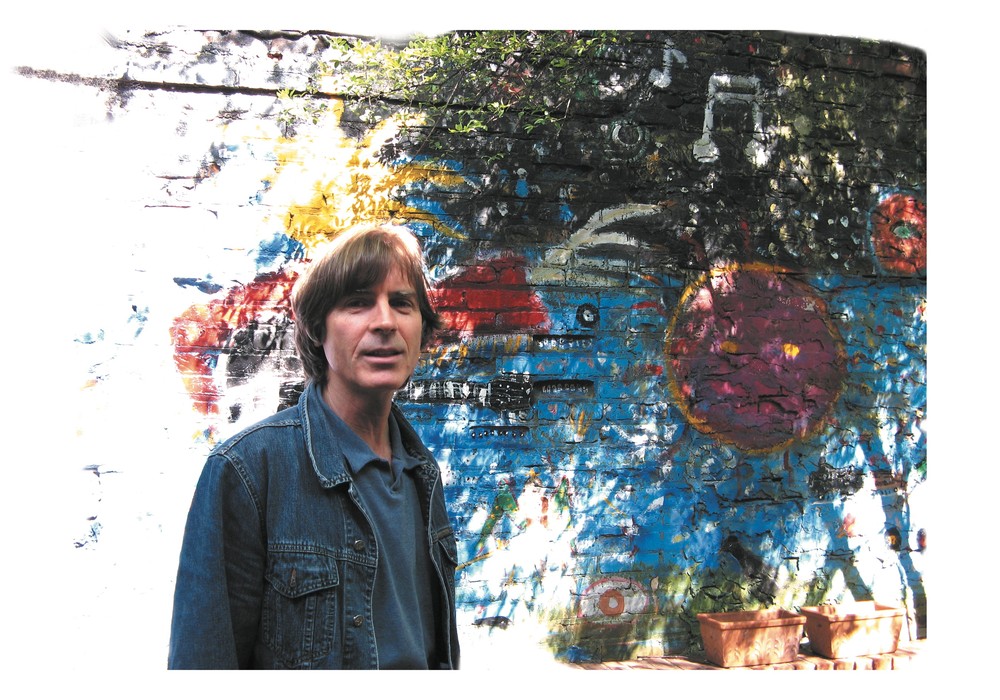

It's not an exaggeration to say that most non-Icelandic people come to know of this tiny island country through the records Valgeir Sigurðsson made with Björk, and there's no denying that these records were some of the most innovative, genre-bending albums of their time. From an engineering and production perspective, Sigurðsson work with Björk helped make her desire to blend pop, punk, electronica and neo-classical sounds and sensibilities into a sonic reality, and doing so required a fearless exploration of cutting-edge recording and production techniques. While hanging out with this softly- spoken yet candid Icelander, I came to quickly realize that Björk was really only one snapshot in a long-arcing career that, in many ways, is only now starting to hit its ful lstride with the development of his own label and creative collective, Bedroom Community.

Artists such as Ben Frost, Nico Muhly, Sam Amidon and Puzzle Muteson are collaborating with Sigurðsson with the Bedroom Community label to create albums that defy genre: Frost's music can remind one of wolves mauling prey; Muhly's is similar to the a global information network on speed; Amidon's reminds one of an Appalachian lucid-dream; and Sigurðsson evokes a wistful, longing landscape. Yet, all of these albums benefit from Sigurðsson highly articulate production style that elegantly combines acoustic recording and electronic manipulation. I met up with Sigurðsson at his Greenhouse Studio, off an impossibly entwined residential cul-de-sac about 10 minutes from downtown Reykjavik. His space is uniquely modern and open, designed to let the rain be heard and the outside air in.

Where did you grow up?

A small town directly North of here — about a three-hour drive — called Blönduós. It's on the main road so it's quite a busy place.

By 16 you had an internship in a studio?

Yes. I finished my basic schooling and then moved here to Reykjavik and began [college]. I had some songs that I had been writing, I saw an ad in a paper offering a day in the studio for a really good price, so I called them up and booked time. I went there with my drum machine and keyboards. The engineer noticed that I found my way around the studio quite quickly and was interested in what was going on. It was a little basement studio with an Akai. I don't know if you've ever seen these Akai desks, with a videocassette for tape?

Rings a bell. Eighties digital?

Right. He had a few compressors and some nice mics, too. He was losing interest in the place and asked if I'd come help him out. I soon took over his more mundane editing jobs. He did a lot of radio commercials and voiceovers. Lots of going to tape, cutting and splicing — so that was my first task. He'd leave me alone for hours with a pile of tapes and a script and say, "Hey, if you could get this done before I get back that'd be great." Then I helped him out recording some bands. He said to me one day, "I'm going to sell this place. Do you want it?" I said, "Sure." I was 17 and was spending a lot more time there than at school. I actually convinced my parents to help me sign the loans because I wasn't old enough to do it myself. It wasn't a lot of money, but for a 17- year-old it was enough. He offered to sell me the equipment as well and to take over the rent for the studio space and the apartment, which I did. That's what I did from 17 to 19 years old. I was trying to find projects and make it work. I was making the payments, learning more about studio life and making my own music. I was making a living, mostly by doing the commercial and the voiceover jobs. Sometimes bands would come in. Then I decided to sell the equipment to go and study. I needed to learn more in order to be able to go to bigger studios.

That's when you went to London?

Yeah, I went to SAE [Institute]. At that time there were no Neve or SSL [consoles] in Iceland. There were quite a few studios with okay desks, but nothing great — and none of them had jobs [for me]. Those were in private studios, and you had to create your own thing. They had a Neve desk at SAE, and still [were] all about tape machines in '89.

How long was that program?

It was a year — a postgraduate thing. I convinced them that since I had the two years of experience, I shouldn't have to do the first year. It was good to be there and to try to get a little taste of the real world. While I was in London I was trying to get jobs in studios, but it was hard while I was studying. I decided to stay around after school finished. That lasted for about two months while I looked for jobs; but it wasn't going anywhere so I came back [to Iceland] and started freelancing and doing other things.

Did you learn anything at SAE?

I can't say that I did. I mean, they had some theory courses and I guess it all sinks in somehow. My biggest disappointment for that year was the practical time; it was really limited because there was one studio and you had to book time far ahead. It was actually useful, because when you booked time you had to have a project-I had to go out and find someone. I actually found this great singer that I did some work with. You learn the hard way. You don't really sit down in a classroom and learn how things are. You have to pay attention, and if you're lucky enough to be able to watch someone work then you learn from being there. I've been really fortunate — for example, the projects that I did with Björk: just going to a session with a full orchestra for Dancer in the Dark. It was the first orchestral recording I had experienced, and I was the engineer responsible for all the backing tracks and sequencing. You pick up a lot seeing someone who knows what they're doing while working with 100 people. That's something really hard to explain to people.

It's ironic. It sounds like you learned how to be a freelancer in school.

Maybe I learned survival in the school. I don't know! [laughs]

I know with Björk on Vespertine you had a guiding principle, of "domestic music." I wonder if you could tell me more about how you derived that idea and how it guided the decision-making.

That was actually a phase leading up to and into Vespertine. They overlapped. Dancer in the Dark to the beginning of Vespertine was when the domestic idea was forming. The laptop is what triggered it. It was the end of the '90s and suddenly it was possible to do stuff on the laptop. I think, for her, it was appealing to be able to do everything small, take it with you, put it in a bag and do whatever you want with it. It was never exactly how we worked, as we carried a lot of gear around. But this idea of domestic music grew around the self-sufficient person able to compose, record, mix and do everything at home. During this time I had taken all the necessary equipment out of my studio to go to Denmark, where she was filming with Lars Von Trier [Dancer in the Dark's director]. We were in this big house and I had a garden pavilion with windows looking out at the sea with all the equipment there. While she was filming, I was working on the music for the score and we also started working on new pieces — all in the same house we were living in. That's where this domestic concept started happening. She'd come back after filming and work on new stuff. I don't know how much you've heard about that movie, but it was quite an intense and stressful process for her, especially not being a [trained] actress. Coming into the studio was a big relief. That was a shift of headspace for her and it was really important. The other part of the domestic idea was that you could create music out of anything around you. You could pick up a piece of paper, you could play around with it in the microphone and make beats and then cut it up in the computer. Go into the kitchen and find some things to make sounds with. It's a microscopic approach — really zooming into the waveform, cutting a small piece out, creating something new and combining it with another sound. I used to layer them on a keyboard and play all these beats that you would never come up with as a percussionist. That was a part of it. She would come in from the kitchen and say, "What do you think this would sound like?" [laughs]

Björk went on to record with other people, and I'm wondering why you guys didn't continue to work together? I hope that's not too personal.

No, not at all. We worked together for a long time, starting around 1998. In '05 or '06 I began the Bedroom Community label. I also wanted to focus more on my own music and projects. There was a point where I had to put myself on hold. It was around the time she was starting the Volta record. The intention was to keep working together, but it didn't pan out. We both wanted it to work, but it didn't seem like it was going to.

For scheduling or creative reasons?

Both, probably. We were in completely different headspaces — me wanting to go more on my own, her wanting to give me that freedom but not really accepting it. It was a bit of struggle, almost a breakup process. It was probably good for everyone because, after working together for so long, there's only so much you can keep learning and adding. It came to a point where I had to make a decision, "Is this what I want to do?" I didn't want to do that record. The difficult part about it was feeling like I had to close the door on a lot of people for a while. It was like starting from scratch after ending my time with Björk

But it's led to some great things. It must feel good to have that freedom and to pursue your music with Bedroom Community.

Absolutely. It was a good start.

Have you worked with philosophies like the "domestic music" with artists other than Björk?

I worked with this French singer named Camille recently, and she has these concepts for her records. The artist has to be into that, because it's really time consuming when deciding to go there. The luxury I had when I worked on the Björk project was being there from the writing process, to mixing and through the mastering. Björk and I worked together over a period of eight years on four major projects. It's a luxury to be part of the process, from when the first idea is born to two or three years later when it's finished. In the meantime, all these other ideas have come up and they go into the next phase. This is more than you get on a project that you plan ahead with the artist and go in to record for a smaller period — if you're lucky it's a few weeks, if the budget or schedule allows it. Something I try to do is break a project into smaller periods instead of saying, "We're going to spend two months making this record." I prefer to spend six months where the band and I work a month here, two weeks there and then two weeks there. That way the project is always in your system. Even if you're not thinking about it, it's developing. It gives me the opportunity to remove myself; to distance myself from something I've recorded. Then I come back to it and find something interesting and it becomes fresh again. I've been unhappy almost every time I've done something back-to-back; recording and mixing, for example. I try to encourage at least a week or more between, so I can come back and I'm not attached to anything on the tape anymore.

That implies that you're still making a lot of production decisions during mixing. I'm imagining, from the sounds you're using and the construction that's going on, that mixing is a lot more than tone and level.

It's as much about production as the recording.

Do you find that you're typically trying to get things pulled out during mixing, or are you adding during mixing?

It's anything from enhancing something that's already there, to stripping it down and arranging — going back and saying, "We have all these great parts, but actually they're in the wrong place." Or, "This would be stronger if we make this happen again." It's not uncommon for me to do that in the mix. I'm trying to push things even further. It's tedious and sometimes annoying, but when you have people recording, you want make the best use of their time, while not wasting hours trying out a million things. I'm happy to play around with it when they're gone. I can have some space to look at it from the other side. Sound sculpting and song arrangement is more or less open until the final mix.

How collaborative is the mix for you?

Usually not very collaborative. I do most mixing on my own, and then send people files. Or I'll bring them back into the studio so we can listen together and then have a discussion. My approach, for the last five or six years, has been to put down detailed stems. Sometimes that's the mix, but sometimes they get remixed, rearranged or edited. In Pro Tools you have so many tracks, just focusing it down into the sections is often something that I find really useful, in order to get an overview. Especially if it's a mix of electronic and acoustic instruments — everything is in a different acoustic space so you have to try to pull it together somehow. I find that I get a picture of it if I start by mixing things down as groups. Then I print the stems. I might go back, not to the original tracks, but only to the stems, if I need to record or work on anything. I prefer being left to it, at least up to the stems. I feel that's the stage where I can say to people, "This is what I was thinking."

People have been merging electronic and acoustic instruments for decades, but with your productions they seem to blur together seamlessly; especially on the more recent work you've done with your own album, Ekvílibríum. Ben Frost's Theory of Machines and Nico Muhly's Mothertongue also present a real defiance of the acoustic-electronic dichotomy. I'm wondering if you can speak about that from an engineering perspective, as well as a production perspective.

It's definitely something I've tried to do. Within all of those examples, the source material is always acoustic, or at least 90 percent of it is acoustic. Even the programmed parts might come from acoustic sources. As a programmer, and as a beat programmer, I always struggled to get the most organic feel. To make it breathe, make it feel played or, even if it's impossible to play, make it have this humanity about it. I got really interested in going into detail with the acoustic instruments and recording things so you could really feel close to it. You could feel the wood in the violin — not just the room around it, but the actual feel of the string or the player's breath. One of the only ways to do that is to layer things individually. I've actually experimented with doing it with bigger groups, but there's always bleed, which is fine. However, what you end up with when you've tracked everything in bits — which is not the typical chamber recording approach — is something that has a weird acoustic space, because there's no resonance between things. Instead, what I try to do is create reverbs or spaces around the instruments that make them blend together, and that creates an unusual blend. Sometimes I play it in the room, record it back and blend that ambience in. It doesn't sound exactly natural but that's partly where some of the sound comes from. Maybe there's a control freak element. [laughs]

Close mic'ing allows you maximum manipulation after the fact.

Which obviously Pro Tools has allowed us to do, and it's a risky thing because you don't want to lose the performance aspect. I listen to Mothertongue and I want it to feel like it's an album that's been played by a real musician. It's really important, so you have to use your instincts. When you're layering, you have to think ahead, "What's going to be in the picture when it's finished?" You leave space here or there. You're making a painting and you have ten glass panels. You paint something on one, then another, then a third, and son on. Then you put them all together and you still want to be able to see everything. Or, at least if you can't see everything, it blends through in the right way. You want to be looking at one picture. This is especially true with chamber instruments, or instruments used to being in concert halls; the intonation is [based on] playing with other people at the time and hearing the resonance between the other instruments. That's half the sound; if you remove that ambience, you have to be able to compensate.

Are there times when you think, "I don't want to work that way. I want to grab a bunch of ambiance and have things merge acoustically."

Yeah, it happens, but at the same time I feel if I do that and I don't cover my ass, then I will become frustrated and not be able to zoom in.

It seems you have a pretty good idea of what you want to hear in the final product as you're working.

That's true. I like surprising myself, but I usually have a pretty clear idea. That's why the mixing is important; because the mixing is where it actually all comes together. Sometimes the rough mixes sound horrible. [laughs]

Because there's too much going on and you haven't put the space on it?

Right.

Do you ever find that musicians are troubled or concerned about what they're hearing before the mix?

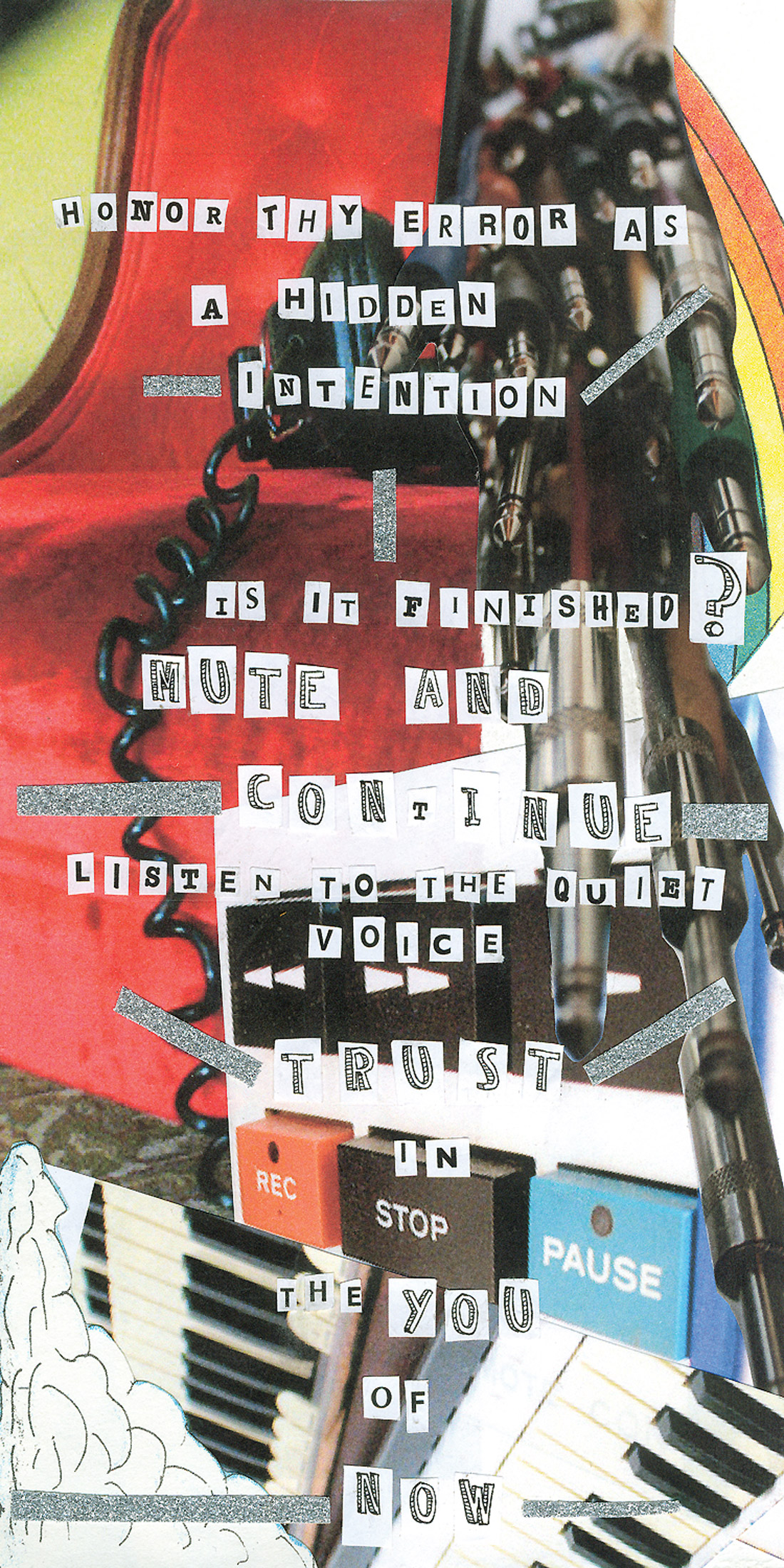

Yeah, that happens. But they have to trust. I guess all I have to say for myself is, "You like this thing I did and this is how I did it. Give me a little bit of space and I'll try to show you how it will come out on the other end." It takes time to establish and you have to try things before you actually know what works with each project. But, there's always a conversation. I always like to have the artist very closely involved when I'm producing someone. I like to work next to the artist and try to carry their vision through, even more so than mine. It's about them making their record, not me making mine. Then there the people I work with all the time and we create collaborative projects; but it's still their album or composition. Even Mothertongue, and some pieces on Nico's first album Speaks Volumes, were written with my approach to recording in mind — so that's flattering. Having said all that, I really appreciate and have deep respect for people playing in the room. I do a lot of that with sections of strings, brass or even bands, if I'm recording in a more standard way. I try to get them to play together.

You have a lot of the artists who you're producing come to Iceland and stay here. This is a far away, removed and different environment for someone who isn't from Iceland. Do you think this is lending itself to people making a new type of record?

It seems to be often the case. I can't easily explain why, but it's obviously a big decision to go somewhere; especially if you have to bring the whole band. You're committing to a new place and to not knowing what's going to happen. You could be stuck there, so you can't drive back and say, "No, it really didn't work out." Maybe that puts people in a headspace that's actually helpful. I haven't thought about it in this way before, but it makes sense that there's a certain dedication that you have to have. My idea when I was creating the studio was to build a space that wasn't like other places. I've been lucky enough to record in a lot of really nice studios. I've had the opportunity to try out ideas, test things and slowly bring them in here. It also comes from the design you start with; the shell of the house, basically. I decided not to isolate. You can hear the rain on the ceiling. I didn't want to build a floated room inside a room and make a dead airspace. I wanted to keep it organic. You can do it if you're in a place like this where there's not much noise. Also, because I wasn't building it as a 100% commercial studio, I only had to please myself.

As an example, let's talk about the Bonnie "Prince" Billy record, The Letting Go. It's regarded as a fairly new direction for his work.

I know he [Will Oldham] wanted a change of environment that would influence the recording, and also I think he's used to making records much more quickly than what we decided to do — played live in the studio and less produced. He wanted that, but he was also scared of going there. It wasn't easy for him to do.

How did his fears show up in the studio? Was there resistance to new things?

No, not really, but he was nervous as to whether or not it was actually going to work. He was totally open, but unsure if he would have a record at the end of it. It was the extreme opposite for me. Having had all those Björk projects that took years in the studio and then going to making a record in a really short time was fine for me; but it felt quite long for him.

How long was that?

Recording took about two or three weeks; then we came back for the mix and overdubs. I guess the process was maybe four or five weeks total.

I know you have people stay at your place while they work with you. How did that work out with Will?

That was actually prior to opening that part of the house. They were not staying at the house. There was a guesthouse down the road, quite close. They really liked that, being close to the studio. It seems to work really well when people stay at the house; especially if they come for a short time. It's intense, but it works out really well. It's exciting for us as well, to have a full house.

On The Letting Go

Valgeir is almost Kentuckian in his patience, insight and opinion. He lacks presumption. He asserts his expertise and fine tastes with a very welcome gentleness. Our time in Reykjavik with him was nurturing; we were a shambolic crew, to be sure, and our efforts were crystallized in a fantastic manner. Later, Valgeir and I met up at the Nile Hilton in Cairo to record singing for his Ekvílibríum record. I did not let the wildness of such a scenario go under-appreciated, nor did I let it overtake the task at hand, and Valgeir was uniquely similarly situated (or so he let it seem).

-Will Oldham <www.bonnieprincebilly.com>

_display_horizontal.jpg)