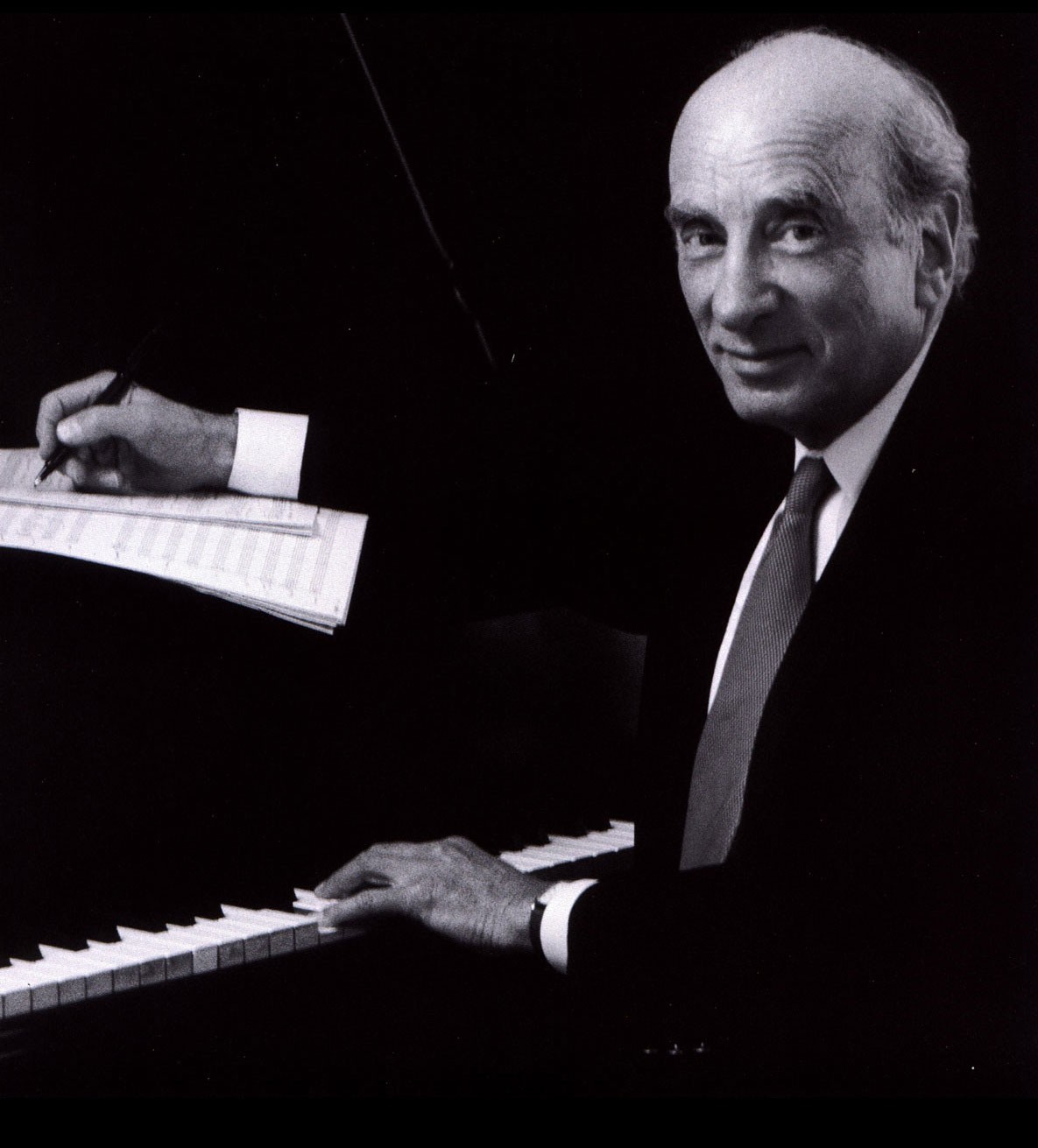

Dick Hyman has had an amazing career in music at the keyboard. With 60-plus years of experience, he's seen the industry go through many twists and turns. He's played with greats such as Benny Goodman and scored films for Woody Allen. He's also worked as an arranger, musical director and composer for countless albums, TV shows and concerts, and, if that all weren't enough, he was a pioneering performer on the Moog synthesizer in the late 1960s.

Are you still having fun?

I'm still having fun. I'm still out there. I'm still performing concerts, solo and occasionally jazz festivals and last week I spent a week in Oregon playing in a fair called the Siletz Bay Chamber Music Festival. We performed several of my pieces for orchestra and another for piano and string quartet, a piano quintet, as well as various solo things.

If you have the same group of musicians, the same song, the same direction of the style, would there be a different way to approach it arrangement-wise to make a recording vs. for a concert performance?

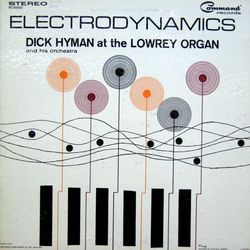

Well, the recording would be more carefully done. The recordings would be something you could plan better and you could fix the recording until you got it exactly right. The concert performance is another matter. It can benefit by being more spontaneous and sometimes jazz concerts are better than studio jazz performances for that reason. But something with the organization that most of these [Command] records had is better done and more carefully done in the studio. And you count on the sound being better. And you take that into account as you arrange. You think that, well, let's have a bass sax here and a piccolo alternating with it. Well, that's fine on a record. You can make sure everything will work great and you will have a wonderful stereo effect but in a live performance the microphones wouldn't be placed so carefully, the engineer wouldn't be so engaged and the balance would by no means be anywhere as good.

[ editorial-ad ]

So essentially the level of detail isn't going to be as great with the live performances when it comes to the arrangements.

No, the live performance may benefit from something intangible which comes with performance before an audience, and I don't downplay that. But to get things as carefully thought out and executed as what Enoch did, you really have to have a very careful engineer and a sensitive producer as well as an arranger who has thought things out very carefully in the preceding couple of weeks. And the right performers, of course.

Right. It's reminding me, I read somewhere about Frank Sinatra having a small audience in the studio when he recorded to inspire him.

Well, psychologically there's a reason to want to do that, and I can see why he would do that, and I have benefitted from that occasionally myself. But that's just a psychological matter.

You mention the jumping from session to session and that made me think about a note in your Age of Swing release where you talk about in the studio how it was typical for people to be in a jacket, dress shirt and tie.

That's right.

And maybe the jacket came off and the sleeves were rolled up.

Right. In the '50s, a gentleman would show up to work in a jacket and tie. And later on, suddenly the countercultural '60s penetrated the recording studios and people were coming to work in Hawaiian shirts, which they thought were hip. They weren't, really. And it got more and more informal at that point.

Do you think that either of those extremes is beneficial...

Well, I don't know about that, but the formality was a residue of practices in the broadcasting studios. If you were doing a radio program, let alone a television program with an audience, you did dress for that occasion. And a lot of that practice in recording studios came from that. Soon after the recording studios themselves set the pace. It's probably a lot easier to go in and be informal and not wear a suit and a tie. Everybody preferred that.

Yeah, and it would seem like particularly for percussionists and drummers not being encumbered by your clothes...

Yeah. Well, I agree. I think that is true.

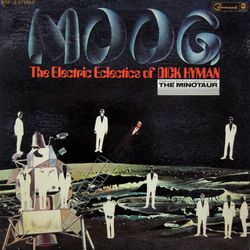

I was listening to the CD of The Electric Eclectics... this morning, and I have a couple of copies of the vinyl as well, and there are subtle differences. But I tend not to get too worried about it. I'm just excited to hear the music myself.

Yeah. I can never honestly answer the question of whether CDs sound less good than LPs did. Some people think so but I'm not sure. But at any rate, I do expect that at some time in the future, perhaps in the near future, some person will come up with a notion that it's a good idea to associate like sort of recordings with each other and then we'll have albums again.

Yes. It's a small market. But there's a lot of independent rock and certainly dance music that is still pressing vinyl.

Yeah, and once in a while I record for the Reference label, which still puts out vinyl copies of things.

So it's just interesting how you've got kind of the jazz world going, and I read about you being turned on to some Charles Ives stuff quite early, and then you've got this sort of crossover pop thing that happens and then the electronic synthesizer stuff. But it seems generally that the jazz world has been more your focus, more your interest...

Well, the jazz world outlasted the other things to my great surprise. The jazz world continues and electronic music as such and the studio scene completely are gone. So that kind of took me by surprise. Jazz has lasted and that's what I continue to do.

So exploring the electronic music world wasn't so much a choice, it was kind of what the trends were for you work wise?

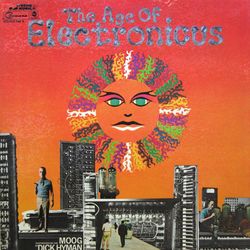

It was presented to me by Enoch and his assistant at the time, Bobby Burns, a former bandleader. All the companies were very competitive, you know, and kept tabs on each other. And this followed shortly after the great unexpected popularity of Switched on Bach and the one that Victor quickly put out by the Japanese fellow named Tomita. And Command had a rough idea that they wanted to do something like it. They left it up to me to figure out what to do but that's what we did. So all of the things on that first album were originals. And that's another reason why we did songs by other people on the second album.

For appeal, or marketing purposes, or..

Well, because we had already gotten twelve originals, we figured we ought to try the other side of the market and do tunes that were in the air.

Yeah, I like the second record but I think I prefer the first one because of its experimentation. I would have been intrigued to see where else you would have gone if you'd done another record of experimentation in the studio.

Yeah. Well, perhaps along the lines of Kolumbo in album number two. That had some very odd effects in it. I can hardly remember how we got them.

The liner notes say you used a Maestro Rhythm Master fed through an Echoplex.

Yeah. The Echoplex distorted it and recombined it and echoed it of course. And sometimes the Echoplex, which I'd used in some other situations too, made its own rhythm with which you could play along with. It made a totally new rhythm because of its echoing.

You've done a lot of film stuff too. Did you ever use synth sounds in film scores?

Well, I can't recall that we ever actually used intentionally any electronic sort of things in the film work. I remember one session where it turned out the microphone was dead on the French horn section so I overdubbed with a synthesizer what the horns had done. That sort of repair I did but I can't remember deliberately trying anything that was electronic for any of Woody Allen's films or the others.

Do you enjoy that work? What's your favorite thing to do?

I haven't done any films in a few years. I haven't been working for Woody or any other film person. It's very demanding in taking up all of your time for a little while. I enjoyed it very much. What do I like best? Well, these days I'm back to my original thing, which is playing the piano, as best as I can. That's somewhat of a turnaround, and I'm back to the beginnings. And composing. Trying to make more permanent written documents of whatever it is that allows me to improvise.

Since you've had such a history of learning and mastering other styles of music, do you feel that that has ever gotten in the way of you learning who you are as a musician? Or does it only feed it?

Well, some people — with some justification — toward the beginning thought that I was totally a copycat and a chameleon and I can understand that. But more and more in the succeeding 40 years I've come into my own way of playing, which is based on certain jazz characteristics, certain things I've learned and I'm still learning, I hope, from Bach, Chopin, Shostakovich, Stravinsky and so forth. Whatever I play now is a result of everything.

Is there any of those characters that you could imagine if they had been around later...

Oh yes. As I always say this: Chopin in many essentials was a jazz pianist. And he left different versions of some of his pieces in different publications. He altered certain cadenzas or passages precisely like a jazz guy would do. And then, even without comparing different publications, in one nocturne you can see how certain of his decorations and cadenzas are rather more arbitrary than they might be in Beethoven, say.

And by arbitrary you mean that there are slight variations on the previous version?

Well, sometimes it's the practice of jazz performance to play a little bit of the melody and then to put in a little bit of a decoration. Decorations can be one or the other. They don't have to be the same decoration. From performance to performance they may change in the hands of a performer who likes to do that kind of thing. That's what Chopin did, excellently.

Could you imagine any of those guys messing around with a synthesizer or being in a modern recording situation? What do you think Bach would do?

[laughs] I don't think Bach needed to do anything else than what he did. Which is one of the high achievements of the human race.

It's true. I have a vision of him just doing it all himself and overdubbing 'til the cows come home kind of a thing. Certainly these folks worked their music out and they had very top down view of these grand pieces but with modern recording technology a lot newer music gets built up layer by layer and isn't something that is necessarily thought of completely at first?

It's true. So maybe someone could say that Bach would have done that. That's supposition..

Oh, sure. No one's gonna call us on it!

Yeah.

Is there anything else that you'd like to add or that you're interested in sharing in regards to recording or studio experiences?

A friend of mine who's not a musician liked to come to recording sessions. He told me he was absolutely moved by the first reading of a new arrangement by a pickup orchestra of expert players. And there is something magical about that. All players who have no problem reading or executing anything that appeared on their parts. It's a great experience for the arranger, who is often the conductor, as you know, as well, to hear back what had only been in his mind. And for my friend, who hadn't heard it at all, he tried to describe it as what I think is sort of a transcendent experience, that suddenly there was something new where there had been nothing and nobody had any notion except the arranger of what was to come. This is one of the great feelings of recording among top notch players that we had in those days.

Something from nothing is especially fascinating and thrilling, particularly with improvised music, too.

One of the remarkable things of recordings, back into the twenties, is the fact that these very formal orchestras, like Paul Whiteman, left space for improvised solos by certain known soloists. And that the soloists — if they were as remarkable as Bix Beiderbecke — would produce a different solo for successive takes of the same piece. We have several different recordings of the same piece in rehearsal or issued for some reason in one market or another in which Beiderbecke plays a different solo entirely. The fact that you have this peculiar meeting of formality and improvisation, I think is a very American idea. Taking into account an individual's unexpected, unpredictable contribution to an otherwise formal arrangement that everybody plays the same. That's remarkable and I think there's something sociological about it. If you follow me. Of course, that practice has continued up through the period we're talking about. It's hard to tell now. Probably would be the meeting of the "formal" and the "informal," I guess.

Yeah. I like that. That makes sense. It was a great pleasure to get to talk to you.

If I write my book I'll have more to say.

You should! You've experienced incredible transitions in music history.

Just by being around!