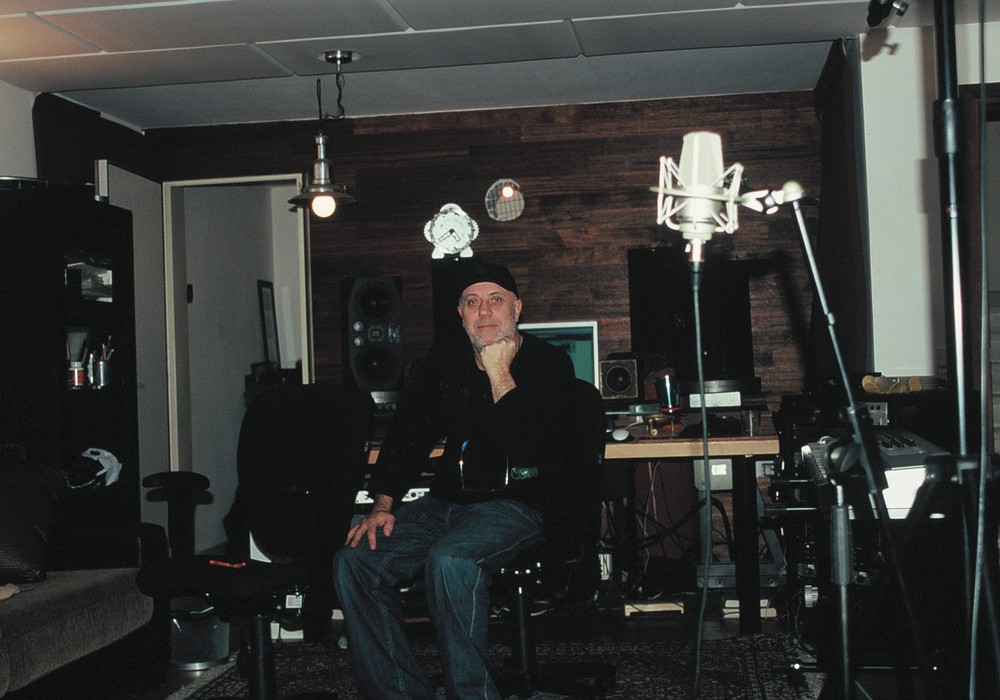

You're a producer, an artist, and a drummer – it's an interesting career path.

Yeah, I started as a drummer, and it's kind of my main instrument. But I also get antsy and want to do other things. I'm taking a drawing class starting next week, and I'm very excited. I'm terrible at drawing.

You'll get better! [laughter]

I hope so.

The most important thing I learned in art classes was to stop assuming what you think you're seeing, but rather to examine what you're really looking at and how it appears in that moment.

Yeah. I'm excited.

Whenever we bring outside influences like that into our lives, it enriches everything we do.

I always doodle, and I will draw when I'm on the phone. It's terrible, but it's fun. I'm excited to be able to use a different part of my brain and look at things differently, which I know will help with songwriting and music. I've always wanted to do this, but I was either on tour or busy, so it was hard to commit to even eight weeks.

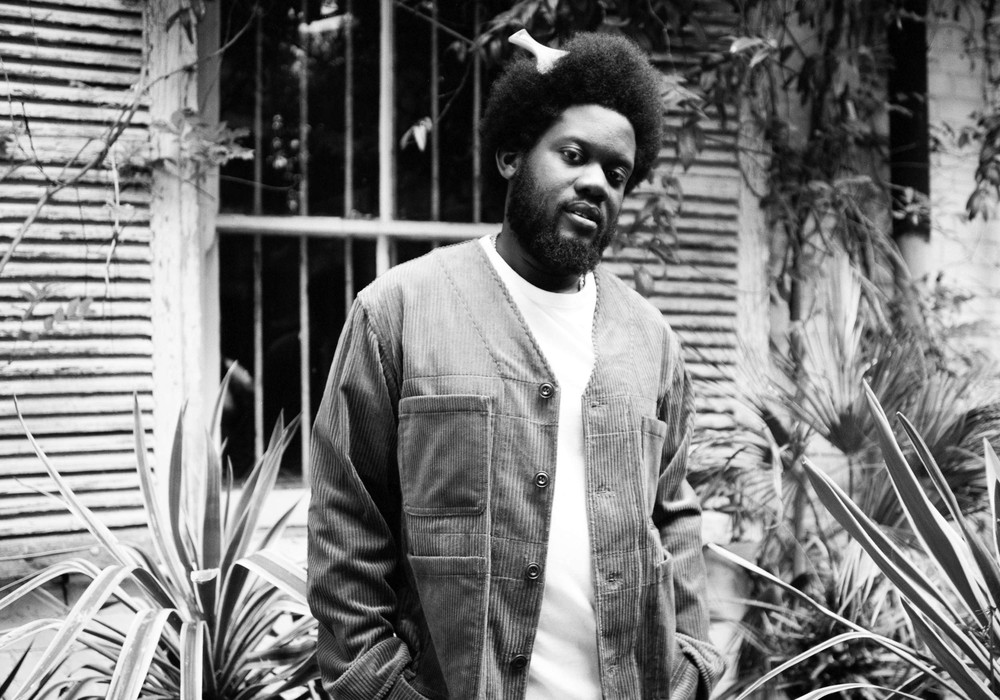

Your last main record, From Where I Started, was co-produced with my pal, John Morgan Askew (see John interview here).

I love John. We have so much fun together.

How did you two meet?

I think one of the Blitzen Trapper guys said, "You need to work with John. He's really good with female vocals." He came to one of my shows when I played in Portland, and we hit it off. Then I went down to his house, because he had all of his studio gear at his house at the time. I really liked his vibe.

Did that make John an obvious choice to engineer and mix Margo Cilker's first record, Pohorylle?

Yeah. I've pretty much always produced my own music. I have a microphone at my house, and I can get this done. I'm terrible at Pro Tools, but I can make it work. I get frustrated, but I can get the core of what I need and bring it to the band. My friend, Bart Budwig, is a musician, and he's on Fluff and Gravy Records as well. [The label Margo Cilker's also on. -Ed.] I had met him a long time ago in Idaho when we were both playing a show. He's hilarious. Before I knew who Margo was, he texted me and said, "My friend, Margo Cilker (see Margo interview here), wants you to produce her record." I was like, "What?" I had never done that for other people. I know how it works, and I have confidence in that. Taking on someone else's songs was a new experience for me. She was living in Enterprise, Oregon, at the time, and I said, "Send me some demos." She sent me some demos and we got on the phone. It was something about her energy where I was like, "Oh, I get this girl." We have a similar awkwardness, and we don't take ourselves too seriously, but we are very serious. We kept talking on the phone, and I started really listening to her demos. I thought to myself, "Oh, I totally know exactly what to do here." She said, "I want you to play drums." I was trying to figure it out, "How am I going to make this work?" To be able to take the song, put the drums on, and make sense in my brain of how this was going to work. We finally figured it out: I got my friend, Rebecca Young, an amazing bass player, to play on this. Margo came up here, and that's how we started it. I thought, "If we can get John on board, I know it's going to be amazing. If we have a good idea before we get into the studio, so we don't waste a bunch of time, we're going to nail this." John said yes, and we finally set studio time. Margo came up here months before we went in the studio, and I recorded some of our demos in the practice space with us three and that really helped me. I come from rhythm, so producing is very much the drums, the bass, and the song.

That makes sense.

I really connected with her songs. I knew that I could make sure that they didn't get overproduced; I wanted to keep them raw and beautiful. I was gaining confidence in that, but I was also terrified because I was responsible for this girl's fate.

I feel protective of her songs and especially the vocals. I want to make sure that they are front and center, and that they sound great. Margo's songs are so beautiful, lyrically, and I want that to show more than anything else. The music – the drums, the bass, and everything else – I don't want it to be too much. I had a really good team in place, and we went in as a three-piece and did the drums, and bass, and guitar. Margo did a lot of her vocals live, too. After we'd get the drums recorded, and the core of the song, I'd ask Margo, "Are you feeling good about it?" and she'd be excited. We brought in amazing musicians to fill it in. I did both of her records the same way, because that's worked out well.Before all this, when you were playing drums with Carissa's Wierd, or later bands with Ben Bridwell and Band of Horses, were you watching the studio process and thinking, "I like this. I don't like that."?

I know what sounds good. I used to play drums for my very talented friend, Patrick Park. I learned a lot from him. When we were young, a lot of the studio work we were doing was to tape. As a drummer, that's the most terrifying thing; if I screwed up then we'd have to do the whole damn thing over again. I got good at playing to click tracks. I learned early on that I loved recording, and I loved being in a studio. I thought about going to a recording school, but I never have. I get overwhelmed with so much technology. It's like, "I just want to play it!" I learned a lot when I was younger by watching people, like you said. It'd be, "Oh, I could have done that." Or, "That doesn't make sense. Don't do that." Or, "That sounds amazing." When I recorded my first record [Sera Cahoone], it's not like I wasn’t trying to be this "big musician" or something. I just wanted to record a record, I wanted to play the drums, and I wanted to do everything. That was the fun of it to me. I did okay on my first record, but I could have probably used a click track in certain times and different things like that that I've learned. But I really like the process of it, and I think I'm good at it and I'm gaining my confidence. Saying, "I'm a producer" is sometimes strange. I guess I'm a producer. I know how this thing works, I have very strong opinions, and I think they're good opinions. But I do think being a drummer and listening to so many projects has helped me in a lot of ways.

Has studio work changed the way you play drums? Like finding that less busy parts sound more elegant in the studio, or have more room to breathe?

I've definitely learned a lot about drumming and overplaying. Less is more in pretty much everything these days. There are certainly little parts where I can choose to just add the smallest fill. But now, without tape, if I go and record, I can ask, "Can you take that part out?" It's a lot easier as a drummer to ask, "Can we start over?" Or, "Can you use the one kick there instead of the two? I don't know why I did that." With my own songs, I don't like too much going on. It bothers my brain. Even drumming for people like Carissa's Wierd, there's not much in it. I love the space, and the drums were so simple. I really do believe the rhythm section is the key to a lot of songs. A lot of people get it right, but some people get it wrong. It makes a difference in how the song could have gone. With Margo, I don't think I'm the kind of producer that's saying, "We're going to rewrite all your lyrics." I didn't have to do that with her, obviously, because she's brilliant. But I tend to be more like, "Let's get to the core what we need."

Starting with a three-piece backing track is brilliant. It leaves space!

All three of us together, we just love each other. It's a good vibe. We enjoy each other, and that makes a huge difference for Margo. The first time we went in, I said, "We're going to use a click track, so start practicing to that." She said, "Okay." She is really, really sweet, and with us and John all being chill, it's a cool team to go in and have fun. And we did.

When I'm producing a songwriter I'll often hire a drummer, I'll play bass, and I'll produce like that. "Let's nail this part down so we know how to present the song."

I think that makes such a huge difference. Even when I write my songs now, and they're not done – I'll be humming something – I want to hear how the drums are going to go, because I feel it helps my brain go, "Oh, this is a song. This sounds really cool." That's how it works for me; I need to hear the rhythm. I will play my guitar and sit at my drums – hi-hat and bass drum – and make sense of what's going to happen.

Has it been a funny evolution to end up where certain songs don't have any drums, like The Flora String Sessions?

Yeah. Sometimes I'm like, "Maybe they need a shaker?" [laughter] But yeah, not everything needs drums!

Once you'd get a basic take with Margo, how would you figure out what else to overdub?

To go to her first record – because we did them similarly – she wanted her sister to come sing all the backup vocals. I trusted that they'd sung together their whole life. We brought in Jenny Conlee from The Decemberists; she was the first one to come in. I said, "Let's get all we can from her." She did accordion, piano, and a bunch of other keyboards. Everything sounded so amazing. It was almost like we didn't even need any other instruments.

She's one of my first-call musicians in Portland.

She made both of Margo's records special. I knew bringing her in on the second one that we needed her, because she has such a unique style that is perfect for Margo's music. I'm so thankful that she was on both of them. On the first record we weren't sure what was going to happen. We brought in Jenny, and then we brought in Mirabai Peart from Portland on violin – she plays with Joanna Newsom. That felt like it was all coming together. The one thing I didn't want a ton of was electric guitar, because sometimes electric guitar gets annoying. I think it can overpower the song too much.

I know what you mean.

On the first record, we were going to get someone to come play a little electric guitar, but he got sick and didn't end up coming and I think it worked out. I went into the second album a little bit surer of what would work. After overdubs, we take notepads and figure out, "Oh, this is for sure going to be in this song. We have to keep all of this." I feel lucky that the players on these records are so good that it's a no-brainer trying to figure out what to keep.

It can be a reduction process, where you decide to mute parts here and there.

Yeah, we were having that with Margo's song, "I Remember Carolina," on Valley Of Heart's Delight. We had everyone come play on it, and everyone was so amazing. We were freaking out at the talent, but it was a tough one to figure out. "How are we going to make this song work so it's not too much?" John and I were like, "Let's remix that." There was so much coming at us; that song was all over the place.

A lot of times we've got to mute parts, even if they're great.

Yeah, and start from scratch. When so many incredible musicians come and play, you want to keep everything, but unfortunately you can't. When I'm recording, I want to make sure we get everything we can in case we need it. But limiting yourself is okay too.

How do you usually approach final mixing?

With John and I, I let him take his space and go for it first. Then he'll send me a rough version and I'll take a bunch of notes. It's remotely figuring out, "Where did that thing go?" Or, "The vocals sound a little strange." We go back and forth a bunch. For the final mixing, Margo and I went to John's. I'm so particular with mixing. They make fun of me, because I have my headphones and I listen pretty loud. I don't want to miss anything. I want to make sure... I'm getting older, so I don't know how long I'm going to have this, but I can just hear things. I realize, "There's a weird sound right there. How do you not hear that?" And everyone asks, "What?" I'm not going to be happy until I can try to articulate what I need in a sound, and if I know it's not right or not perfect. I'm getting better at that: At being able to articulate, "I need more bass," or, "Where did the violin go? I remember it being here, and now it's gone." It is hard doing that remotely, because most of the time people are not in Seattle. I'll never experience it as much that way. It's important to me to make sure I get there, and we finalize it in person before we send it off. It takes a while for me. I want to make sure it's perfect before I'm done. I'll listen in my car, I'll listen on a stereo, and I'll listen somewhere else. It's making sure that I feel good signing off.

I think "the protector of the song" is the ultimate role of a producer, and that has gotten lost over the decades.

Yeah. Even overdubbing. Like, "You need tons of overdubbing of all these parts." Let's keep it simple and not overthink it. Of course, we had moments of overthinking with Margo. At times we needed to take a break, come back in, and restart. We needed to keep it fun and light; that gets the best out of her, because she is such a hard worker. It's not like she doesn't take this seriously. That was another thing that impressed me about her. She does her homework. She's not messing around. She comes across very chill, but she works hard. I respect that. Her trusting me with her songs has been rewarding, and also scary because I want to make sure she's really happy with them. That makes it very important to me. I'm so open to her opinions and thoughts, and I want to make those happen. She knows that I am on her side, and she trusts me.

That's basically the ultimate producer, Sera.

Well, I think she's like a little sister to me. We bonded immediately and I understood her. That's been the coolest thing, to watch her progress. We're both such weirdos in our own way. The music industry is so annoying in so many ways that we both feel, "We're only going to do what we want to do." When she came in to record vocals for her second record, she just nailed it. We were freaking out in the control room. That showed her confidence and skills from touring. It's been rewarding for me. It's a new direction in my career that I've enjoyed, and I feel I got pretty lucky that fate and the universe put us together. I love that she's getting attention; she deserves it.

Do you have a new solo album to write, or someone to produce coming up?

I'm working on that. I have so many songs that I need to finish. I haven't had a record for a million years, but I feel okay about it. A lot's been going on in my life since my last record. So, right now it's about taking it all in, and I feel it'll all come out. I'm in that place of, "What do I need to do to finish these freaking songs?" I have thought about working with a producer or somebody else, but I haven't taken that step yet. I don't know what is next, but if I produce more people, I feel like I'd better really like the music. I put so much heart and time into it because I want it to be really good.