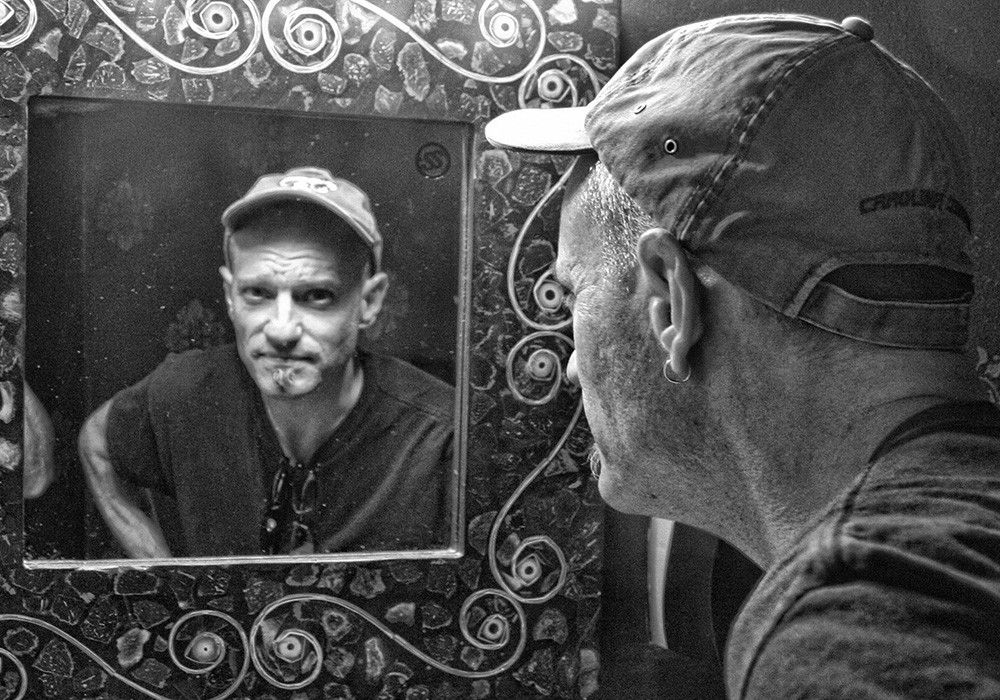

If there is anyone out there who is meant to be working in music as a producer, engineer, and songwriter that would be Toronto’s Gavin Brown. For years, he has been Canada’s go-to producer. His list of credits is long; he’s ultra-enthusiastic and spares no expense. He utilizes practically everything out there (plug-ins, gear, etc.) to make a song the best it can be. He’s worked with Metric, Barenaked Ladies, The Tragically Hip, and Three Days Grace. He’s an inspiration in the number of things he achieves in music. Recently he co-wrote and played guitar on Sting’s song, “Rushing Water.

How did you get into the music world?

My parents and my uncle are musical, so I started when I was five with piano and drum lessons. I was touring with Phleg Camp by the time I was 15 years old. So, by the time I was 20, I’d already toured the United States a few times, as well as across Canada, as a drummer. In my early 20s, I started doing more studio work and professional touring. I wound up being the kid in the corner asking questions, coming early and staying late. I was enjoying the recording process and staring at microphones and looking at compressors. Then, by my mid-to-late 20s, I had been involved in some songwriting and production. I really transitioned in when I was 27. I made it a goal to have a number one song and sell a million records within a year. For some dastardly reason, it happened.

Whom with?

It was the second single with Three Days Grace, “Just Like You.” The first song was called “I Hate Everything About You,” and that’s still their best performing song. I worked on a number of records with them over the years, as a writer and a producer.

When I talk to producers, usually they’re engineers. I’ve hardly come across one that’s also been a co-writer. Maybe Bob Ezrin [Tape Op #31]?

Yeah. There are a bunch of us. I love engineering, and I love gear. I own a ton of it, and I have my own studio. I built a new studio in 2021, getting out of my basement where I’ve been for the past two years. But I do come from this music side, originally, and I find I love the framework of song. I love the emotional part of the lyrics, and I believe that for me I can’t do a good job producing a record unless I know what the songs are, and I know what the words are.

Absolutely. It seems you like to get fully immersed.

The sonic choices and the textures, even all the minutia – like little EQs, filters on keyboards, instrumentation, and arrangement – they’re driven by song. It’s always been that way for me, as a drummer. My drum mentor, Jim Blackley, told me the first lesson I had with him – I was 20 and had already taken lessons for 15 years – he said, “Be able to learn all the lyrics and sing all the songs. You’re playing drums, but you’re playing drums in a musical context.” That transferred into producing. I love hi-hats; they’re my favorite instrument, but it’s not what the folks at home are listening to. I want them to sing along, and I like to have people interested in the music with whatever artist I’m making it with. That’s been the majority of the approach that I take; it’s the song. I don’t write everything I produce, but definitely in certain bands I’m very active in the collaborative part of songwriting. There’s a band I did at the same time in the early 2000s called Billy Talent, and I did no co-writing. Both of those bands came out at the same time. I did a lot of arrangement, and it was song-based, but Ian [D’Sa, guitar] would come to the table with seven parts for a song that needed three. I helped him choose the parts that worked well together; we focused in and got them sorted. There’s a lot of sorting that goes on when there are creative people and they have 100 ideas. They often think all 100 of them are spectacular.

Editing is difficult.

Yeah. I was lucky enough to meet Quincy Jones and hang out with him at his house one day, maybe five years ago. I was there for several hours. He told a story that I heard before about Thriller, and how they’d have hundreds of songs. They’d record ten of them and throw six of them away, and then they’d get 200 more songs. The story’s grown over the years, but I believe it to be true. There are entire records that have been made by artists and put away...