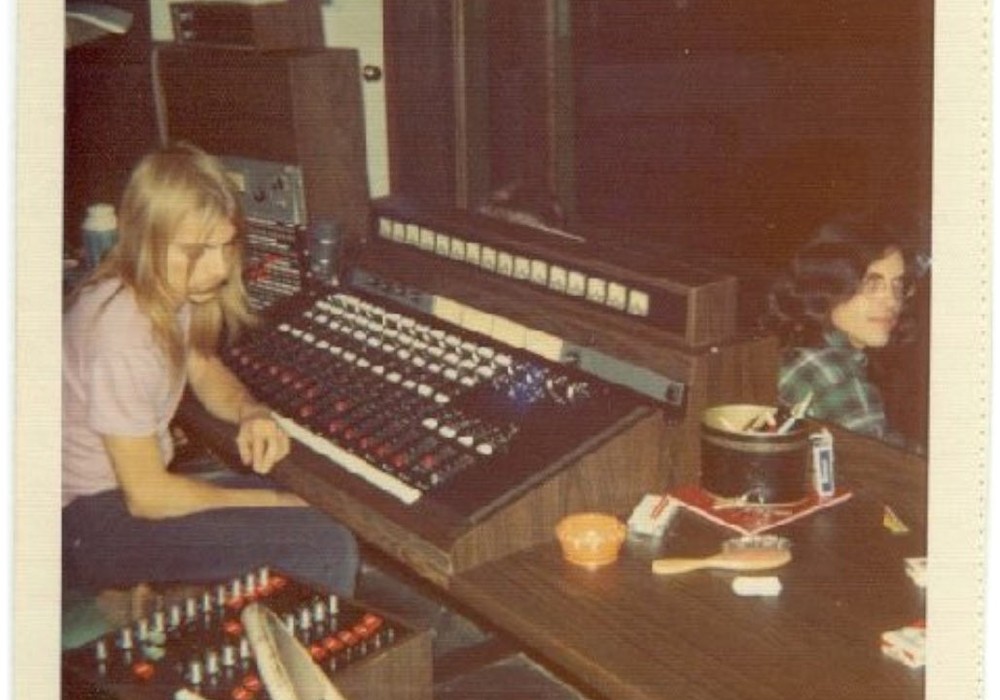

Beginning in 1974, when bands needed label attention and access to a proper studio to get their music out and heard, visionary power-pop band Shoes created their own terms – building a home studio in their living room while learning how to play music and record simultaneously. Shoes’ unique approach to songwriting and sonic identity under these circumstances have been a blueprint for bedroom pop projects everywhere for the last few decades – whether these projects know it or not. I recently got the chance to chat with founding members Jeff Murphy and Gary Klebe. They went into the history of their home-recorded process in the 1970s, recording and mixing classics albums like Black Vinyl Shoes, and what their experiences are today with all the endless options available.

What inspired you to get into home recording records like Black Vinyl Shoes?

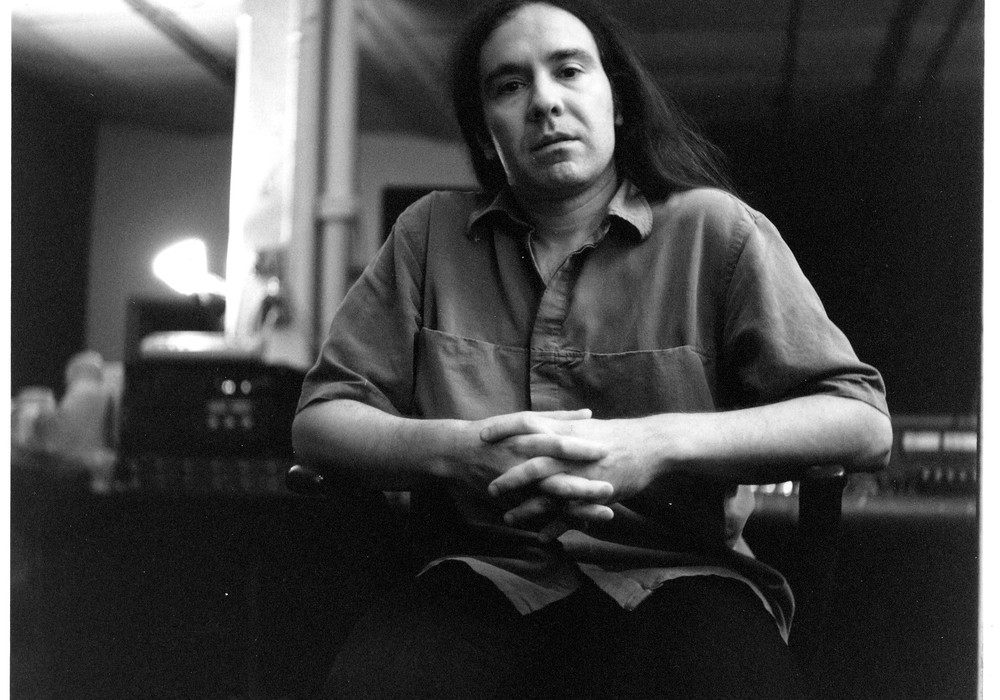

Gary Klebe: It was really through necessity. At the time, we weren’t musicians. In fact, I’m still reluctant to call myself a musician. We didn’t play live; it was a band in name only. Recording was our only way to be in music. Playing live wasn’t a realistic option. That came along later, but it was always secondary to recording. We weren’t capable of doing anything but record. There was a lot of punching in and out, and redoing. We weren’t natural virtuosos at singing or playing guitars.

Jeff Murphy: We would say to each other, “You’ve only got to get it right one time.” While we were learning how to play, we were stumbling, and it was like, “I’ve just got to get one good take that I can keep, and then we’ll move on to the next thing.” That helped us learn and mature. We’re more songwriters, arrangers, and producers than musicians. Musically, we learned to play by trying to write a song and play what we heard in our heads, which is kind of the backwards way of doing it. Most musicians learn their craft by playing first, and then later learning how to write songs. We came up the exact opposite. We were born in the studio; it was our home. Now, home recording is more the norm, with Pro Tools and other DAW software.

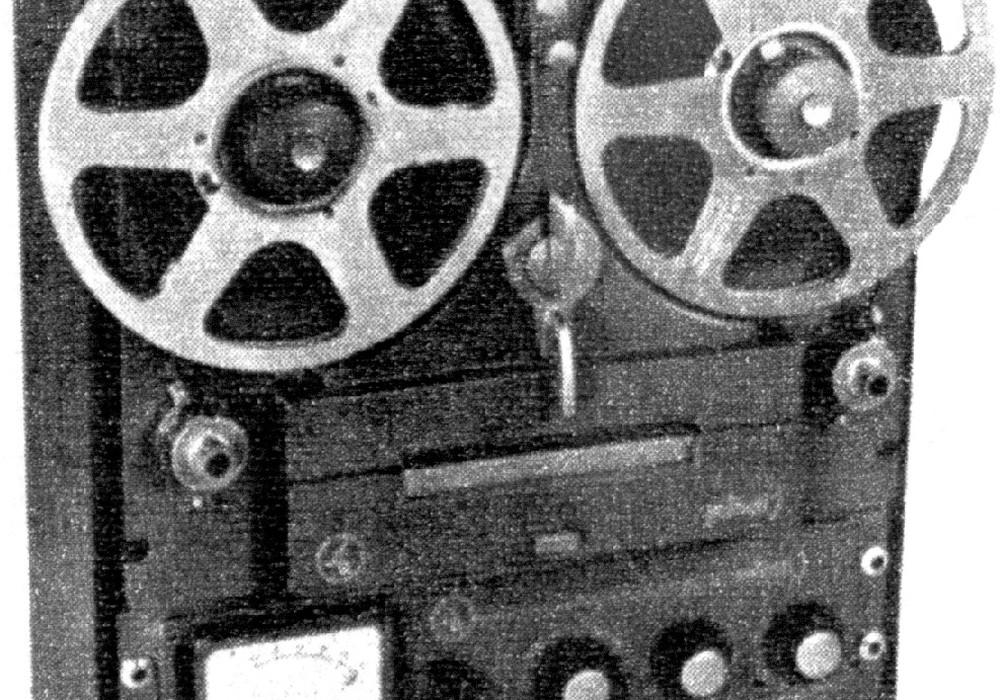

GK: Without the TEAC [A-]3340S tape machine, there’d be no band. That’s what allowed us to put our foot in the door and see if we could do this. We were very sheepish about it at the time. Anyone we knew – friends, acquaintances, or whatever – would make fun of us. “If you don’t play live, then what good are you?” We thought, “Well, you might be right, but this is all that we can do right now.”

JM: Gary and I both had stereo reel-to-reel tape machines that had the sound-on-sound function. One day, in early 1974, this friend of mine who worked at an audio store said, “Oh, you’ve gotta check out this new TEAC machine that’s coming. You can do four channels. They’ll be in time with each other, because there’s a sync switch. You can do overdubs!” Now, with Pro Tools, most people don’t realize the whole challenge of recording with the limitation of using only four channels on analog tape. With the 3340S, we could record on one track and then listen to it in sync mode while recording on another track in perfect time. Without that sync capability, we wouldn’t have been able to bounce tracks around. Recording Black Vinyl Shoes would have been impossible.

What planning did you do to make the best of the low track count availability on the TEAC deck?

GK: Jeff had a formula for it.

JM: In the very first recordings, we simply recorded one instrument directly to each of the four tracks. But then we got more sophisticated. We remembered reading about how The Beatles recorded. They would talk about making “reductions.” We called it “ping-ponging” or “bouncing.” We would record on three of the channels and then mix those together and “bounce” them down to the fourth channel as we plugged in and played along to it. Now, the fourth channel contained what was bounced from the first three channels, plus whatever additional instruments, handclaps, or background vocals that we mixed in during the bounce. Then we could go back and erase the first three channels and record new instruments on them. Using the same process, we’d continue bouncing between channels as we mixed in new instruments or vocals. It was all recorded piecemeal, bit by bit. The real challenge was that we’d have to guess in advance how loud an instrument needed to be in comparison with instruments that weren’t even recorded yet. We learned to record the bass last, because the bass guitar would get mushy if you bounced it. As we recorded the bass, we might play a tambourine or something with high frequencies, like maracas, along with it. Later on, if we thought the mix wasn’t quite right between...