Name an engineer/producer that has Diana Ross, Sisters of Mercy, Devo, Bruce Springsteen, Janis Ian, David Bowie, Bon Jovi, and Steely Dan in their credits. Chances are you didn't think of Larry Alexander. A veteran of The Power Station studio's glory years in the '80s, Larry has seen it all when it comes to making records. Having met through our mutual friend, Steve Masucci, it was only after looking at Larry's credits online that I realized the extent of his studio work, so I had to sit down with him in NYC and learn more about his amazing career.

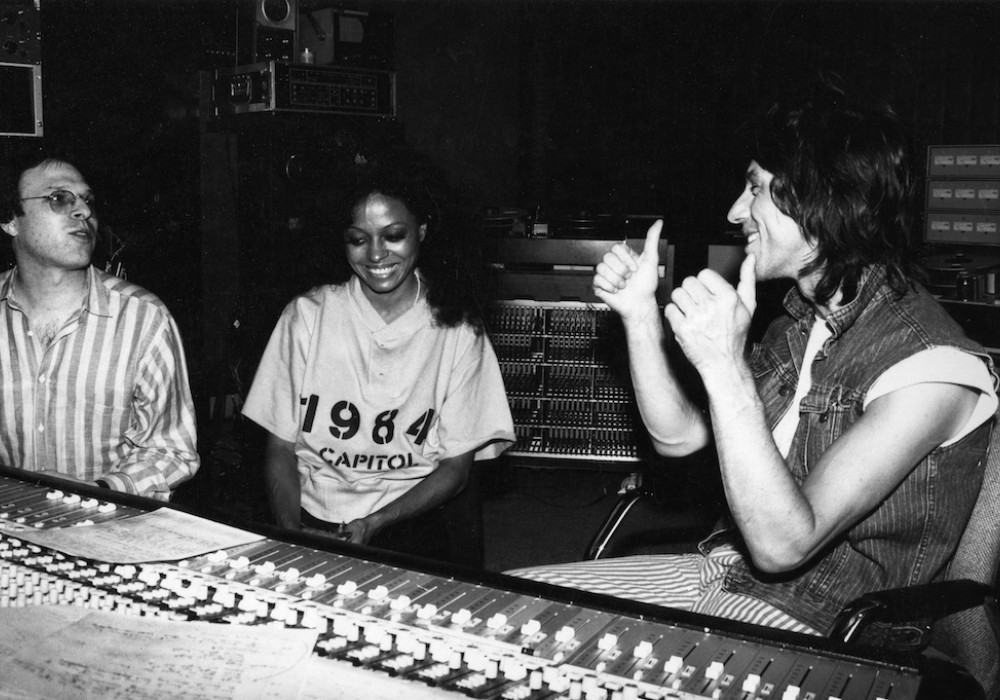

You've worked a lot with Diana Ross.

Yes. I did five albums with her. Diana Ross was one of those sessions I got from working at The Power Station. She had a two-album deal with Nile [Rodgers] and Bernard [Edwards]. They did one album and had some hits. Afterwards she said, "Let's start the next album." They said, "We're a little busy right now." And she said, "I'm not waiting." So she booked studio time to start the album. She said, "I want that same engineer, Bill Scheniman." The studio said, "Well, Bill's busy. He's working with Nile and Bernard. We've got Larry." That's how I was assigned Diana Ross. We went into the studio and had so much fun. She had the best band and the best arrangers.

Was there a producer involved who was picking the members of the band?

She was the producer, but she did hire a musician contractor. Diana said, "Get me the best band in New York!" She had people picking songs for her. She had people doing arrangements. She assembled a really great crew, which is what producers do. We get along really well. I love Diana. She's very creative, has a lot of ideas, and she doesn't like to be told no. For one of the albums we were working on, she hired a producer who came in the first day, and she said, "I have an idea I wanna try." And the producer said, "Nah. That's not gonna work." Well, day two, he wasn't on the project anymore. She's the boss and it's her money. She wants to try her ideas. If they don't work, she's the first one to say so.

"No" is a dangerous, loaded word in the studio.

Yeah. People like to be in their comfort zone. If you put somebody out of their comfort zone, they're gonna say, "No. It's impossible." I worked on that first album. We had a great time. We pretty much produced it together. The band knew what to do, and I knew what to do. As far as recording vocals: we really get along well. As a matter of fact, she likes me to record her vocals whenever possible.

You come in just for her vocal tracking?

Yes. It might have been '08 when she was doing an album, and she had a couple of producers with her. When it came time for vocals she said, "Call Larry. Larry's gotta record my vocals."

What kind of process does that involve? Are you comping....?

Well, we go in and record a bunch of takes. She's a great singer, but she doesn't like to spend a lot of time in the studio doing vocals. She'll record four to six takes, and then she's like, "Love ya, see ya. Bye! Put it together!" So then I have to comp together the vocals.

How many years have you worked with her?

I think the first album [Why Do Fools Fall in Love] was '81? There have been years when we didn't see each other, but we like working together. Also, when she was living in Greenwich, she loved working at Carriage House Studios.

How long did you work with producer Jim Steinman?

Oh, a number of years. He's such a character. He would only work in the middle of the night. He would book a session starting at 8 p.m. He wouldn't show up until like 11 p.m., and then we'd work 'til 9 or 10 in the morning. We would just keep working until the next session. The Power Station was going 24-hours a day. The next session would be ready to start and they'd be pounding on the door. Jim would be like, "Lock the door!"

At the time you were a staff engineer, but it was often requested that you work with Jim?

Yeah. I can't exactly remember how I got started with Jim, but for a couple of years I was working all night and sleeping all day!

What does that do for one's health and social life?

Well, there's no social life. The studio was the social life. After a while your body gets used to it. I was living in a house that had an attic. I put blackout curtains on, threw a mattress up there, and I would go hide. People would be mowing their lawns and I could hear kids playing. It's really hard to sleep.

Did you have a relationship at that time?

I was either married or dating my wife. She used to ask me what time I was gonna be home. Not just for Jim Steinman, but all recording sessions. I said, "Let me just say this once. Whatever I say... don't believe me. I cannot tell you what time I'm gonna be home."

What kind of projects were you and Jim working on?

Well, I think the first thing I did was mixing Bonnie Tyler, and then we did a girl group named Pandora's Box. Some of his future hits with Céline Dion were done by Pandora's Box first. Actually, one of the songs we did with Pandora's Box was "It's All Coming Back to Me Now." He had Roy Bittan [E Street Band] playing the piano, and they actually used that same piano track in the Céline Dion version. But it took us a month to record the piano.

How does it take a month to record a piano track?

We did the piano first. It was all about the piano, so Jim had Roy Bittan come in and do a bunch of takes. Roy finally said, "I'm done! I'm out of here! I've played it ten times. Goodbye!" After Roy left, Jim listened to it and decided that every version was too fast. We started going through the takes and grabbing the slowest parts. It was rubato — there's no tempo. This was on 2-inch tape, so we were editing this 2-inch tape together, over and over. First we tested it on 1/4-inch. We would do a mix and then we'd put all the takes together. We just kept refining it and refining it. I had to design special track sheets, because Jim used more reels of tape than anybody else. We were recording to 48 tracks at the time, and Jim would use a slave reel for every instrument that we would overdub. Like, "Oh, we're gonna do lead guitar? Stripe another reel [with SMPTE time code]. We're gonna do lead vocal? Stripe another reel." We would have, like, ten 2-inch reels, per song. That's nearly 240 tracks. I designed sheets that consisted of a huge piece of paper for all the tracks, and then we would start mixing them down to 48.

Was it a digital 48-track machine?

No, this was analogue. There was even one song that we mixed from three 24-track machines. The master would start, and then we would use Adams-Smith time code synchronizers. One thing I do not miss about the analog days is slave reels and time code. It was never perfectly in sync. I mean, it would get pretty darn close, but it was always skewing. It would go a little forwards and then a little back.

What do you feel you bring to a session?

I really love music. I think it's partly making people feel comfortable. I never say, "No, we can't do that." I'm willing to just go with the project. I give people what they need. There's also gotta be a little talent in there, somewhere. I've been around music my whole life. I've been doing this for approximately 40 years, and I would say more than 90% of my projects have been really great. I just love the music.