or give it the attention it deserves, so I thought maybe it's best to do it myself. Same with Ben's music, I thought. He was looking for a label and I thought this is great as a collective. I throw myself into this situation, and then I hooked up with distribution in the UK and it took off quite quickly. They specialized in distributing experimental type music, so they were familiar with a lot of stuff that I was involved in, and they were really excited about working with us. Then we had to think about manufacturing and artwork and all these things, so I actually think I didn't do much music for about six months. I was just setting up the label and making it work. Then the label was up and running. The idea was always to keep it small, a very close collaborative thing and being able to work on projects that I think would be hard for a label to hire me as just a producer in the studio. What we do instead is exchange a lot of ideas. They work on music I do. Nico does arrangements of strings for me, or Ben does programming. That's how the whole thing started. That gave me a platform to start my own music and gave me a kick in the behind to do it. When you keep getting asked to collaborate or work on projects that are interesting it's really hard to keep the focus on your own work. It's more fun to work with other people.

Right. Then you're in the position to say, "We have to do this this way, or go there and do it at this time," and you can run the whole thing. It's hard to do that on your own. It's the most difficult thing.

How did Nico Muhly's Mother Tongue get made? I'm coming at it with the assumption that he must have being working in Pro Tools and composing in there.

No, he wrote most of that one with a pen and paper.

Oh shit!

That was a really interesting thing. We sat down and mapped out his score into Pro Tools and started working from there. But he created his first sketches on manuscript paper, and it was almost like he created the outline, not composing every part, but then he started filling in the gaps. "This part is this many bars, then this happens, and that then leads into this and this and this." We split it into three or four movements on the record but he wrote it as one big long continuous piece without thinking about those breaks at all.

That's incredible, once you listen to the record.

It starts with the alphabet, and then it's like breakfast and morning rituals, start cooking an egg, toasting bread, putting butter on the bread and then it kind of goes from there and that's how it was mapped out. He wanted to have a sample bank of Abby Fischer's voice, who is the singer in the piece. So we have a virtual instrument with the alphabet, and all the numbers, and all kinds of things, and he played that as a keyboard part.

So the bits and pieces of his voice in the sampler were chromatically in tune so he could play it.

Exactly, so he could play it like a piano.

And with the different numbers and letters going at such a rapid pace, did different keys have different numbers or did he kind of have to trigger them?

No, there were different banks of different samples. I think each bank had two or three layers, and we had probably four different banks.

That's really enlightening. That album has such amazing dynamics and a composed feeling to it, so you assume that somebody just got a bunch of stuff and started laying it on the grid, but I don't even think you could accomplish that in that way.

I think that what he's doing is visualizing the whole piece and filling in the blanks. It's unusual.

Was that a record where you still had freedom as a mixer?

Yes. Also when we work in the studio he works so fast and has so many ideas he just throws them in and I'm editing all the time — cleaning things up and trying to keep the arrangement together. He was not cautious about anything, which is one of the great things about how we work together is that he'll just give me a lot of material and I'll just clean it up and say, "Well, I think if we only bring this in here it will be better."

So you're playing a composer roll as a mixer?

Yeah, I guess through the arrangement. When he puts all the parts in there the arrangement really comes together in the mix.

We talked about some of the stuff on the records you do being impossible to play, like on some of Björk's records and you had mentioned that you will do whatever you can to make sure that stuff sounds like its played, even if it's not possible to play. I wanted to ask about some specific examples, and one the jumps to mind is "Frosty" from Verspertine, which is that instrumental track with the bells. Is that programmed, or is that played? How did you achieve that?

Actually, that's a funny example because I didn't have anything to do with that one. But some of that stuff on that album was programmed and the MIDI files were sent to these people who make music boxes, and they basically cut holes in the disc according to the MIDI and it becomes like a mechanical play back of that MIDI track.

That explains it. That's a hard one to figure out! Are there other types of manipulations on that record where you are taking something that's electronic and making it acoustic?

Yes, some of the parts were maybe played on a keyboard then turned into a score and played. Usually you find out that, even if they seem impossible, they are usually possible somehow if somebody good enough spends time on it. But what I try and do is layer the sequence under while someone is playing, then you get a third thing that comes out. That creates a new texture that has the human thing in it and the mechanical thing in it.

Is that something you find yourself doing a lot as a practice?

Yeah, quite a lot actually.

Do you do things like adapt your MIDI back and forth from audio and line them up or do you find that that it's better to be a little loose between the two?

Well, it depends on the effect you want. But, I go in there quite a lot with a magnifying glass and make one change and then the other, to see what fits better. I'll see if the live thing works better and leave it if you can't hear the difference, but if you can hear it jumping out then I just grab the waveform and line it up.

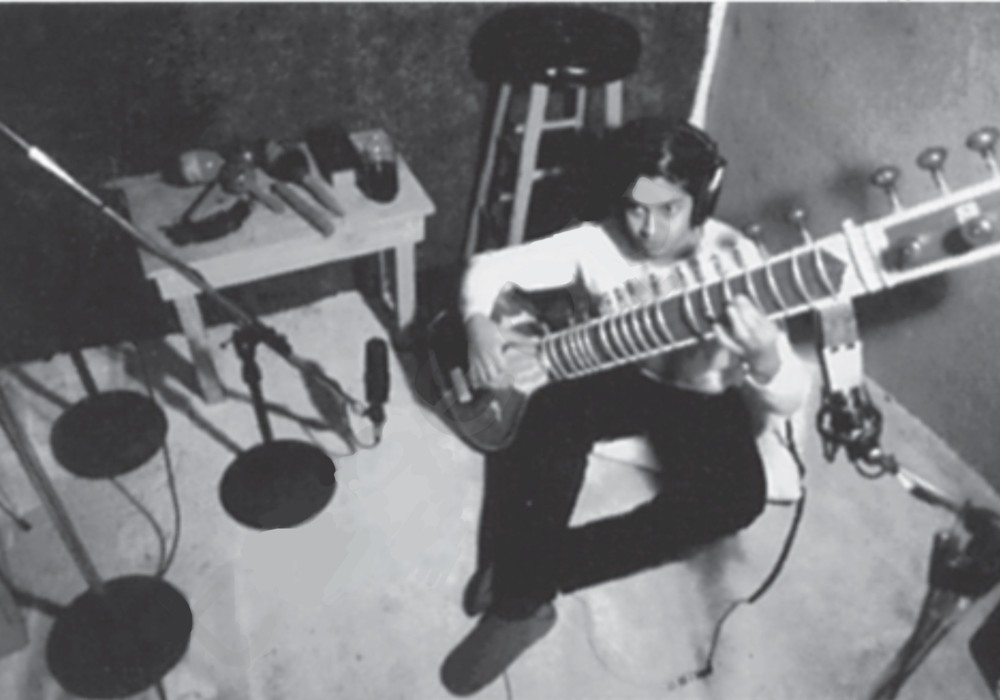

Tell me a bit about making Björk's vocal only record, Medúlla.

Yeah, she had been talking about doing more with voices for a long time and talking about working with other singers and vocalists, so the first person she brought in was the Inuit throat singer Tanya "Tagaq" Gillis. At that stage the idea was not to make a record that only had voices on it, but that idea kept developing. I guess the focus would be more on other voices, and to have a choir and have different singers, maybe have duets or other singers singing some instrumental parts. It definitely wasn't the plan in the beginning to have no instruments. We started playing all different things, programming, making beats and all that stuff that we usually did, and then we started experimenting with replacing that with vocals. A few of the songs started with her singing the chords then singing the lead on top of it, more as a guide. That's often how she writes songs, just from singing them.

I see, so she'll sing the melody on her own and then build around that.

Yeah, maybe just on top of a drone or a click track or something. Then build around that.

The intention going into that record was to make another Björk record as they had been made before?

Yes, and to just focus more on other singers.

Was there a point that you remember saying, "Okay, this is going to be an a cappella record?"

I think it was in New York when we had been around to a few different places recording, and Rahzel and Mike Patton came in to do some stuff, and around then it seemed like it was clear that we wanted to replace everything we had that was not voices, and get him to do the beats and find a voice to replace any instruments that we had. Then shortly after that we recorded the choir in Iceland.

So you were going back and forth between Iceland and New York for that record mostly?

Iceland, Brazil, Canary Islands, New York, Iceland, New York [laughs]. There were quite a lot of places.

Was there a point with that record that you felt making it into a voice was just for the sake of doing that rather then for musical reasons?

In some places that happened — "Oh this is sounding way more interesting with just voices" — but sometimes it was like going the long way around it. Especially with things like bass and frequencies that are extreme, but it was actually a good challenge because you had to find ways of processing the voice. That was allowed, we could do all kinds of editing, processing and manipulation. I think the end result was always more exciting. It took a long time just to make everything work and sit together.

Sure. How did you accomplish getting things to sit together? The potential for it to sound disparate is pretty big.

I think it's like the same thing we talked about with strings — trying to create space around each part, create the right space around it and start recording around that space. Sometimes I'd record one thing close and then another thing a little bit in the room and blend them. Because when you're recording just one thing you don't have the rest of the picture so you don't know the exact acoustical space it's going to be in, so it's good to be able to adjust it in the mix if your sound is going to be up close or you want it to be more in the room by just creating reverbs or artificial spaces. Sometimes something is just spontaneous and you just have to throw a mic up, press record and then really just have to deal with it afterwards.