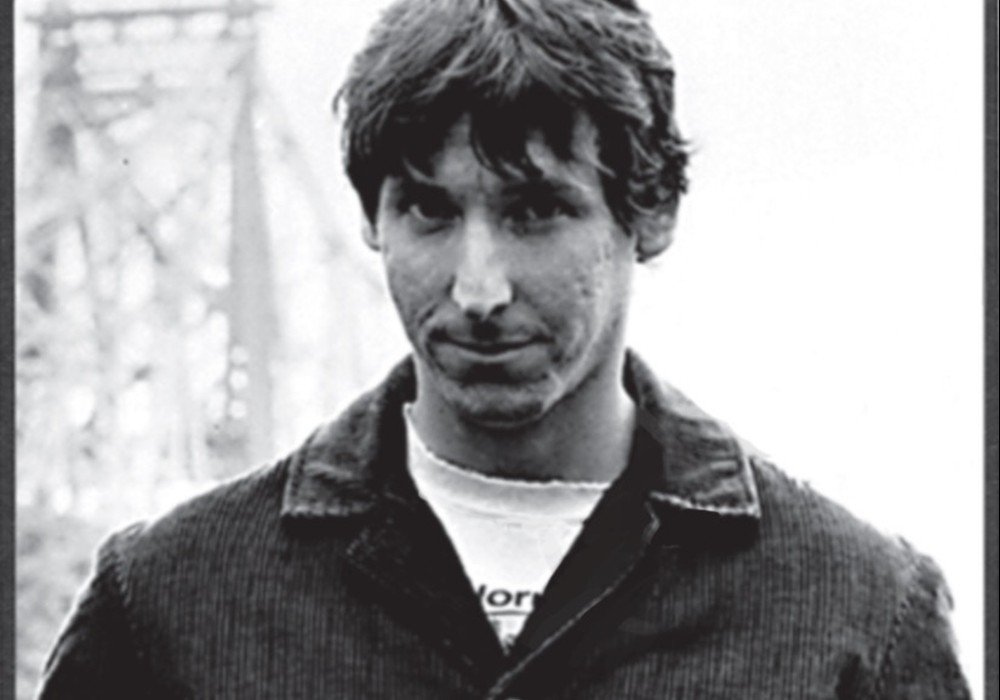

Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Public Enemy, Phish, A Tribe Called Quest, Super Furry Animals, Lou Reed, Jeff Buckley, Derek Trucks, Elvis Perkins, Bad Brains, Weezer, Ween and Wilco. These are just some of the seminal artists and bands whose music has passed through the formidable ears and brilliant mind of Chris Shaw. In his 20 years as a professional producer/mixer/engineer, he has worked on five of Rolling Stone's "500 Greatest Albums of All Time." His discography is monstrous, but anyone who has ever had the pleasure of meeting the man knows he is one of the sweetest and most unassuming gentlemen in the industry. He may have gotten far for his talents, but his lack of ego may be what defines him. With a boyish lisp and a sack full of stories, he instantly makes you feel welcome and on his level through his excitement and enthusiasm. I caught up with him in his Brooklyn apartment, exploring the life and career of the man who went from playing bass on LL Cool J's MTV Unplugged special to mixing Weezer's smash debut to becoming the man that Bob Dylan calls his engineer.

What sort of music did you listen to growing up?

My dad was a pretty good jazz pianist in Connecticut. I grew up listening to a lot of West Coast jazz — Brubeck, Bill Evans and Stan Getz. He was also a huge Oscar Peterson and Art Tatum fan. Waking up on Sunday mornings I'd hear my dad practicing, running through the Hanon exercises. My mom would be cooking, getting the sauce ready for the next meal. My mom's Italian, so on Saturday she starts the sauce for Sunday's meal. My brother was the big prog-rock fan. I used to listen to a lot of Yes, ELP and Jethro Tull. My sister was the AM radio pop girl. I had a pretty decent music collection to draw from as a kid. My brother went to MIT, and while he was there he became a music critic for the MIT newspaper.

He'd get all these advance copies on vinyl months before they were released, so I was the first kid in my neighborhood listening to punk and no wave. My brother came back to attend Columbia, and I got really into King Crimson. In '79, Robert Fripp did this record called Exposure, and that was pretty much what made me decide to become an engineer. That was the first time I'd ever heard of Frippertronics. I was learning how to play guitar at the time and badgering my brother, "How the hell is he doing that?" He pulled out a copy of Discreet Music by Brian Eno, and there's a diagram on the back with the two tape machines and the single piece of tape.

I was first introduced to Frippertronics through Phish. Did you guys ever connect on that when you worked together on The Story of the Ghost?

Trey [Anastasio] and I connected on a couple things. To be honest, I was never really a huge Phish fan. I appreciated them, but working with them was actually awesome. Great guys and monster players. On the first day in the studio with Phish, Trey's going through my CD booklet and says, "Oh my God. This is record is the greatest." I'm wondering, "What is he looking at?" He pulls out My Bloody Valentine's Loveless, which caught me by surprise. He borrowed it and I never got it back. A few months later, he sent me a new copy in the mail because he broke my copy. [laughs] But we definitely bonded over Fripp. They were working on this song called "Brian and Robert." I said to him, "Is that who I think it is?" and he said, "That is indeed who you think it is."

Who are some of your touchstone producers?

It varies from moment to moment. I really don't buy records for producers. I'm really more into the engineers, and a band's relationship with certain engineers. I think Radiohead and Nigel Godrich have a great thing going on. I'm really into mixers, however I appreciate the guys who impart a sound on a record but don't overtake what a band does. There aren't that many "true producers" left — guys who come in and radically change what a band does for the better. Brian Eno is one of those guys. There are so many bands that ask me to work with them based on other things I've done and want me to do that with them. Then you start walking down that road and they get cold feet immediately. "Ah... That's not what we do. We can't do that." I have to say, "But you asked me to do this. If you don't want to do this, then fine. We'll go halfway there and see what happens." I personally am not one of those producers. I like to work with what the band has, try to figure out where they're trying to go and push them gently that way. I'm not going to walk into an Elvis Perkins' recording session and start doing an Eno thing...

When did you make that transition from engineer to producer?

I started producing bands after Weezer (The Blue Album).

How did that one come about?

I take that back. I produced an...