It's the mid-60s and tubes are glowing hot in studios from 30th Street to Abbey Road. Wheels are in motion and the legacy of Leonard Chess and Sam Phillips is welling up in the ears of America. In Detroit, Berry Gordy is alchemizing the collective genius of Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson, James Jamerson, Benny Benjamin and a host of others with his own, to forge a juggernaut of sonic power and consistency equal to anything before or since. It swings like a motherfucker and it sounds like gold. The staff and musicians work hard, doing takes over and over until they get them right. They try multiple mixes and follow them all the way to acetate before deciding on a winner. In the mastering room, Bob Olhsson is cutting vinyl on "Signed, Sealed, Delivered", another fluid combination of muscle and sweetness that jumps off the needle. It will hit #1 on the R&B charts. This is Motown and it is beautiful.

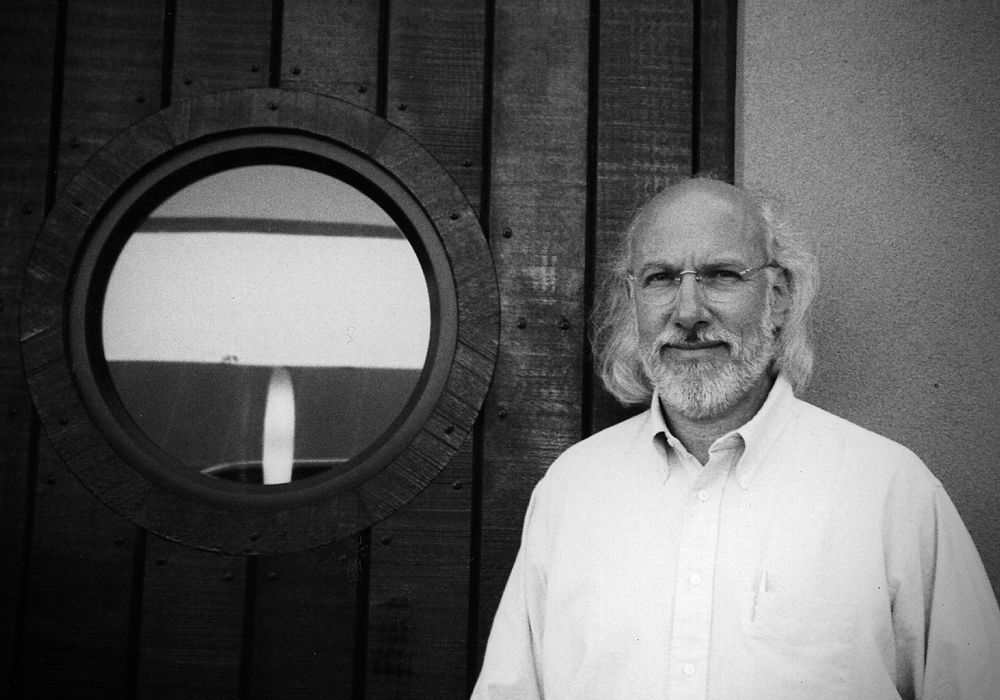

Recently Bob moved to Nashville and he's excited. Astoundingly, after working with some of the most talented people of his generation, Bob is still optimistic and hopeful about the future of aesthetics in the labyrinthine, difficult world that is popular music. He's still working, and poetically enough, he's even starting to cut vinyl again. He is disarming, friendly, and generous with his time. There's no hint of professional jealousy or egoism. Most mysteries can never be looked into; they fade into hearsay and rhetorical inventions. Talking with Bob, I felt lucky that he's not about those vain distortions.

He reflects on things too clearly. He's our window.

Can we start with how you got to Motown and what you knew before you got there?

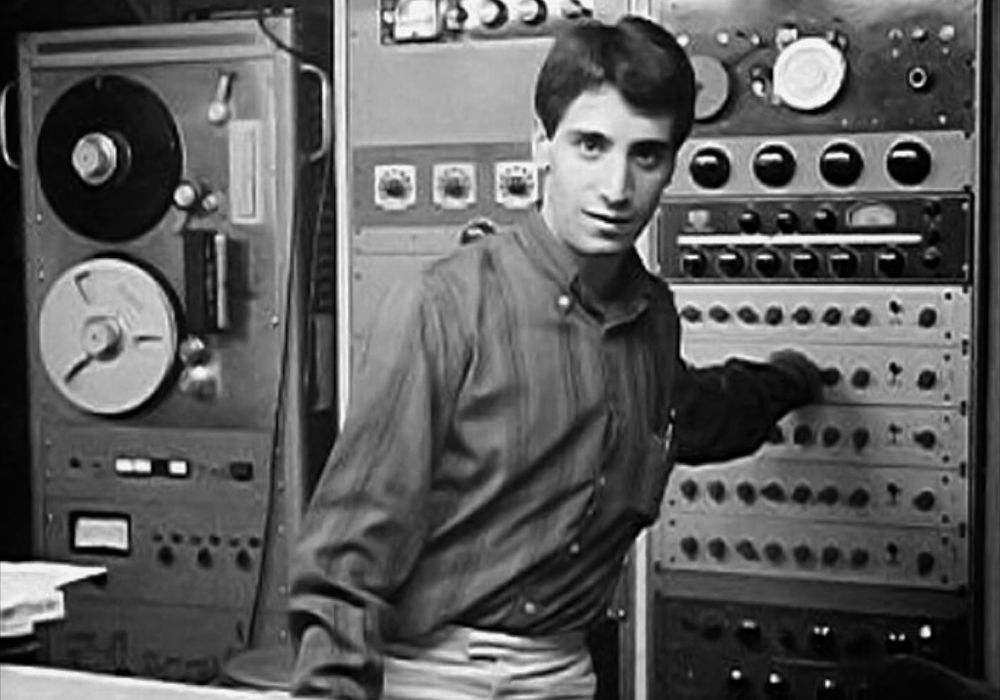

I decided in sixth grade that I wanted to be a radio or recording engineer because I was on a little radio drama we did in our grade school. They had a radio drama program they did in junior high and high school, so I took that. In high school, as soon as I could drive, I started hanging out Saturdays at United Sound, which was the biggest independent studio in Detroit. It was open on Saturday, and it was the only one that was open on Saturday. Then I decided I wanted to try and get a summer job in a studio — I'd been hanging out at United for a couple years, going out and helping one of the engineers there do his own personal remotes. This was a guy named Danny Dallas, who had actually been the engineer for the Lone Ranger! I'd been going around helping on remotes with him and had gotten my first taste of gospel music, which completely blew me away. So I decided I'd like a summer job and literally, as a joke, Danny said, "Well why don't you go down to Motown." I'd practically not even heard of Motown. I was a big classical music fan and I liked big band stuff and orchestral-acoustic kinds of things.

This is '64?

Yeah. So, I walked in the door and was taken to Smokey Robinson's office and they sat me down at his desk handed me an employment application and an IQ test! I filled in these things and then they sent me down in the basement to go talk to the chief engineer, Mike McLean. Mike gave me a tour of the place, which included seeing the first actually working sel-sync 8-track, which of course completely put my jaw on the floor. And I saw their Neumann half-speed cutting system which was just incredible. Mike was also a big classical music fan and a hi-fi nut and I wound up not getting a job at that time but becoming friends with him and wound up going over to his Friday night parties. I got to know a bunch of people and continued interning around town with other people until eventually they hired me in '65 as a mastering trainee.

They didn't want mastering as we tend to think of it now, changing the whole mix with the EQ slope, compression, etc.

Berry Gordy had the experience of getting burned by trying to do that. He had learned early on the hard way that if you didn't get it right you really couldn't do anything about it. And of course, with vinyl that was a lot more the case than with compact discs. They were very, very concerned that things not be particularly modified in the transfer. They'd rather do a new mix than try and fix anything in mastering. So I started out pretty much doing really hot flat transfers, although if we heard something that seemed obvious to change, we could throw on some EQ and send an alternative version labeled with what we did.

You mastered a lot of stuff, including many hits.

I did, along with others, yup.

When you...

The rest of this article is only available with a Basic or Premium subscription, or by purchasing back issue #30. For an upcoming year's free subscription, and our current issue on PDF...

Or Learn More