With classic '60s Northwest recordings under his belt — including The Sonics, The Wailers, The Ventures, The Kingsmen, The Standells and The Rocking Kings (featuring a young Jimi Hendrix) - Kearney was recording full-time since 1958 until his recent health issues and admittance to a nursing home. Not only is he an eclectic collector of countless stories and wisdom from all his many sessions, he has also not changed out a single piece of recording equipment since the mid-'60s! Stepping into Kearney's studio was like walking into a museum, except in this museum the artifacts are not behind a glass pane but strewn across the floor in piles of original master reels of classic recordings, tangles of old leather headphones and stockpiles of vintage Neumanns, gutted tape machines, stands and more from wall to wall. Kearney initially had various studio locations from the late '60s to the early '70s, but since the '70s he has been at his studio — an addition to his Seattle home where he's also recorded more "modern" records by the likes of the Young Fresh Fellows, The Smugglers, The Minus 5, Teengenerate and The A-Bones. He even lent his full name to a record, Kearney Barton, recorded with Wheedle's Groove, a band based around a of local funk and soul from 1965 to 1975. A previous collection of his old recordings. Kearney's ramshackle studio is no more, but the University of Washington has begun to archive and catalog his tremendous collection of tapes.

You haven't upgraded virtually anything since 1965. How come you have never changed with the times?

I like the sound and everybody else liked the tube electronics and the analog gear. I could never see any real reason to go with all the new stuff. I didn't buy every new toy. When I was at Fifth and Bell in downtown Seattle, there was a studio within a block of me that was buying every new tool that came out. He ended going belly up — losing his business, losing his house and everything else. For what? He had to have every new little thing and I don't see that. I found that the equipment I have been using does the job I want to do, and I get people coming from all over the world to record here because of that. They want to get that same sound I got in the '60s with The Sonics, The Wailers, The Frantics and others. The jazz musicians love the warmth of the tube equipment too. I find that the digital equipment is very sterile and artificial sounding, so why change?

Haven't you ever felt pressure from clients to upgrade?

I've been asked, "Do you have Pro Tools?" or whatever the new popular gear-of-the- day is, and I say, "No." They say, "Oh, okay" and that's as far as it goes. They can go to a studio that does have it. I am not going to upgrade over that. I do have a CD burner and CD duplicator because that is one of the necessary things now, but that's about it. When I'm doing a session I will record on reel-to-reel analog and at the end of the session I'll make a CD for the client to take home and decide what takes they want to use. We will work from the reel-to-reel tape before we master a record. I feel I get a fuller, warmer, punchier sound with the reel for the final mix than with the CD, but that is a client's choice.

What was your first fascination with music and recording?

Nothing really. It's strange — I went to the University of Washington as a drama major because I was interested in acting. I went two quarters and was trying to support my mother and myself. I had the thought, "How am I going to support myself through drama?" Lots of luck! I went to work full-time and took a job at a radio station, KTW 1250 AM, as a disc jockey. That took care of the ego thing on the acting. I did some recording with the station for performance groups — choirs and orchestras for broadcast. I wasn't interested in recording per se — I wasn't a guy who went out and recorded things just for the fun of it. It was just a job.

What kind of recording equipment and techniques did you use when you first started at the station in the '50s?

I used one or two microphones and a portable tape recorder — a little Ampex 601 suitcase that is like carrying a piece of luggage. The chief engineer had built a small mixing board in case we needed more than one input — otherwise we went directly into the Ampex. For mics, we used the RCA 44BX ribbon and a Shure 55. We had three of those. I also used an Altec [633A] "salt shaker" mic but we mostly used the Shure and RCA. When I was recording a choir and orchestra I used two mics and it came off great. That led me along the way of simplicity rather than to use 77 million microphones for a very simple thing. I like to always keep it as simple as possible and get the sound the way it is, and not run risk of phase problems and too much excess noise from other mics. I worked at the radio station for about two and a half years, and at the same time I was working full-time at a spice factory — grinding cayenne pepper. That was a full work week and on top of that I would work all day Sunday at the radio station and sometimes all night Sunday and also holidays. Soon enough I began to record bands like The Frantics, The Fleetwoods, The Ventures, jazz groups and whatever else at the radio station studio. I was teaching myself.

Was there a senior engineer above you?

No, I was the whole thing. I got the guy who had worked there before to teach me how to run the disc cutter. Other than that it was all by the seat of my pants. I just tried the equipment that was around to see what worked and didn't.

At this point, was a good portion of your work through connections with the Dolton Record label?

Yeah, they kept bringing in their artists. I still did a lot of commercials for ad agencies though. I would be cutting these 16-inch discs to ship. Bob Nichols did big time radio in Seattle for years — he had a little syndicated five-minute show that ran in various parts of the country. We would record those, dub tapes and send them out to the different stations. It was a combination of a little bit of everything — orchestras, choirs, local jazz groups and all the small bands that wanted to make it with the Dolton label or whoever. The bands would come in and do demos.

What kind of studio competition was there in Seattle at that time?

Bob Reisdorf and Bonnie Guitar (Dolton Records label founders) liked what they were getting with me. Previous to that they were recording at Joe Boles Custom Recorders — Joe Boles [had] a small room in his home. He didn't have any speakers to monitor so you had to use earphones, which was a little difficult when trying to get a good sound. He was over in West Seattle. Then there was Commercial Productions — in the Sixth Avenue building downtown — who stuck around for a while, but they were mostly doing radio spots and only some records. Dolton Records never tried that place out but some of the bands did. I think The Frantics had tried recording there before but weren't totally pleased.

At a certain point didn't Dolton merge with Liberty Records and move out of Seattle?

Dolton had Liberty as their national distributor and [later] Liberty bought them out and Reisdorf moved to L.A. He wanted me to go down with him as an engineer for Liberty and I wasn't really that eager to go to Hollywood. I'm glad now that I didn't.

What was the studio you were setting up?

It was Audio Recording, my own studio that I still run today — though now it's at a different location. In the fall of '61 KNBX radio had lost the broadcast that they had bought the studio for and they didn't want to be in the recording business. They gave me two-week notice they were closing it down, so suddenly I was in business for myself. Glenn White Sr. had some equipment that he leased to me and we set up the studio as Audio Recording at Second and Denny Way — I have been doing that ever since.

It seems the garage rock boom in the mid-'60s originated from Tacoma and much of it ended up with you. How did they find out about your studio and what were your thoughts on rock and roll music?

I didn't mind — it was another thing to record! The Wailers kind of knew me when I was recording all of the Dalton things — so they were aware of what I did. When they [The Wailers] formed Etiquette Records they brought in The Sonics and other bands on the Etiquette roster. There were some pretty good bands they had. I was doing country bands too.

What do you remember about recording The Sonics? You weren't afraid to push the equipment to its limits for a unique sound, were you?

My approach was to let them all play as loud as they wanted as long as it wasn't overdriving the equipment too bad. I'd back them off their amps enough where I had good control and separation but not to the point that it was quiet enough to carry on a conversation — that wouldn't be possible with them! The Sonics were kind of a funny band. They had "The Witch" out — it was a hit — and they also had "Keep A-Knockin" on the B-side of the record; which was someone else's song [Little Richard]. They only got publishing royalties for one side, so they wanted to do a session as just a throwaway to have on the B-side. They came in on Sunday and ended up doing their now classic "Psycho." I always figured that Gerry Roslie [The Sonics lead vocalist] was going to have to get a blood transfusion afterwards for his throat being turned to hamburger after the way he was doing his screaming! Everything was really hard and driving. We did the thing in about 35, 40 minutes tops — including setup and everything. As I said, it was going to be a throwaway and the whole point was to just do it and not worry about it. But there it was, man! It happened! A lot of times I find that the first takes are the best because they aren't thinking, "I made a mistake here" and then they make three other mistakes trying to make up for the first one. After a while you have no feeling left.

Let's talk about your studio for a bit. The Langevin mixing board was custom built in 1965?

That's right, and I've got proof of it over here on the master output section. The engraving around it has a little "jog" in it. Because while they were engraving we had an earthquake of 6.5 on the Richter scale, so I've got that little "ERRRNT!" right on the board. The Langevin equipment is just amazing — it is so beautiful. I haven't done anything to it since then. I added more outputs when it went up to 8-track and so forth, but it's essentially the same as it was in the facility on Fifth Avenue.

Was your mixing board and old studio's echo chambers something you worked on with Glenn D. White, Jr.? [Tape Op #39]

Yeah, Glenn helped do the layout on the board and Ken Heidt, who was working at the Seattle Center, did the actual wiring of the board. Glenn designed the chambers and I tuned them to my ear rather than his ear. He had them a little too bright and I had to smooth them out a little. I added little bits of things for absorption in there to make it so.

Before the echo chamber what did you use for reverb?

Just tape echo. At Northwest Recorders on Union Street they had a couple of Presto tape recorders that had the perfect head gap between the record head and playback head, so you'd get this great slap and tape echo with them. It was a Presto mono full-track and they had a couple of them, so I would run one at 15 inches-per-second and another at 7 1/2. I would combine them to make a nice smooth echo. I didn't have as much of the "beep... beep... beep" staccato sound. The combination of the two really, really did a good job. When KNBX closed down they kept those machines, so I didn't have those anymore. I just had the Ampex 351- 2s. I'd use one of them for tape echo and the other record on. And that's what I've still got today.

Is it true that you had a 3-track at one point?

Yeah, we went to 3-track with an Ampex MR70. It was available in 4-track, 3-track, 2-track, and I think they even came up with an 8-track later. At the time it was a new supermodel and it had a lot of extra stuff, but it had more trouble with stuff falling apart in the end, because of all of the extra little things. The relays would blow the fuses on it. We later converted to 4- track. Eventually I got a Scully 280 8-track, but we did a lot of the early things with the 3-track Ampex, which was the first step up from 2-track. If you get some of the recordings — like an Andy Williams LP in stereo — they did the orchestra on two tracks and overdubbed the vocal on the center track.

When did you add your Scully 8-track to the studio?

I think about the mid-'70s. It seems like it was just a few years ago, but how the time goes by. I try to remember what year I did exactly what groups and it all blends together.

In the late '60s, as more tracks became more common, would you get pressure from clients to have more than three?

The Beatles were doing it all on 4-track. I had one guy with a rock group say, "If you get an 8-track I'll do a lot more recording." Eventually I got an 8-track, and charged a little more because of it, and then he wouldn't record with me because I was charging more. I didn't get it because of him, but that's one of the reasons that I don't pay any attention to these guys that say, "Well, if you get such-and-such I'll record with you." I find most of those guys don't know what they're doing anyway. I'd upgrade things only as it pleased me and if it made the recordings better. When I got over to Northwest Recorders on Union Street I started adding Neumann microphones. I got a Neumann U47 and an M49 from Glenn White, Jr. and also purchased a couple of Altec M11 condensers from Glenn, Sr. Later I bought a couple of U67s from Glenn White, Jr., because he wanted to go with some other mic that he said the specifications were much better on. I don't believe in reading what the specifications are and then going with that blindly. I go with what I hear. For example, with Glenn White, Jr. we were at the Fifth Avenue studio and he was saying that omni-directional mics are louder and that you get more presence. I said, "No, No. You get more presence in the cardioid position." He quoted this formula that said that the omni was such-and-such. I had a U47 set up — it's switchable from omni to cardioid. While he was talking I'd switch it back and forth between the patterns. We set the meter and the meter was hitting right at zero on omni and when we switched it to cardioid and it went up to plus two and a half or plus three! It sounded like he took two steps closer as well. I said, "That's what I hear. I don't care what the formula says." I've always used cardioid pattern and it's paid off in a lot of ways.

Did you work with other producers often?

Larry Levine [Tape Op #45] of Gold Star Studios was up here working with Don and the Goodtimes. I wanted him to produce one of their records, so he [came] up and I was doing the engineering. I saw some studios in Los Angles with him in '65 to look at their setups. I was setting up my studio on Fifth Avenue in Seattle andwas looking for ideas. I wasn't that thrilled with the general atmosphere of L.A. I went to United Western [Recorders] and saw their room but didn't see what kind of mic'ing they were using. I was looking more for the [live] room and control room layouts.

The room sound was an important thing to you.

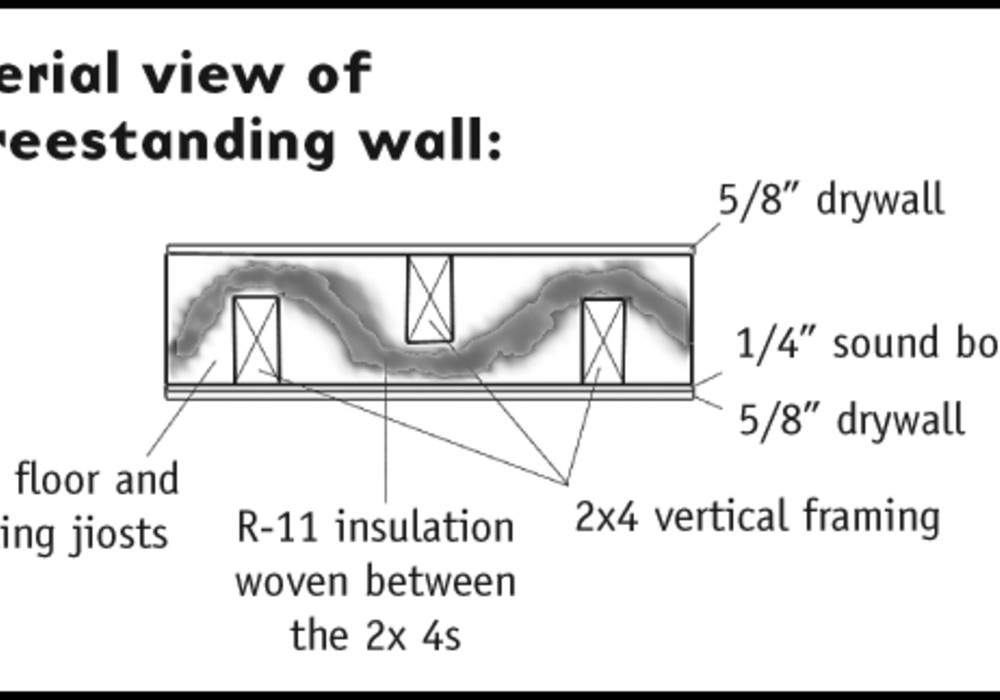

United Western had a raised area with a mixer that looked down on the band. I was that way on Fifth and Bell in Seattle. I had a pretty large space. The studio was 40 by 45 feet with an 18-foot ceiling. The control room had about an 18-foot ceiling and 12 by 30 area. I put the console and all the tape machines up there. We did a bunch of remodeling. Originally it had been a Midas muffler shop, so it was just a big warehouse. The echo chambers we had built had angled walls anyway, so that broke up one pattern. I angled another wall to give a little separation in the studio to my right, which we used for announcers and voice-over. The other walls were parallel but we had curved baffles to absorb low end, which also broke it up. We later angled the other wall. I put in a false ceiling to cut out outside noise. The ceiling was a drop-down from wire suspension, latticework and acoustic tile to give isolation from outside. I didn't hear the monorail at all. That was one of the things I checked before, to make sure there wasn't going to be vibrations from it into the studio.

Why did you have three echo chambers?

Each was a little different in size. They were pretty consistent in sound. I was going 3- track when I used them, so I could use separate reverb on each of the channels. I'd have it on the vocals, left and right on the band. I had a little more flexibility. The chambers were 18 feet tall and the dimension of one of them was 7 by 11 feet, another 9 by 13 feet. I had all angled walls in there. The plaster finish was like glass. We put a big Altec 604E speaker in there to drive the sound as well as an Electro-Voice 655 omni microphone suspended from the ceiling to pick up the reverberated sound. If the mic was too close to the speakers, it would pick up too much direct sound.

Nothing quite compares to the sound of a real echo chamber, does it?

No, it's got its own thing. I can tell the difference in seconds between a chamber and anything else — as well as a tube mic or a solid-state mic. Speaking of, I lucked out when Neumann first came out with the first U67s. There were people saying, "Oh, the U67s. It's transistor! It's state of the art!" People were selling their tube mics to buy the U67s and I was buying their old tube ones! I bought all I could get my hands on at the time. I bought them for $225 each. Shortly thereafter the price skyrocketed because they found out the transistor ones didn't sound as good. "Oh, I'm not getting the sound," they soon discovered. They came back to me trying to get the tube mics back.

Did you ever do many out of town acts that were on tour?

I did some things with Quincy Jones, Ray Brown and a young Jimi Hendrix at one point too. When I was down on Fifth Avenue a guy came in and said, "Remember me? You did a session for me in '61." I said, "Oh yeah?" He said, ?"Do you remember who was in the band?" I said, "Nope." He said, "Do you remember who the bass player was?" I said, "No." Well, it was Luther Rabb. I said I [recorded] him with the group Emergency Exit. He said, "Do you remember who the guitar player was?" I said, "No." He said, "It was Jimi Hendrix, while he was still in high school at Garfield!" I don't know if it was The Rocking Kings or what the name of the group was!

Kearney's Mic'ing Favorites

Vocals: Neumann U47 (tilted back vertically) Drum Overhead: Sony C-37A

Kick Drum: Electro-Voice 666 (tilted horizontally) Bass: Direct or Electro-Voice 666

Guitar: Neumann U67 (tilted back vertically) Percussion: Neumann U47

The Young Fresh Fellows and I felt so privileged to have worked with Kearney Barton at Audio Recording. The studio, and his house, was a bewildering jungle of tape boxes, cats and gear piled everywhere. Yet Kearney knew what he was doing. We asked if he could make us sound like The Sonics, and he did. Quickly. But when I recorded a solo grand piano track he was equally adept at capturing that. We brought The A- Bones, The Smugglers, Japan's Teengenerate, and NRBQ's Terry Adams to AR for sessions that were always the complete Kearney experience. He was funny as hell. It was like no other studio. We recorded straight to 1/2- inch tape there on an old Ampex, and never really knew what it would sound like until we took the tapes and listened elsewhere. That could have been considered frustrating, but we had faith in the man, his ear and his gear, so it became an accepted part of the beauty of recording there. It was like being transported back in time to a more innocent, authentic time. A time when so much of our favorite music was recorded.

I'm thoroughly pissed at myself that I haven't been back to work with Kearney in so long. Yet I consider myself lucky to have been amongst those who were able to truly experience the man and his realm. Long live Northwest Rock! Long live Kearney Barton!

-Scott McCaughey (YFF, Minus 5, R.E.M.)

Kearney is truly the first punk rock recordist. In Geoff Emerick's book [Here, There and Everywhere...], I think he says something about Sgt. Pepper's... and that The Beatles insisted on having his name on the back cover and that crediting an engineer was something that "wasn't done." But wait — Here Are The Sonics certainly has Kearney's name right there on the back... BANG!

-Kurt Bloch (Fastbacks, Thee Sgt. Major III, YFF)

I remember the board being completely covered with tape boxes, magazines and assorted crap while we were recording! And those monitors that pointed almost directly down at the board. So awesome!

-Jim Sangster (YFF)

Kearney Barton Playlist on Spotify

For more Northwest recording history visit our online interview with Bob Holden, of Don and the Goodtimes and studios Sea-West and HH&R. www.tapeop.com