I found hip-hop/dance music pioneer Jon Baker residing in Port Antonio, Jamaica — a town he decided to settle in after experiencing a blazing a career in New York and London. With a past that includes the seminal hip-hop label Gee Street Records and studio work with Stereo MCs, P.M. Dawn and Gravediggaz — he's now added running an exclusive hotel and residential recording studio, Geejam, to his résumé. Among the artists that have recorded there are Gorillaz, No Doubt, India.Arie, Dru Hill, Bebel Gilberto, Les Nubians, Wyclef Jean, Björk, Drake, Santigold, Major Lazer and Amy Winehouse. Recently Jon has been working with the legendary Jamaican mento band, The Jolly Boys, and produced their covers album, Great Expectation.

I know your music career started in New York after working in London.

I had four absolutely bonkers years in Manhattan. I was a fashion designer at the time — I used to make the clothes for Spandau Ballet, among others, in the very dandy New Romantic movement. I was vested to set up a show for Spandau Ballet, so I landed in New York — sadly on the day that John Lennon was assassinated — and stayed at the Gramercy Park Hotel. I set up the show with Jim Fouratt and Rudolf Pieper [founders of Danceteria] at The Underground Club. I was just blown out by it and I spoke to my mentor, Steve Dagger [Spandau's manager], and said, "I'm going to have to check this out a bit more." I went into the club scene and I started bringing bands over from London. I'd put them on at Danceteria and promote shows. I also started selling my clothing line in SoHo. I got immersed in New York culture — Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat — everybody was there and I was lucky enough to be part of it.

So when did you transition towards your label and being involved with studios?

I linked up with Ruza Blue [aka Kool Lady Blue], who was the founder of Club Negril and The Roxy. I was the doorman at The Roxy. Ruza introduced me to hip-hop at Disco Fever in The Bronx. From that point on I knew I wanted to do one thing — music. I left New York in '84. I was profoundly influenced by hip-hop. I saw it as very similar to the punk movement that I came out of England in '77 when I was at The Chelsea School of Art on The King's Road. When I got back to London I linked up with my former wife, Ziggi Golding — a German/Jamaican fashionista. I started Gee Street Records in an old warehouse on Gee Street. I bought a Tascam 16-track machine and a small board and we started recording hip-hop. We were one of the first hip-hop labels in London. Through my experience in New York I knew a lot of the early players coming up. Russell Simmons' Def Jam had started to pop. Adam Levy had Warlock Records and Tom Silverman [had Tommy Boy Records]. I knew all these people from The Roxy.

Where were you drawing talent in from London?

Tim Westwood was doing a hip-hop show on the radio. It was just coming out of the London dance scene. The dance scene was burgeoning with acid-house and house music — hip-hop was on the rise. I linked up with two particular people — one was a pirate radio DJ called Richie Rich from the UK who was an incredible talent. I also linked up with Rob [Birch] and Nick [Hallam] from The Stereo MCs. We started putting out "white labels" [12" records, primarily for DJs]. We made a rule — we weren't going to make demos — we'd make up a thousand white labels and then sell directly to the store. We started by literally selling records out of the back of our car.

What were some of those records?

We had a number of early successes. We did Stereo MCs' albums — 33-45-78 was an acclaimed record. We had Salsa House by Richie Rich. I had signed a white rapper called MC Goldtop — I took his single to New York and Adam Levy loved it so much I swapped the license for the first Jungle Brothers album Straight Out the Jungle. We took it back to England and did additional production on it. I organized a hip-hop tour for the Native Tongues and Queen Latifah. I then licensed Queen Latifah for certain territories in Europe and the UK. We then set up shop back in New York.

Were you still recording?

Let's clarify my role in the recording area. I was influenced greatly by Malcolm McLaren and impresarios who put things together. During my punk days I had met Malcolm when I was only 15 or 16 years old. I like putting people together, so I sort of became a record guy by way of A&R. During the '80s and '90s, when I had success with these records, I basically left my engineers and producers to do the records. I'd go in and supervise a mix. I always had a good reputation for choosing the right single and making sure we had the right radio mix, which is all- important. You've got to remember that Gee Street was an underground label, but I enjoyed crossing the records over into the Top 40!

Who were some of the engineers you were relying on in the Gee Street phase?

Toby Whalen, Tony Maserati and Michael Fossenkemper.

What were the virtues of these guys?

Everyone had their own approach. It used to be very important to me that I could set up an energy and a vibe between my artist, the producer and the engineer. There's a language of music communication that isn't always in "middle eights," "top lines" and everything else. You can be an A&R man, spending money and signing acts, but the true A&R man sees the act and takes it all the way through the marketing and promotion — none of the acts could have gotten off in America unless I could interpret it to the promotion team.

What eventually happened with Gee Street?

We were with Island Records. In 1996 Chris Blackwell left Island to start Palm Pictures and I had an opportunity to buy Gee Street back. I did and then I re-sold the majority shares to Richard Branson [Virgin Records founder] and became co-president of V2 Records. I did that from '96 to 2000. Then I decided on a complete lifestyle change, so I relocated to Jamaica in 2002, sold my loft in The Village and kind of reinvented myself from the ground up. The idea was for a brand called GeeJam, i.e., "Gee" but with "jam" for "Jamaica" instead of "street" — a lifestyle brand that would bring together music, media and all the other things that interested me. I had bought a raw piece of land down here in 1990 that had a derelict house that is now Sanwood — our three-bedroom villa. Then, in about mid-1996, I brought some equipment down here and we started doing some recording. It was just an incredible energy and focus for artists to come down here. I actually cased up my studio in London and sent it here. We had an Amek Mozart desk, a 24-track Otari tape machine we bought from Peter Gabriel's Real World Studios, and a load of vintage outboard gear. We used that from '96 to 2000 to do my in-house projects down here.

What room did you use?

We used the office.

So you set up the mics in the office room?

Yeah, we used the bathroom for the vocal booth. It was a really good room! We had our own power source [important in Jamaica -ed.]. We flight cased everything up so all you needed to do was plug everything in. We'd pre-wired the whole studio in London.

What were some of those projects?

I did Jungle Brothers and some Stereo MCs.

Who was engineering?

Toby Whelan, a brilliant British engineer.

How did he adjust to the change in scene from London?

Well, we always laughed because he was in a damp basement on Gee Street in East London and then he came to this! [gestures to the Caribbean Sea] Anyway, the industry was basically falling apart. Fortunately I got some incredible early sessions. We did the Gorillaz's debut album and a good part of No Doubt's record Rock Steady. India.Arie came down to do a lot of records here. Common came down.

All at the villa?

No, that's when we had opened the new facility in 2000.

Why did you decide you needed to build a studio?

Well, I'm a bit obsessive. It was a massive job, 'cause we had to build on the side of a freakin' limestone cliff. Doing anything in Jamaica is different to the UK, Europe or the US, because all the materials have to be flown in. Labor is very basic — you don't have the machinery here that you would use on normal building sites.

When you designed the studio, what were you envisioning?

One of the most important things of an A&R man is communication with his artist and producer — getting their attention and creating an environment where they can focus. How many times have we had debut albums that have been huge smashes with very talented artists, and then they can't deliver the second record?

The sophomore slump...

Yeah, exactly. Why? Because more often than not they are bombarded with a thing called fame, which is a huge distraction, and they have money and wealth. I've seen it all. [This place is] for taking someone down to the most unthreatening environment so they can focus and get healthy in body and soul. There is nowhere better. A lot of A&R men ring up and say, "Oh, they're not going to do anything. They're going to be on the beach."

And?

When they come back from the beach they record all night. And the board is up exactly as they left it. It's a true lockout — no one else is in there. We've had sessions where we've had people going around the clock. There are many different reasons for recording down here, but I think the most important is inspiration and focus. You're not distracted like when you're in a city studio, or even in your own home studio. I've always been a big purveyor of taking people out of their normal environments. I believe it spurs creativity. After I discovered P.M. Dawn I needed to demo them. I realized that one guy was a security guard in a hospital who was 17. They'd never set foot out of a very poor part of New Jersey. I stuck 'em on a plane, brought them to Gee Street Studios in London and we did all the demos there. We then recorded the album at Berwick Street Studios in London. They were ducks out of water. This was a complete culture shock, but it shows on the album. You hear the "pop" sensibility. It's something I still do to this day.

Most Jamaican recording is centered in Kingston. This is a totally different environment.

Yeah, I think the fact that we are in Jamaica is very relevant. I've always been influenced by Jamaican music — I'm passionate. I've taken citizenship in Jamaica — they're not going to get rid of me that easily. But what we've done here is on an international level. That's different from the recording setups that used to exist in Kingston — there are only a few studios left. There used to be hundreds of studios back in the heyday, but with the demise of the industry, and more importantly the advent of technology and recording at home, a lot of studios have gone into small production facilities in people's houses.

If you need something for the studio, what are the difficulties in obtaining it up here in Port Antonio?

We've got a very good logistics team. We can generally get anything we need within 24 to 48 hours. We like to do good pre-planning on any session. Our engineer will speak to the label or the management company and think of every possible thing they may need.

When you built GeeJam were there problems getting the gear into Jamaica?

No, the government has been very supportive of music and film. They've managed to recognize that this is a big export for Jamaica. They do a lot of duty free waivers. It's always been easy for bands and production to come out.

Was it you who designed the basic plan of the studio?

I chose the basic location. I based the size of the studio on two trees on either side because, at the time, I was not going to chop down any trees on the property. Later a hurricane came along and knocked one of the trees down.

Who designed the plan?

Tkae Mendez. He was also the engineer/designer who built Wu Tang Clan's 36 Chambers Studio in New York. I met him through RZA, with whom I did Gravediggaz and Bobby Digital albums. Tkae came in and gutted the room. He worked with our local studio supplier, Augustus "Gussie" Clarke of Anchor Studios; it was then that we decided we wanted a combination of analog and digital.

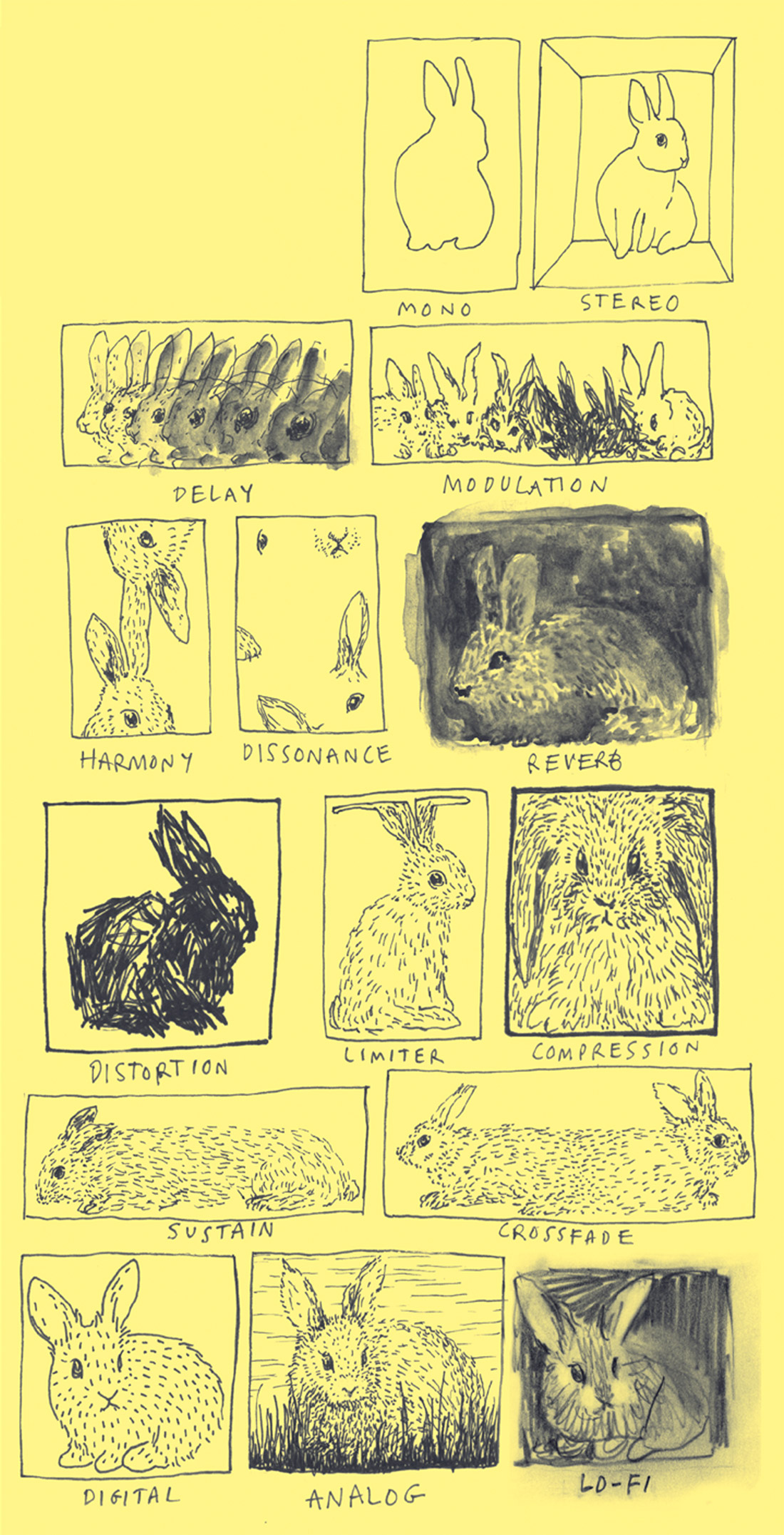

So you have some analog elements?

Yes. There are still a lot of bands and mix engineers that want the 14- or 16-foot long desk. I've always said we're not in business to compete with the big studios. We've got what they can't have. It's unique compared to the other residential studios because of the energy and vibe that Jamaica has. No one encroaches on each other's privacy, but if you want to engage and interact with the staff, the locals or the other guests, you can. One of the most important things we did was deciding to create an association with Rupert Neve Designs. Josh Thomas and all the people there have been incredible with the support they've given us. Putting in a desk of that type — their 5088 [Discrete Analogue Mixer] — has been an incredible asset to our model. We're actually in the midst of purchasing Studer 1-inch and 2-inch machines because we've decided we want a very strong analog side to the studio. We're having some custom-built Augspurger monitors designed, as well as a selection of KRKs and ADAM monitors. So we're gearing up now with [engineer] Tom Elmhirst, who comes down regularly. He mixed The Jolly Boys album at GeeJam as well — his credits are incredible. He did Amy Winehouse, Mark Ronson and Seal's recent album, just to name but a few. We're beginning to get producers and mix engineers who are loving the room, resulting in them coming down here more regularly. But what we were finding is that we needed to have a selection of their preferred monitoring.

Is any of the vintage analog stuff available from the old studios in Kingston?

After the great Clement "Coxsone" Dodd passed away, Alborosie (an artist/producer who was in-house) got down to Studio One in Kingston and bought all the old reverbs and so forth. We don't have much of it, but there are a few things around.

What about the design of the live room. Doesn't it have picture windows?

We had to go through several different approaches to have so much glass and view. We have very thick curtains that we can draw to dull out all that sound and reflection that might not be conducive to an engineer or session.

Was it your idea to have that view?

Yes, totally. I come from a visual background influenced by all those years of being involved in fashion, music and all the marketing aspects. For me it was not acceptable to merely have a great sounding room.

Do some artists find that beautiful view distracting?

They're surprised and inspired by it. But sometimes the curtains are drawn because it's all about the sound, as it should be.

Who are some of the people who have been down to record at the new studio?

In 2010 we did Santigold's upcoming album. We worked heavily on the Major Lazer album with Switch and Diplo. Another person who works with us quite a lot is Mark Howard. Last year we recorded Drake. Two of his singles were done here. Also Jay Electronica, an up and coming young rapper. We also had Amy Winehouse down here.

Did they bring in their own engineer for the Amy Winehouse project?

Yeah, Salaam Remi [Gibbs] was the producer and Gary "Mon" Noble was the engineer.

Amy had a marvelous voice.

Amy was cool. She loved the vibe. She met Albert [Minott] from The Jolly Boys who played one night at the Bushbar [at GeeJam]; he played his rendition of "Rehab," which she loved. She was very supportive when The Jolly Boys went to the UK. Last year we had six major projects, which was great. And you know what? No one did the exclusive lockout. They all integrated with the existing guests and it worked beautifully. Which was a surprise to me. You didn't have to throw guests out because musicians were coming.

You hang all your gold records in the studio's loo.

They're the past. Besides the john is the one place where someone would find time to look at them. r

www.geejamstudios.com

Peter Zaremba has been fascinated with recording since his father brought home a stereo 'Voice of Music' tape recorder in 1958. He's been recording with his band The Fleshtones since 1976 -.

the busy buddyblogspot.com

Dale "Dr. Dizzle" Virgo

Dale is a graduate of the famed Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts, School of Music in Kingston, Jamaica. He works as a house engineer and producer at GeeJam Studios.

It's good to catch you in the middle of recording The Jolly Boys.

We're rehearsing and recording, getting the vibes going.

When you did the basic tracks for the Jollys, did they play live?

I tried to mix it up. On some tracks I took the drum machine and sampled some of the live stuff like the rumba box. It's in my drum machine to give it that "real" sound. I didn't quantize it when I played it back, I just played it like I was playing the rumba box. The guitar is live. Some of the other tracks use live drums, which I go into the studio and play on the track. So, the resonance of the drums — you want to hear that in the record. Those things add life to the music.

I see you've got the rumba box mic'd up with a [Shure] SM57. Is that how you recorded it?

No, that's just for rehearsal. For recording we use the Neumann condenser mic. You don't want to just mic the box, you want to record the whole room — the way the box resonates and moves the whole thing from the floor up.

www.dizzlelab.com