John Storyk is not just a famous studio designer and architect; he's also a master of details and implementation, sharing an innate creative sense that many of his longtime clients also possess. His talent and combination of right brain-left brain attributes enabled him to quickly gain the trust of diverse clients such as Jimi Hendrix, Albert Grossman (famous Dylan manager and developer of the Bearsville complex), Alicia Keys and over 2,000 studios and institutions worldwide. Thirty-seven years in, John, along with partner and wife Beth Walters, has built a mini-architectural empire of his own, Walters Storyk Design Group (WSDG), which is truly international in flavor and diverse in its scope. While he concedes that his favorite thing is designing recording studios, he is a classical architect at heart. He wants to leave a memorable impression through physical spaces, just like his favorite architectural predecessors — people like Antoni Gaudí and Frederick Kiesler.

In building WSDG, which currently has offices in the U.S., Switzerland, Argentina and Brazil, Storyk has had a knack for choosing leaders, many of them originally his own students, to move the business forward in each region. WSDG has been built largely on Storyk's own intuition, the special management style of Beth and by delegating responsibilities to each respective regional leader (Dirk Noy in Europe, Sergio Molho in Argentina and Renato Cipirani in Brazil). WSDG maintains the same standards of excellence in all its design work around the world, but interestingly the company has evolved its own "best practice" centers that cross-pollinate. For example, the New York office of WSDG may be producing architectural drawings for a project that the Latin American office is working on, while the European office might be doing advanced acoustic modeling for a project underway in the United States.

One legacy that your name is synonymous with is Electric Lady.

I always wanted to be an architect, since I was 11 — I knew pretty early. When I was at Princeton in the sixties, I studied architecture and played in several rock and blues bands. During that year, we used to come up to the city to go to this little club in the basement of the Eighth Street Cinema, it was called the Generation. They used to have blues guys there, so we would listen to Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, the Blues Project, Al Kooper. One night, there was a funny left- handed guitar player on the stage by the name of Jimi Hendrix, who the world was just meeting in 1966. In June of '68, immediately after graduation, I moved to Manhattan and started working for a more conventional architecture firm. Two months later a very strange event occurs. One evening I noticed a Village Voice ad looking for carpenters to work for free on the construction of a new experimental nightclub. I answered it because I was kind of bored. I said to myself, "You know, that would be fun. I'm kind of handy." So I meet the club owners and in two weeks, I find myself redesigning the club — two months later we build the club on Broome and Crosby in an area that's now called SOHO.

So was this effectively your first acoustic job?

No, there weren't any acoustics on this project. I was the architect and the lead carpenter, all rolled up into one effort. We had a lot of fun and it was a lot of work. Before this, I had only designed one house, and I designed a bookcase for a friend in college. At this point I still haven't left my day job! So we build the club — $3,000, no permit — it opens, it's a huge success. It's called Cerebrum. There are floating platforms and smoke and projectors — we're way ahead of our time. It was very cool. If you came to New York, you came there. "It was the time of my life," as they say. Well, one night, Jimi Hendrix was there. Little do I know but at the same time in early '69 his manager, Michael Jeffries, decided to buy that club in the basement of the movie theater. As I'm told, I think the tab got so big that they decided to buy the club, which had been a polka dance club for 30 years before becoming the Generation. Jimi, accordingly, tells him, "I was at this club downtown — find out who designed Cerebrum so that he can design my club." So I get a call one day from Michael Jeffries' office.

How bizarre is that?

Well that's pretty bizarre at the age of 22. Would you like to design a club for Jimi Hendrix? "Well, let me check my schedule."

How confident did you feel in your abilities at that point? Did you just want to go for it?

I don't think I thought about it. They were crazy times and I honestly don't even remember. I think in reality, my wife took the call. The next thing you know, I'm having a meeting with Michael and Jimi. Their offices were on Park Avenue, and I get hired. I take a few weeks, I design Jimi's club in the evening — remember, I am still working during the days, so I do the drawings at night. I get a call one Sunday night. The presentation is Monday, "The project has been scrapped." Heartbroken. Why has it been scrapped? Because Eddie Kramer [Tape Op #24], Jimi's producer, has talked him out of the club and into a recording studio. Then he said, "You can still do the recording studio." I say, "I've never been in a recording studio." "No problem. We'll slow the project up a month." I agree to quit my job. My wife is a waitress — we figure it out. Money was different then. Eddie and Michael said, "We'll hire a young producer who could help a little bit on some of the layouts and technicalities and he'll show you some other things." That person was Phil Ramone. So I went and toured every studio that I could find. I start drawing it and I start building it — it took about a year to build it. The studio was famous even before it was one third complete, because it was Jimi's studio.

Other artist-types were doing similar things at that point, too, right?

You know, now that you go back in history — in 1969, Brian Wilson is probably building a studio in his house, and Neil Young is probably building his studio, but there was no "industry" of independent recording studios as of yet. The first great heyday of building independent studios, which was in the '70s, hadn't arrived yet, so this is fun. We're building every day, and I'm living in the Village. Of course at the same time, I'm still in the band and I'm meeting a lot of wonderful people.

Building your network.

I'm hanging out with Eddie, I'm meeting artists, I go to Woodstock in '69, I meet Albert Grossman. I met him because one of his road managers, John Taplin — specifically for The Band — was a schoolmate at Princeton. So now Albert is thinking about starting his studio and building his empire. Before Jimi Hendrix is done with his studio I get a call from Leon Russell to do his studio, Todd Rundgren is approaching me to do a studio. Paul Butterfield. I meet a lot of world class musicians. Every Friday night I am going to the Fillmore East, listening to great music. And all of a sudden it occurs to me that, although I'm an okay piano player, there's a whole different level out there as far as music is concerned. I'm seeing Elton John and all these musicians. I'm okay, but....

So you realize your limitations in one area, but find your talent emerging in another.

Yeah. The studio thing is taking off. I've got a few projects. By now, I left my job. I worked for about six months — the only time I ever worked for anybody. By the time I was 40 I still did not have time even to get my architectural license. The licensing board said, "You don't even have enough years of formal education to become a licensed architect," and I'd gone back to grad school, but never got my degree. So I say, "I've done 500 studios." I got a special meeting in Albany and they gave me work credits. I had to demonstrate my competency and get some letters, but they gave it to me.

How are things now?

Busier than it has been in years. There are always going to be studio users like Alicia Keys, who are creating custom, production-oriented studios — these kinds of facilities are driven by an artist or a group of people that have a specific use for it. There seems to be a seriously changing business model for studios being created. Most studios, such as Alicia's newly created Oven Studios, have a built-in user base. This used to be called the "project studio," except these environments are not small — in many instances very sophisticated. There are always going to be people who want to create a studio facility, purely out of the passion of doing so: kind of "if you build it, they will come." It seemed that in the '70s and '80s there was a large number of studios in this category. It seemed for many years that we would be involved in studio installations that even if they were booked for 380 days a year, they could never pay for themselves. Still today on occasion we are asked to be involved in this type of studio, kind of a vanity studio, as we would call it. There is no financial model for this type of studio.

Is most of the funding for your work via private individuals or corporate enterprises?

For me it has all been private. Like Leon Russell building a studio or Howie Schwartz Recording. Labels used to be the only ones with studios, but the birth of independent studios began with places like The Record Plant and The Hit Factory, or with artists like Jimi. This ran in counter-position with the labels in the late sixties. We have done some work with Atlantic Records, Mercury Records, Clive Davis' companies and others.

How do you evaluate what kind of jobs you take on these days? Are you more selective about who you work with in the current environment?

On average we say, "No" to two out of three inquiries. For a design project, imagine that you are going to be married to a client for a year — sometimes more! So I'm going to spend more than a few minutes to interview you. It has to be fun. It has to be worthwhile. There has to be some education. And of course there has to be some financial equation that makes sense for both of us. Getting the economics right is always difficult, but it is getting easier. Sometimes there are people who call us and know who we are, but they just don't know what studios cost. Some people are quite surprised, "I thought you were more expensive — we almost weren't going to call you!" Sometimes we are penalized for being fortunate to have good press and wonderful friends in our industry.

How has all of this work evolved? Did people just start calling you?

Well, in a most serendipitous manner during the past ten years, we went from WSDG to WSDG Europe, WSDG Latin and now WSDG Brazil, which has been around for about five years but is now beginning to take off. We are also actively developing representation in San Francisco. WSDG Latin, which is the oldest, began with a conference [I attended] in Argentina. Now we have eight full time people there.

How does the actual process differ in some of these other cultures, take the Latin culture for instance?

In the Latin culture, you need to be able to turnkey projects. We have our own contractors, eight full time construction people on the payroll in Argentina. In Brazil, we also have our own builders as well. Europe is much more like the United States, where people hire you to do the design, then construction is bid by contractors who you have relationships with. Renato [Cipriano] and Dirk [Noy] lead the Brazil and Swiss offices, respectively. They were students of mine — they became interns. I offered them jobs and they said, "Yes, but we want to go back to where we live." And that's what they did. In Europe we have five full time people. Most of our advanced acoustic modeling software is over there, because that's what they do. So now the offices are not only handling work on an obvious geographical supervision basis, but they are also now cross-pollinating. For instance, now, any intense architectural drawing comes out of this office. But any acoustic modeling for projects here, even though they have nothing to do with over there, comes out of there.

So you are drawing from their local expertise and applying it worldwide?

Yes, but we made it their expertise. We could have someone here, but it is preferable for us to utilize the skill sets of each person in each particular office. For instance, we now have a full time draughtsman working on U.S. projects, but she goes to work every day in the Buenos Aires office. If you add up the entire staff, it's almost 30 people. Each office manages themselves and is self-sufficient.

What kind of things stay the same no matter where you are?

The laws of physics are the same. But there are a few things that are different. One is that design standards are often a little different. For example, Europe is very impressed with the ITU sort of standards (International Telecommunications). So anyone in Europe is firmly embedded with ITU surround standards, whereas in the USA, these particular standards are less important. Needless to say the metric versus English measurement systems are a huge difference. The more important thing is materials. For instance in Europe, there are certain materials that are easier to get — Europe will tend to use European materials — perforated woods, a lot of slatted membrane absorbers. To be honest with you, some of the materials in Europe are more advanced. The same thing will hold true in South America. We tend to do projects using local equivalents — we will not import doors, we will make our own doors. We have brought our own materials down there to sort of reverse engineer some stuff here. So there are local considerations with respect to how you can get materials and what materials are available.

So many of these things you're actually building to specifications, like doors and other things?

Exactly, however any architectural elements are common wherever you go though. Sheetrock exists everywhere in the world, metal doorframes exist everywhere in the world, neoprene rubber, glass is available in every country made locally. It's usually the first thing we do when Beth and I visit a country we have not been to — go to the local hardware store and the local lumber yard. The woods are always different — the nature of the woods.

Has the culture of any place you worked on ever felt so distant that you thought maybe you shouldn't have taken it on, or maybe you couldn't relate?

No. There's never been a place where we couldn't get things to work. But take for instance Iceland: there's no wood! They use very little wood in the country. They have very few trees and they certainly aren't cutting them down. So, we created our studio design solution using as much lava rock as possible — it was a lot of fun and turned out to be an excellent acoustic surface treatment. In Timbaland, Tim Mosley's new studio located in Virginia, we used doors made of wood from Argentina that you can't get in this country.

Is there a favorite type of project that you like to work on? Studios, theaters, places of worship, etc.?

After 35 years of designing technical spaces, spaces that involve critical listening, I am still fascinated by audio recording environments. This past year we were fortunate to work on projects for Alicia Keys, Aerosmith, Tracy Chapman, Dave Fortman and most especially the just completed facilities for Wynton Marsalis' Jazz at Lincoln Center. We are indeed thankful.

That's something that you should be proud of from a legacy perspective.

I'm very proud of it, proud to be on the team — and it was a team effort. We partnered up with ARTEC and Viñoly Architects for this one. Fantastic effort.

Can you tell me about Firehouse 12 in New Haven?

This is a very different studio model. Nick [Lloyd], our client, is totally passionate about this place. With some family funding, he purchased an existing firehouse from the city, converted it into a combination studio and performing club — a very cool idea. Now the idea of making a club in a studio and melding them, that's been tried many times, and in my experience, has been unsuccessful. But I believe Nick will pull this off.

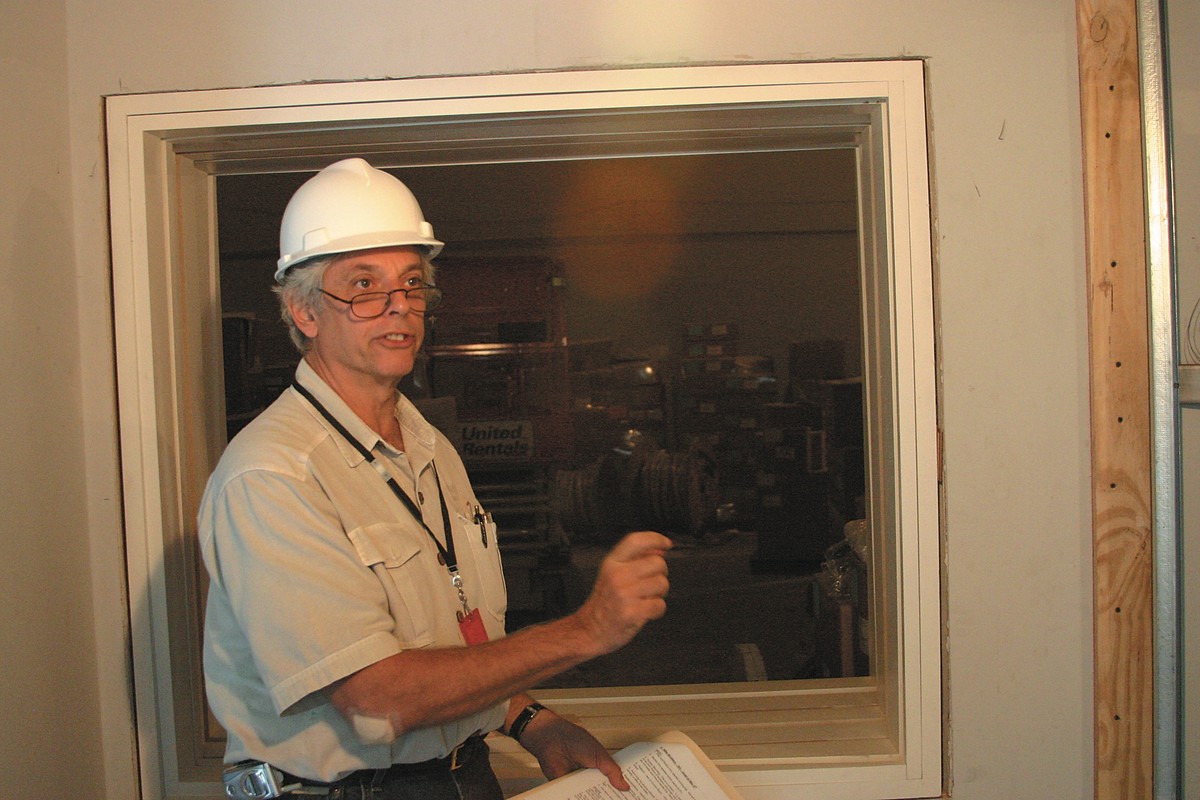

What is the building like?

He did a complete re-gut and spent over a year designing it — did a fantastic job. The studio is all vintage analog. He went and got all vintage API, Studer... just the flavor and the feel of it is great. There were very, very specific personal agendas at the design level, at the equipment level and the programming level. It's in a great section of New Haven. The owner himself graduated from Yale and he's very connected with the New Haven music scene, which is semi-substantial, with lots of clubs and musicians.

What kinds of projects do you find most appealing?

The most interesting projects are the ones where there is the highest personal signature. It doesn't mean that the Jazz at Lincoln center wasn't interesting — Jazz at Lincoln Center was amazing. The scale of it was huge — the mechanics of it were huge. But there is something kind of magical that happens when Alicia picks up the phone and asks if the stain color we have specified for the wood is going to work with the carpet that she wants. This type of personal care to attention by an owner is very unusual and a lot of fun to deal with. I like projects where the mission is interesting, there's a twist in it, and there's a personal kind of passion. One such project is TruTone mastering. Think about it. How many people wake up and say, "Hey, we're going to open up two mastering facilities for vinyl only." That in itself is a story. Total full circle

It's a boutique thing, but still clearly valued.

Their main business? It's the dance guys. That entire industry is vinyl — it sounds better! Business is booming. So while everybody else is closing, they stayed open and they grew. They built two super, very high-end audiophile rooms, except you turn around and there's all these lathes! Totally high-end. He keeps two or three extra lathes for parts and he does his own repair. The story is out of control and it is consistent with what we were talking about — the producer-driven, or niche-driven kinds of businesses. Although the owner is not a producer, he and his wife were very passionate about what it looked like and what it felt like. They were totally engaged and terrific to work with.

Did this make you want to work harder?

I wanted to work harder, and I did. Same thing with Alicia: "John I can only make it on next Saturday, can you be there?" And I'll be there. It's not the star thing. For Aerosmith, we did that project and from day one, I knew I would never be able to publicize it. I can mention it, that's about it. No pictures, no nothing. We're disappointed that we can't show pictures of our work, but sometimes this is the price of being able to do the work.

So you are always involved in the birth of these projects, but how much ongoing communication is typically required after that?

Sometimes a lot, sometimes not much. One way or another we stay in touch. This morning I got an email from Mark McKenna at Allaire telling me that the Great Room was the best room that John Leckie [Tape Op #42] ever mixed in. That's nice to hear. Sometimes you do a great job, and they don't even hire you to do the next studio. To be honest with you, I love Allaire. Randall Wallace, the owner, was a terrific client to work with — he kind of left you alone. He's a very private person who has a number of special interests such as collecting vintage guitars — plus he's an exceptional photographer. When they hired Mark [McKenna, studio manager], things got very interesting — Mark bringing a tremendous amount of studio operations experience to the picture. What happens is the projects come to an end. If I wanted projects that didn't come to an end, I would have chosen a different life, maybe operating things. I can't tell you how many times I've had opportunities to be a partner in a studio: dozens of times. I'm not an operations person. I barely can operate my own business and am lucky to have Beth and Nancy Flannery running the ship. I'm more of: In comes a dream. It's someone else's. I marry it with my dream, I do my work. One question you didn't ask me, because you're too smart to, is what my favorite studio is. My answer to that question is always the same. My favorite studio is the one I am working on right now — it has to be. There are bits and pieces of lots of studios that I still really love and they make me smile, but there are also bits and pieces of studios that I hate and wish I could do them again! I walk into a recently completed studio of mine and say, "Wow, I wish I could make this a little lower!" You know what I mean?