“If somebody’s too neurotic, I’m out. I think music is supposed to be fun, reactionary, and impulsive.”

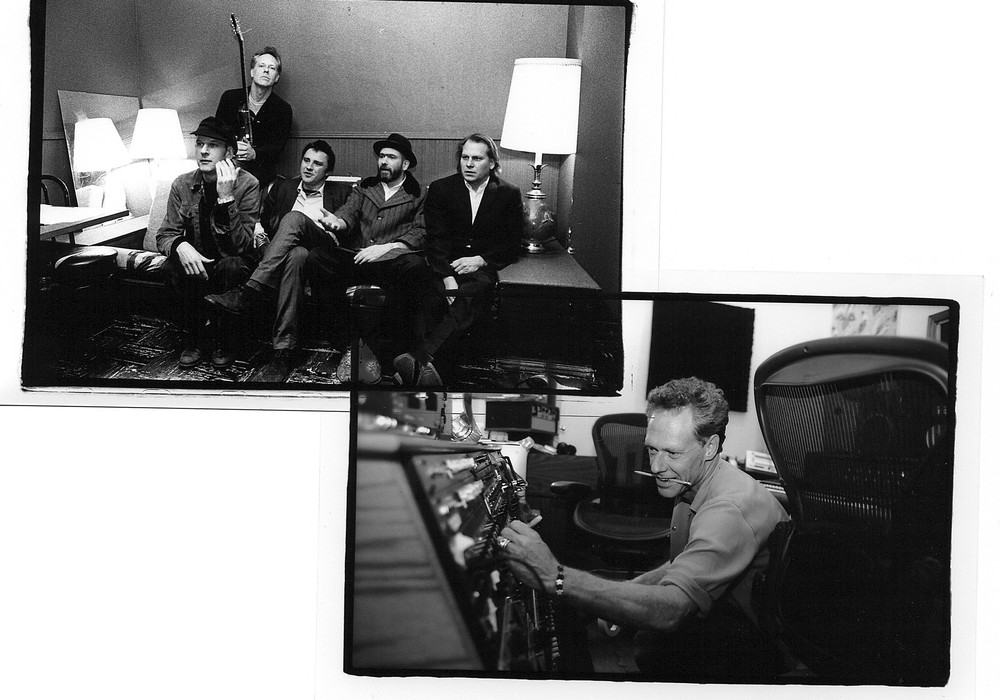

Dave Cobb’s great record production for Chris Stapleton, Jason Isbell, Sturgill Simpson, The Secret Sisters, Brent Cobb (his cousin), the Zac Brown Band, Rival Sons, Shooter Jennings, and many others have been both artistic and commercial successes. A student of historic recordings, as well as an equipment connoisseur, his minimalist real-time approach alongside such stellar engineers as Vance Powell [Tape Op #82] and Matt Ross-Spang [Tape Op #117] helps right the crucial relationship between singer and track. It was a joy to get to converse with Dave, first in his Helios-equipped home studio and again in Nashville’s RCA Studio A, built for Chet Atkins in 1965 – the perfect venue for this accomplished, brilliant, and unassuming gentleman.

AH: Why did you move to Nashville?

This town is the most amazing, supportive community I’ve ever been in. You can make phone calls, and in five minutes literally everybody shows up. I’m from Savannah, Georgia, but I lived in Los Angeles for 11 years before moving here. Every time you meet somebody in L.A., the first thing out of their mouth is, “So, what do you do?” It’s never because they want to be your friend, but because they want to further their career. Coming here was the exact opposite. I think this is the only place in the world where art meets commerce. In L.A. I saw the studios go down one by one, the labels move out, and the industry really shrink and die. In New York they were writing checks, but there were no studios in New York. I think this is the only place [where] it’s viable to be an artist, have a career, and not die. Besides country music, there’s a great rock scene, as well as Americana and folk. It feels alive. I’m not old enough to remember London in the ‘60s, or California in the early ‘70s, but it feels like that environment here now. It feels as exciting.

HTK: I read an article that said

you played on almost everything you produce.

Yeah. There was a guy, Jimmy Miller, who I love. Jimmy produced the best Rolling Stones records; Exile on Main St., Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers – he did all these records. Those records had a groove – a swagger. That’s because Jimmy Miller was a drummer. He’d get in there and play drums, or play shakers with the band. He always seemed to find the pocket. I completely rip him off as much as possible. When a band’s playing, I’ll play something, whether it’s guitar, or percussion, or bass – just something. I wind up playing on a lot of records strictly as a metronome.

AH: Do you do that live with the band?

Yeah, I hate cutting separately. I can’t stand it. It obviously works really well for a lot of people. One thing I really try to do is keep all live tracking vocals. Even if the band nailed it, I’ll keep cutting takes just to get the singer’s performance.

HTK: So the whole record’s live?

Almost every record I do has live vocals. If the singer’s singing live and they go for it, the guitar player will come down in volume when they’re singing. When they’re not singing, they come up. I think when I get to mix, I don’t have to mix as much. They self-balance. I noticed I can create the perfect track; then, when I bring the singer in, it’s hard to make it sit in the mix. But if you let people in the room mix it themselves – as they play and work out their dynamics – it’s almost like cheating. It takes a little longer going down, but it saves a lot of time later. I can’t punch it in. It won’t sound natural.

HTK: The drums on Sturgill Simpson’s Metamodern Sounds in Country Music are magical.

It’s the drummer; the way he plays. I met Miles Miller when he was a kid – just 16. We’ve been force-feeding him records, like Hal Blaine and Richie Albright – who played with Waylon Jennings. If you hear the tuning on the drums it sounds so terrible and goofy, but he’s just barely hitting them. It sounds big because he’s barely hitting. If somebody hits hard, things collapse.

MR: A lot of people think John Bonham was just pounding away.

He wasn’t. I got to make a record with his son, Jason Bonham – and Glenn Hughes from Deep Purple – about a year and a half ago. He came in here and sounded like those records. He’d grown up playing with his dad; he hit medium, but he wasn’t killing the drums. He said his dad’s favorite drummer was Mick Fleetwood, which I never would think. His dad would say, “Listen to that,” to a really basic thing. “Listen to that groove. That pocket. That’s what it’s about.”...

_display_horizontal.jpg)