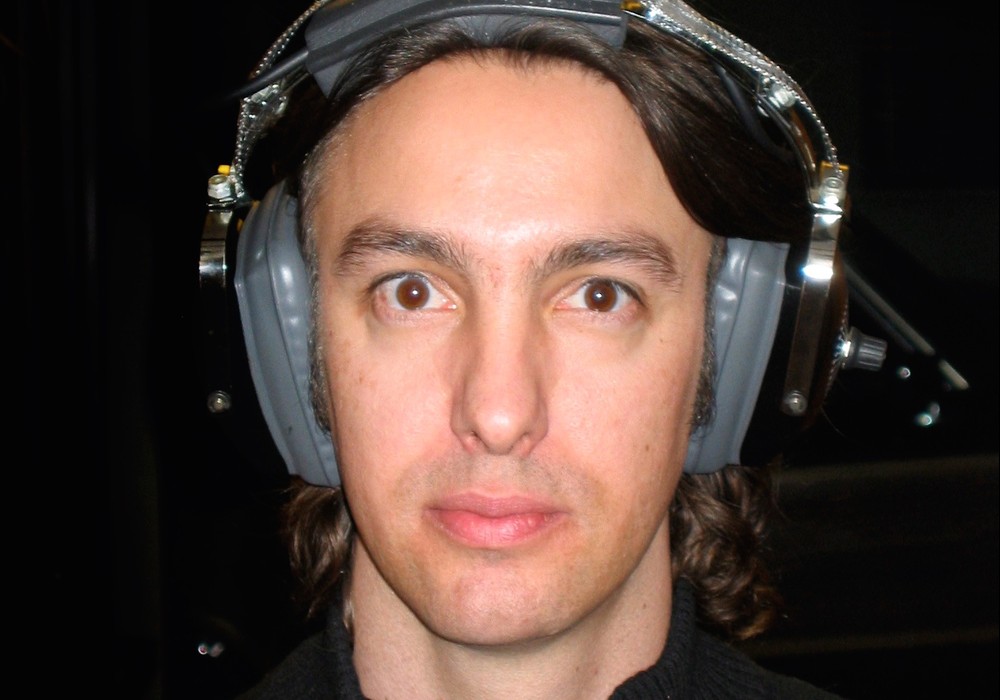

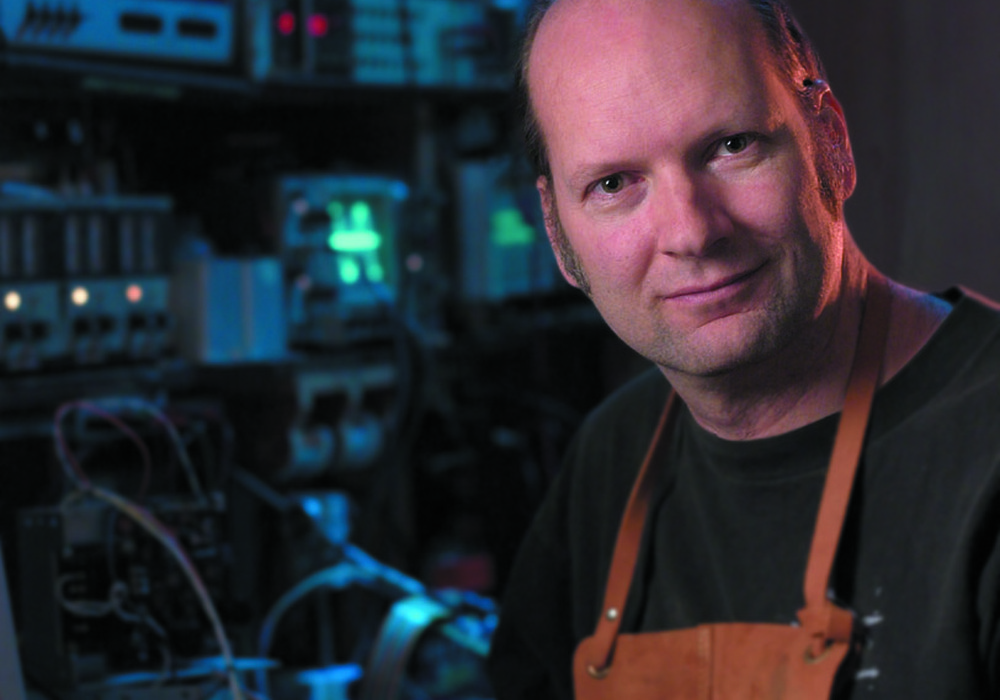

You might not know Brian Reitzell's name, but you probably know his work. As the music supervisor and composer for most of Sofia Coppola's films, he's worked with the French electronic duo Air on The Virgin Suicides, coaxed My Bloody Valentine's Kevin Shields out of retirement for Lost in Translation, and placed Frank Ocean and Kanye West alongside Can and Sleigh Bells for The Bling Ring. He's also composed scores for other films, television, and video games that showcase his formidable skills as a performer and arranger of evocative (and frequently unidentifiable) sounds. Amid the ruins of a collapsing industry, Brian is the rare musician who's found a way to thrive, and to do it by making and curating music that isn't bound to pop or Hollywood conventions.

Brian began his musical career as a drummer, playing for the mischievous grunge-wavers Redd Kross, and later for Air, with whom he worked on their album 10,000 Hz Legend. He's kept these collaborations going through much of his film and television work, often sharing credit with handpicked collaborators: he scored Friday Night Lights with Texan post-rockers Explosions in the Sky and Stranger than Fiction with Spoon's Britt Daniel. He also released the first new music from Talk Talk's Mark Hollis in more than 15 years as part of the score for the Gus Van Sant produced TV serial Boss. Most recently, Brian's been scoring NBC's baroque cannibal melodrama Hannibal, which he's turned into an experiment in frightening sonic textures, including bullroarers, bowed percussion, and a bizarre synth called the Swarmatron. His 2014 album, Auto Music, is a great example of corralling different players and setting mood as well.

Entering Brian's studio, in a converted apartment building north of Los Angeles' Griffith Park, is a little like visiting a Solaris-model space station. Towers of analog outboard gear seem at home beside a dismantled upright piano; an adjoining room is piled with stacks of cymbals and ancient-looking bronze percussion. There are days when he enters and leaves in the dark. The studio is equipped for a hermetic existence, with a well-stocked fridge and shelves lined with books and films, one of which is usually playing on the big screen above his mixing desk when he's not tracking to picture. When I visited, Brian started the day by playing Toru Takemitsu's mind-bending score for Rikyu through his surround sound monitors. "There," he said. "What else do you want from music?"

Your studio is on fire. You can save three pieces of gear. What are they?

Ha! Well, honestly, my red Noble & Cooley snare drum, which I bought when I was 20. I had to borrow money to get it, and I slept with it in my bed for like a month. It's been so good to me, for so long. Then there's a cymbal I have that belonged to Paul Humphrey, who played with Charles Mingus, Dusty Springfield, and Joe Cocker. It's a Zildjian from the 1940s, I think, and it sounds like no other cymbal I've ever heard in my life.

What's it like?

When you hit every other cymbal, there's always a fundamental note, an overall tone, that's kind of there, regardless of how hard you hit it. But with this cymbal, every time you attack it, the fundamental is slightly different. It's the most living-sounding piece of metal I've ever heard in my life. It can be the funkiest ride cymbal bell or the most wonderful white noise wash, all at once. The third object would be my Linn LM-1 drum machine. It's a monster. They only made 500 of them, and I have number 40. I'd have to save it.

You've answered this from a museum's point of view. Maybe I should have said that you have to make a record tomorrow.

That's a very different question! If I had to make a record tomorrow and I could only use three pieces of gear — from here? And only those pieces?

Well, not necessarily, but the things that would be most important for you to make the sounds you wanted to be able to make.

Well, again, it would probably all be instruments, because as much as I love technology, I think all that stuff is replaceable. Or, if you lose it, maybe you're not meant to use it anymore. I try not to be too reliant on any one effect, one sound, or one process — or I'm screwed, you know? Though if I could leave here with my Trident Fleximix console, my Nagra 2-track, and one of my Neumann mics, then I guess I could actually do the record.

How did you learn to listen to music?

As a kid I used to fall asleep to music every night. I took the heads off a bass drum and I mounted two car stereo speakers inside. I put my pillow inside of that so I could sleep with this stereo image above me.

How old were you then?

Twelve.

What were you listening to?

Led Zeppelin, Queen, Black Sabbath, and my parents' records... The Beatles, Moody Blues' Days of Future Passed; the one they did with the London Symphony Orchestra. The Who's Tommy was the first record I remember really loving.

Do you remember what drew you to it?

Well, come on; it was "Pinball Wizard." And the artwork. I didn't see the movie until much later, and I didn't like it as much. The stories are actually quite appealing to kids, with the wacky uncle and cousin Kevin; all that stuff was really funny to me. It was way more interesting than, you know, The Jungle Book. Which I love — don't get me wrong!

A lot of the music I loved as a young teenager had a frightening, but alluring, quality to it. Like Pink Floyd; their music hints at a spooky world of drugs, depression, and violence, but it's almost never explicit.

I think children are very enticed by dark, seedy things they don't really understand — but they know there's an energy there.

Speaking of darkness, you've made a lot of scary music, certainly for Hannibal, which you're doing now, as well as for 30 Days of Night. What makes music scary?

I don't think we get really scared all that often in our lives, but when it happens it's such a rush. There are a lot of ways to do that with sound. Sheer volume can be scary — of anything, even the prettiest chord — because it's so physical. There are high-pitched sounds that hurt. And there are sounds that create an image in your mind of something...