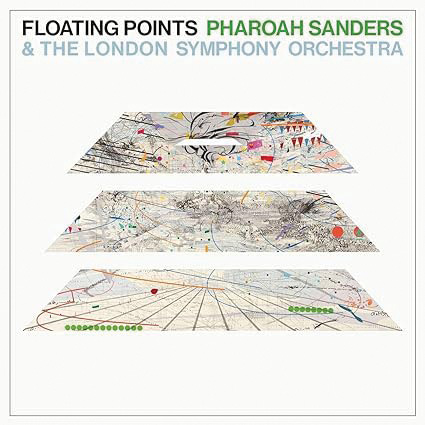

I’ve been fairly obsessed with Promises, an album by Floating Points, Pharoah Sanders, and the London Symphony Orchestra that came out in 2021. Maybe "obsessed" is a strong word, but I put it on at least once every few weeks or so and have resisted filing the LP away with the rest of my records, leaving it at the front of the pile on the floor so I’m reminded daily that it exists. It’s a beautiful and unique piece of music, one I’ve heard several people describe as "transcendent."

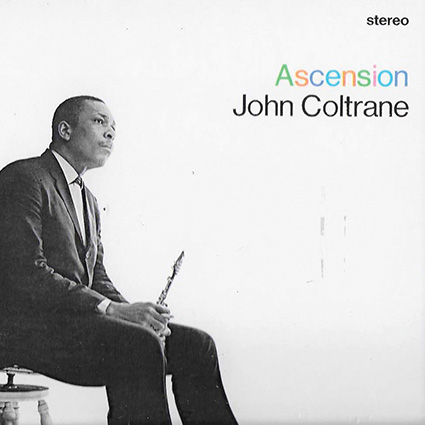

I like jazz, but I’m a bit naive about it. I have my favorites, and the 30 or 40 jazz LPs I rotate between regularly are heavy on iconic artists like John Coltrane and Miles Davis. Those two performers alone have so many albums that I have not fully explored all of their catalogs, and my knowledge of many others in the genre gets sketchy and slim fast. Because of Promises, I’ve been digging into more of Pharoah Sanders’ back catalog. I probably already knew this, but I soon realized that he had played with Coltrane, and I began to revisit some of those records he played on with a new perspective.

To tell this story, I’ll need to change the subject for a moment. In the mid-'90s I owned a studio but was not actively working as an engineer; we had several slightly younger engineers working there while I managed it. I was a bit burnt out after a decade of long days in the studio with very few breaks. I had rediscovered skateboarding, was publishing a magazine (Heckler) centered around skating and snowboarding, and I was learning about the magazine publishing world. I still booked sessions for my studio and answered our landline when it rang. (This was before cell phones or the internet took over, and when studios still had ads in the yellow pages!) One day the phone rang, and a man with a thick Dutch accent politely asked if we had a good microphone for recording saxophone. I told him that we had several (two really, a Neumann U 67 and an RCA 77-DX). However, I mentioned that "good" is subjective and that he may or may not like them. He seemed nice enough, and after chatting a bit and realizing that I couldn’t truthfully answer his question, I suggested he come visit the studio on an off day so he could record his sax into both of our good microphones and decide if he liked either one of them. He showed up, ended up liking the RCA, and then said he wanted to book some time to record a jazz record. I found him to be a nice guy and very charming, so even though I wasn’t doing any sessions at that point, I booked the time he wanted (every Thursday night, from 6 to 9 p.m. for about a month) and told him that maybe I would see him then, or that possibly one of the other engineers would be there. I thought about it for a few minutes after he left, and then called my wife, Maria, and told her I wouldn’t be home on Thursday nights for a few weeks. More than anything else, I liked this guy even though I’d just met him. The younger engineers at the studio were into Tool, Helmet, and Smashing Pumpkins [Tape Op #115], and I felt maybe they wouldn’t be into this session, or perhaps not treat him with the level of respect I was hoping he’d receive. We used to refer to out-of-the-blue sessions like this as "yellow page" sessions, and we never knew we they were going to get. I figured, "I like jazz. I like this guy. Why not do the session?" I recorded him and his five-piece band every Thursday night, and ended up with over 12 hours of finished music. Some of it was multitracked, but as I got more comfortable with setting them up each night – and realized how much music we were ending up with – I started tracking them live to 2-track. The client didn't seem that particular about the mixes, so I figured if I was going to likely mix it myself, I might as well mix it live. There was a friend of his at many of the sessions who was not really producing, but he was clearly very familiar with the music and was a good sounding board to have in the control room. I enjoyed having him there, and we would chat in between takes. After several sessions, I told him I was enjoying the music and that I thought the client was a very good player. He looked at me kind of funny, and asked if I knew of him before the sessions. "No," I replied. He then explained to me that our client was a fairly well-known player in the jazz world. (Forgive the editorial mystery here, but as I was totally naive at the time I’m trying to write this from that perspective.)

The saxophone player was John Tchicai, considered one of the leading figures in the free jazz movement, and he'd played on quite a few seminal recordings, including John Coltrane’s Ascension. John was currently teaching nearby at University of California, Davis, as an artist in residence at the time, and besides his wife, Margriet Naber, on keyboards, the rest of the band were his students.

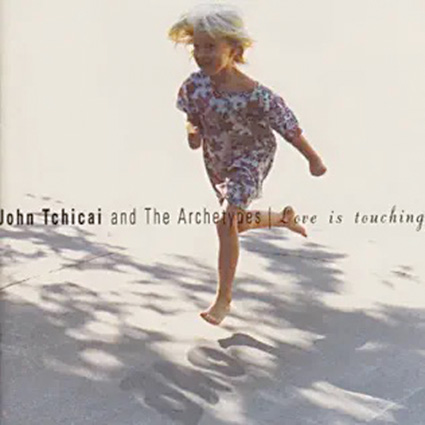

Back to the present: While I was browsing through Pharoah Sanders' discography, I came across Ascension and thought, "I need to relisten to this." Then I had a slight epiphany; John Tchicai played on Ascension, and riffing off the "six degrees of separation" trope, it dawned on me that I had one degree of separation from Pharoah Sanders. If I thought about it further, I could lump John Coltrane, engineer Rudy Van Gelder, and even Yoko Ono and John Lennon (who Tchicai had also performed with) in there too. But somehow the Pharoah Sanders connection felt special and deeper in some way, with all the time I’d spent listening to Promises and now being reminded of the sessions with John nearly 30 years ago. I found the LP I did with John, Love is Touching, streaming on Tidal. I gave it a listen, and it held up fairly well. At least I was not overly embarrassed by my own engineering! Some of it sounds pretty good to my 30-years-older self, while some of it sounds a bit dated, but I can only give John credit for being open to trying some different styles that his much younger bandmates were probably into.

It felt good, in a positive affirmative way, to make the connection between Pharoah Sanders, John Tchicai, and myself as part of the webs and links in their lives as they created their music. Besides the RCA 77 (which I still have) I can’t remember much about the gear I used on those sessions, but I do have fond memories of the time I spent with John in the studio recording, as well as later mixing, editing, compiling, and just talking. We stayed in touch for a bit, and I saw him and the band perform live a few times as well.

In the end, the gear we use and the sounds we get as engineers are not that significant, nor always that memorable. Sure, it’s fun having cool gear and getting good sounds, but I think it’s the relationships we develop in the studio that really matter. In some small way, we feel more deeply connected to culture and humanity in general, in a positive way, and that’s one of the best rewards this job can offer.