We last visited legendary console designer and audio guru Rupert Neve in Tape Op #26, in 2001. In 2005 his corporation Rupert Neve Designs debuted the amazing Portico Range of equalizers, mic preamps, compressors and more. A few years later the 5088 Discrete Analogue Mixer (Tape Op #73) made its debut and I became the very satisfied owner of a 5088, serial number 27. I traveled to the serene rolling hills of Wimberley, Texas to meet up with a very gracious Rupert, Josh Thomas (Director of Sales and Strategic Alliances), and Craig "Hutch" Hutchison (Senior Design Engineer, formerly with Manley Labs).

Josh, how did you meet Rupert?

Josh: I was working for a place in Chicago called Soundlink Audio with Howard Sonyacoff and Lewis Frisch. He got me passes to the AES show. I showed up and I was basically a kid from the Midwest in the big city of New York. Lewis said he wanted me to meet somebody; I turned around and he introduced me to Rupert Neve and Les Paul — three minutes in! [laughter] It hasn't gotten better than that since!

Rupert: It would've been '93.

J: It was the US launch of the Amek Medici [equalizer]. R: I joined Amek [Systems and Controls Ltd] in April of '89. In '90 and '91, there were several visits to the US to meet different dealers and distributers for Nick Franks, who was the owner of Amek.

When did you stop working for Amek?

R: When did Amek wind up?

J: Harman [International Industries] didn't know what they were going to do with it, it seems. I think '05 is when they officially stopped trading.

Were you still under contract with them at that point, or had you moved on?

R: I was under contract. I think it was initially five years, but that just rolled on and on. Nick Franks and I had become good, personal friends. I don't remember that we had any formal renewal of the contract; we just continued as before. Nick had a number of problems on in the circuits and the sound. He wasn't an engineer or designer; but he could tell me about transformers and whatnot. I would make adjustments and then we would make comparisons between transformer-less circuits and ones that had transformers. I found that extremely helpful. You can measure and measure and you'll get results, but it's not definitive. You need to get the golden-eared person to supplement your own findings on the circuits. Billy had a lot of ideas and between us we pulled The Masterpiece into shape. Now, you came in on the scene shortly after that? used transformers. They've been very successful and they still are.

My feeling, as a recording engineer, is that you just grab the gear that works and you don't think about what's in the box. But it's also sales, preconceptions and hype.

R: It's a question of how you use them, like everything else. When it came to a console, I wanted a greater dynamic range. We just wanted something straight- down-the middle, the best there is. So, we developed his plate with the running of the company and various his plate with the running of the company and various financial problems, which had accrued from that. He had some very good people who joined him. When did John Oakley join?

J: John would've been 2001 or 2002.

R: Yes, yes. John had been with Soundcraft. He joined Amek as Managing Director. Unfortunately not long after he joined Amek he had a heart attack and was out of commission for some months. But he sailed back into the stormy seas and did a first class job. I was still generating new ideas and products.

Josh, did you work for Amek at some point?

J: I started working for Amek and also became friends with Nick Franks. When Harman exercised their right to purchase Amek, I was with them [Amek] for another two years — five or six years all together. I was there for the 9098i in-line console and the Channel In a Box [channel strip].

How did Rupert Neve designs come out of this? You also had your ARN Consultants Corporation at this time?

R: My wife [Evelyn] and I came over [to the US] in 1994. I was with Amek at the time and continued to work with them doing design work and a certain amount of representing — going to shows and meeting up with people. I was doing additional consulting and design work for various people. I met up with Taylor Guitars and did some design work for them [the acoustic K3 preamp and ES pickup].

What lead to Billy Stull's Legendary Audio and The Masterpiece Analog Mastering System in 2004?

R: I actually met Billy quite early on. He came to see me after I first arrived in Wimberley. He's a great guy. The thing that was so impressive to me was that Billy has the best pair of ears I've ever come across in many years. He could listen and tell you what was going on in the circuits and the sound. He wasn't an engineer or designer; but he could tell me about transformers and whatnot. I would make adjustments and then we would make comparisons between transformer-less circuits and ones that had transformers. I found that extremely helpful. You can measure and measure and you'll get results, but it's not definitive. You need to get the golden-eared person to supplement your own findings on the circuits. Billy had a lot of ideas and between us we pulled The Masterpiece into shape. Now, you came in on the scene shortly after that?

J: Yeah, right when he was trying to make a commercial go of it as a product. I'd just finished working with Amek. I'd helped with the Taylor guitar preamp/pickup just before this. Rupert and I'd kept in touch. We'd submitted a bunch of designs and ideas that Rupert had brainstormed to Amek. It became pretty clear that they were either uninterested or incapable of moving forward with the designs.

What became of The Masterpiece?

J: It was a tough product at the time because a lot of the mastering guys were transitioning "into the box," as it were. It has a lot of features from the master section of a console, so a lot of the mastering guys already had custom consoles from Manley and what not. But there are a number of them out there.

R: I believe production was 25 units. I don't think we actually got as far as 25, but it was not insignificant.

Hutch: I was incredibly impressed. I was building mastering consoles that had almost no features. [at Manley Labs]

R: Legendary Audio was Billy's company. I can't even remember the arrangement; it kept changing. He was trying to sell The Masterpieces and do it all himself, which was a big mistake that he made. It is the worst thing in the world for a designer to try and sell his own design. He would spend huge amounts of time on the phone telling people how wonderful The Masterpiece was. It was quite good, from a marketing standpoint, but he could never get around to closing the deal. So Josh appeared on the horizon and started to bring some order into that chaos. Billy was short of capital. Who ever has enough capital? [laughter] He was trying to buy components on a one on one basis for the next unit and was always short of this or that. He had a very good subcontractor, who we still use ourselves. They went through and somehow managed to get things working to the standards they should work. As Hutch was just saying, it wasn't the simplest of units. It needed capital for promotion and sales. It would've been a lot more successful if it'd had those things behind it. But the ones that have sold [are to] satisfied customers. We continue to get reports of what people have done with it. I suppose it's fair to say that the unit was top-quality ICs [integrated circuits], but it was not discrete. There was a huge amount of features in that — a lot of the things like sensitivity switching and EQ switching were all solid-state, which worked extremely well. We still go back and look at some of those circuits when we want to do something similar on present designs. I think the Portico range came out of discussions that Josh and I had. Again, they were sort of hybrid; though they were mostly ICs but there is quite a lot of discrete stuff. We used transformers. They've been very successful and they still are.

My feeling, as a recording engineer, is that you just grab the gear that works and you don't think about what's in the box. But it's also sales, preconceptions and hype.

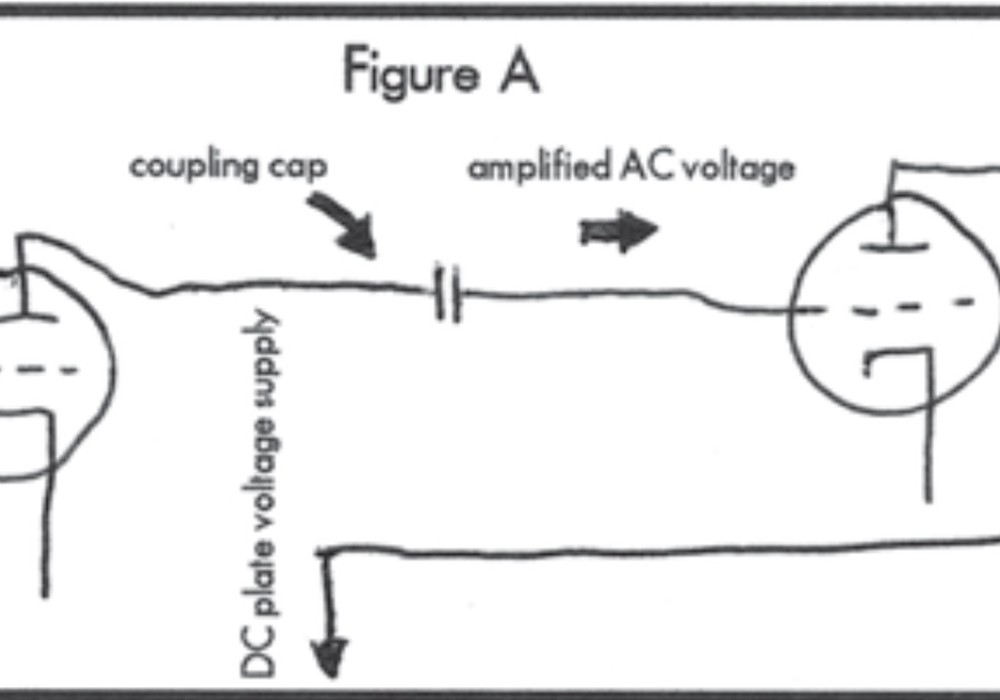

R: It's a question of how you use them, like everything else. When it came to a console, I wanted a greater dynamic range. We just wanted something straight- down-the middle, the best there is. So, we developed our own discrete op-amp. We used high-voltage rails, which you can't do with ICs. You're limited. We went up to plus and minus 45 volts. The result is the 5088. I don't think there's any other piece of equipment on which I'll blow my own trumpet! [laughter] We're still on the same track. Not everything we're doing is 90 volts — it doesn't have to be. We've established the Portico range and there's no backing down from that. The components are more readily available. Capacitors that can handle 90 volts are in limited supply. Bring it down a few volts and the prices drop quite dramatically.

Were you nervous to start a new company with Rupert Neve Designs?

R: I was always wanting, and always wanted to have, the necessary vehicle to manufacture the designs that were coming out. You've got to set up some sort of company. Josh and I have known each other for a considerable amount of time and it seemed natural that we would join forces. Originally it was just my wife and myself. Bit by bit we expanded the company. I wasn't nervous, no.

One thing that would streamline producing the Portico range is using a similar form factor.

J: We had six products out within two years. I've never seen that with any other company that I've worked with.

Hutch, when did you come on board? You had a distinguished run at Manley.

H: Just a little over four years ago.

J: Rupert went from working out of a spare room in his house to having half of this building. Rupert Neve Designs was growing at such a rate that it was obvious that we needed help. The trajectory of the business made that obvious.

People knew of you more as a tube person. Was it fun to come over here and think of some different problems to solve?

H: The whole tube thing is actually something I picked up at Manley and I carried that theme [over here]. My background before that wasn't really tubes — it was consoles and a whole range of studio equipment.

R: I first met Hutch at Electric Lady Studios. The first Focusrite console went in there. He was very much into high-grade ICs.

H: Rupert probably has more experience with tubes than I do! [laughter] But yeah, I took that pretty much as far as I could. Then this opportunity came up and I considered it an honor. I had to do it. The bulk of what I'm doing is helping the engineering team. When they stumble on something, or need a fresh approach or a starting point for a schematic — Rupert does that, I do that. It's a teamwork thing. The most important thing I do is teaching engineers how to listen.

R: We have a good team of people. But I find, in this day and age, we don't easily find the kind of designer that used to be readily available. This is no reflection on the people we have here, but an engineer used to know what a decibel was and would be able to understand basic physics. What is 3 dB? What does that mean to you in terms of sound pressure and whatnot? This is a problem we have today — very intelligent people that want to learn but haven't been taught. It's like kids reading without knowing what the alphabet looks like!

H: Back in the '80s when I was a working in studios, it seemed to me there was a lot of shaky, questionable gear going on, particularly in that decade. But there were consistently good pieces coming from smaller manufacturers: George Massenburg, Rupert... and then the list gets pretty small! [laughter] But I thought, "How are those two guys consistently producing great sounding gear?" Then it occurred to me that they were listening. They were listening to what they were building and the other guys weren't. Whatever pressure we may feel, from whatever direction, it's got to be high-quality.

Where's the company at now?

J: It's real simple — we just have to sell things. And we need happy customers, like yourself. It's not easy, but it's fun. We've got a great group of people. We're doing things now that I think 20 years from now people will look back on and say that it's been meaningful.

_disp_horizontal_bw.jpg)

_display_horizontal.jpg)