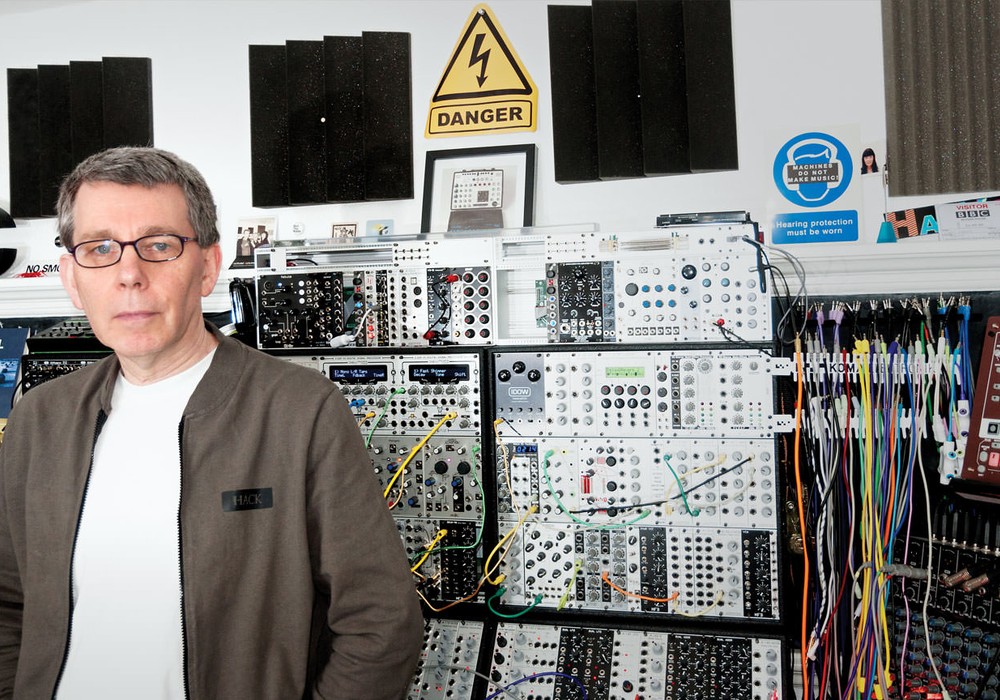

North London-born Chris Carter has had an extraordinary 50-year career in music. While working as a visual artist and sound engineer for various television stations in England, he extended his fascination for audio technology and theory by building his own synthesisers. Acting as lead synthesist, Carter teamed-up with performance artists Cosey Fanni Tutti, Genesis P-Orridge, and Peter Christopherson in the mid-'70s to form the pioneering group Throbbing Gristle – a seminal band of the industrial music genre. TG had dissolved by 1981, enabling Carter to focus on crafting radical solo works and collaborations with partner Cosey Fanni Tutti as Chris & Cosey. More recently, Carter has re-indulged his fascination for the principles of circuit bending, creating The Dirty Carter Experimental Sound Generating Instrument and the TG ONE Eurorack module. Meanwhile, the release of Chemistry Lessons Volume 1 – an album of immersive ambient landscapes, is a timely reaffirmation of Carter's compelling talent for sound design.

Did working as a sound engineer spark your interest in music, or did your passion predate that?

My interest in music predated that by quite a lot – it probably goes back to when I was 10 or 11. My dad was a hi-fi buff and was always listening to music. He had a reel-to-reel tape recorder and would make, what I suppose we'd now call, mix tapes. One birthday he bought me a small battery-powered tape recorder and a kit for making crystal radios and oscillators, so there was this mixture of listening to crooners on his hi-fi, as well as doing all these experimental circuits. When I was about to leave school, I was offered an apprenticeship as a sound engineer, then things started to overlap.

What were you actively doing during your apprenticeship?

I was working with a freelance film and television sound engineer named Ted Ball. I did some television shows and documentaries at Elstree and Pinewood film studios. I guess it's where I learned my craft. The first thing I had to do was learn how to use a Nagra tape recorder, so I was thrown in the deep end, but it was a step in the right direction and it picqued my interest working with professional sound. When Ted retired, I went off on a tangent and worked for a photographer in Soho. From doing sound for television and film to working in a darkroom was quite a career change.

What did you learn during that period with Ball that initiated your desire to experiment further with sound?

That period overlapped with me building my own circuits. I used to buy a magazine called Practical Electronics religiously and was always tinkering with the little circuits they had in there before getting more ambitious and building bigger ones. One month, they put a whole synthesiser design in the magazine, where you could build the filters and oscillators module-by-module. I started building my first synth around that period, but because I was also splicing tape for television and film as an assistant sound recorder, I was working with these two different disciplines simultaneously. Then I started incorporating what I'd learned into what I was doing at home with my own music. I'd record experiments with my synths and circuits onto cassette, because I couldn't afford to have a Nagra tape recorder at home.

How rudimentary was this synth you built? Was it akin to the Eurorack modules that we see today?

It was very similar. They would publish a different module each month, but the idea was that you'd put this thing into one big cabinet, most likely based on a bigger version of an EMS VCS3. Each month, they'd publish a part of that design, so you'd build a VCF [voltage controlled filter] one month, a VCO [voltage controlled oscillator] the next, and then a modulator. I was building all these circuits and putting them into quite a big case. This was in the mid-'70s, around the same time I met Cosey Fanni Tutti and Genesis P. Orridge, so I took my creation down to their studio in Hackney, plugged it into the PA, and we started jamming.

Presumably there were synthesisers on the market at the time, but well out of your reach financially?

I wasn't earning much, but I used to collect all the Moog and EMS catalogues and I'd actually been down to EMS in Putney a few times. At one point, when I lived in North London, I got an EMS VCS3 on hire purchase, but couldn't afford to keep up the payments. The only alternative was to build my own, so it was born out of necessity. A lot of what we used when we were in Throbbing Gristle was built by me or friends of ours – even the PA was handmade.

At that early point, did you foresee electronic instruments initiating a musical revolution?

I don't know if we were that forward-thinking. It was obviously happening; synths were appearing all over the place, but it wasn't new to us. Disco really embraced the synthesiser and electronic sounds, so we went along with that. As we got more successful,...