Teetering stacks of cassettes and CDs line every wall, occasionally broken up by whimsical relics, such as the bust of Elvis lamp and vintage board games. There are a lot of ideas that live in this room, recorded and archived in various formats. Stationed in a nest of equipment and instruments is DIY recording figurehead R. Stevie Moore, sporting a large, white beard and thick glasses. There is a lot of emphasis on "do" in the DIY term for him, with over 400 self-released albums since the mid '70s. Part of this work mentality perhaps came from his father, Bob Moore, a Nashville session musician who was featured on countless country and early rock recordings. R. Stevie witnessed a massive quantity of recording early on in his life and later went on to produce his own impressive volume of work. His technical setup consisted of what was available, and the technology was never a hurdle to jump over; it simply enabled him to record his songs. At first it was reel-to-reel tape machines with which he used a technique he refers to as "mic/line mixing," a variation of sound-on-sound recording. This method helped define his inventive sound, and his recordings retained a certain rawness and naïveté, complimenting his idiosyncratic songwriting. His first official release was Phonography in 1976, which was essentially a listening guide to his home recordings to date, curated and released with the help of his encouraging uncle. In 1982 Moore started his own distribution network, the RSM Cassette Club, which made his entire body of home-recorded work available.

Who is R. Stevie Moore?

I'm still a kid in his bedroom making music, getting close to 60 years old. I've never been a gear head. I've constantly been talked about as being lo-fi. Yeah, I'm the grandfather of home taping and lo-fi, but that's not really what it's about. It's the content — it's the variety.

How do you feel about the lo-fi label?

I'll take any label I can get — better than not having a label at all. I milk it for all it's worth. I'm not trying to be lo-fi. Ironically, a lot of my DIY (approach? style?) came about from trying to rebel against what my father was. He was the session guy, doing four a day with this mega-income and a swimming pool in the backyard. [But he was] totally dysfunctional and tense. I had a horrible childhood, so maybe that was something to break away from, into my cocoon of DIY.

What about the millions of people recording in their bedroom now?

I was doing it in '72. People say I'm influential, but I don't think a lot of people in their bedrooms [now] know who I am, unless their big brother had my records. I don't know — it's generational.

Is it a lot easier to be a home recordist these days?

It's almost too easy. Whether you make it on the computer or on this [taps fingers on a cassette], the point is, you have a stage. The Internet itself is a stage that anybody can be on, and I love that.

What about aspects of the Internet such as digital distribution? Some of these new models of band website membership are like your cassette club.

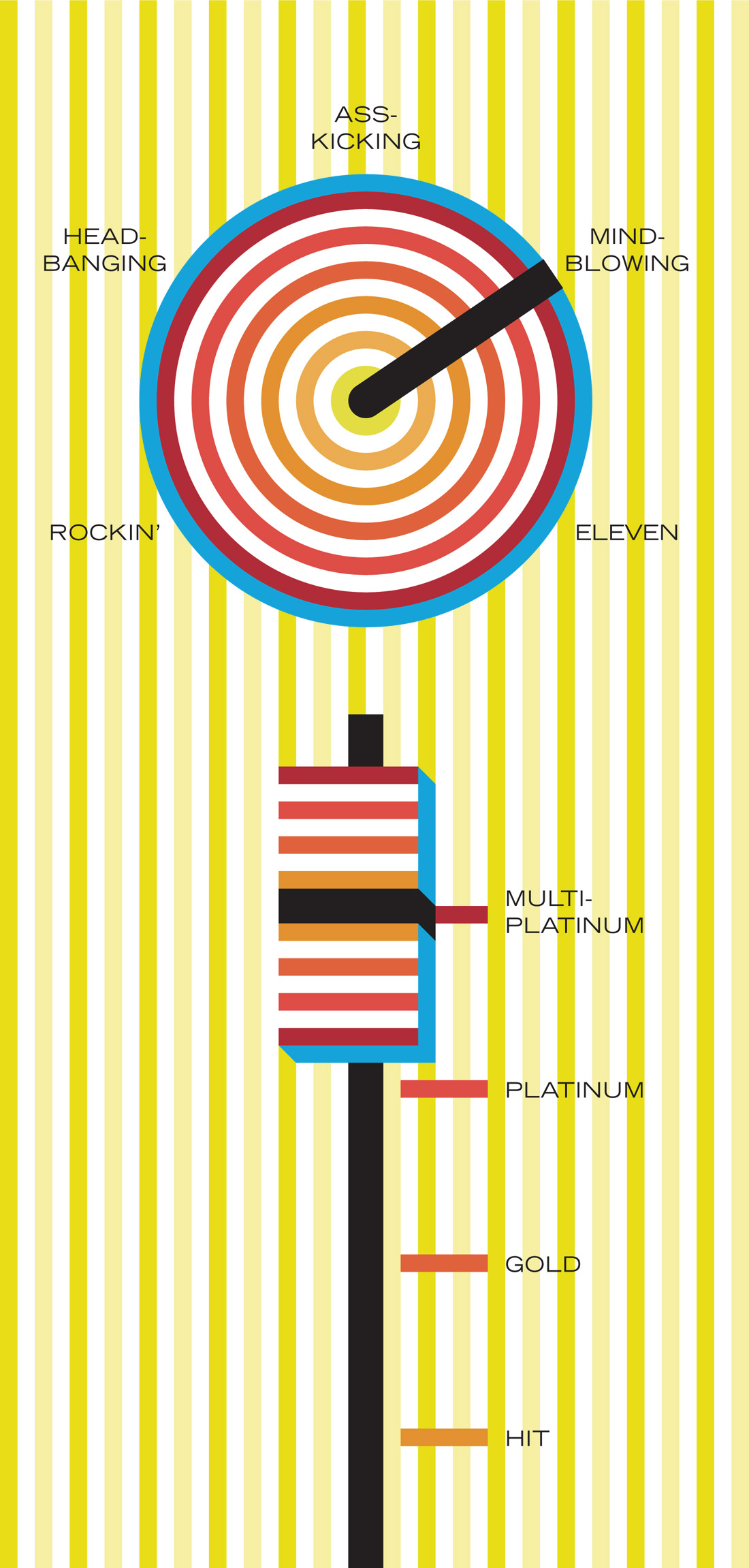

I've been slow to get into that, but I am finally starting to. I've always had my store with my music available online — everything I've recorded since 1966 — to the point where I have way too much product. But it's mainly [cassettes and CDs] to sell and ship through the postal system, as opposed to [downloading music] directly: "You want this new song I just recorded? Buy it for 99 cents!" I'm still not really into that and don't see the big deal. It's part of the public's hunger to get things immediately. Not only have I allowed every one of my recorded works to be available, which is a no-no, but I've also crossed the genres of music. I am not only an artist, but I am a guy who has his own label with various artists — all me. There's not one tape of heavy metal and then one tape of my soft stuff. It's all like radio shows. Everything I've ever done is like that. It's got to be a variety — I'm all these different groups, and everything I've ever recorded is available. A lot of people say that's artistic suicide because you scare people away, and sure, people are overwhelmed by the quantity — that's worked against me. I need an editor — that's part of my byline.

Have you ever wanted a producer?

I've dabbled in that through the decades. Ironically, it's just now happened in the biggest kind of way with Don Fleming. He was part of that Nirvana, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr. [scene] and he had a group called Gumball. He produced Hole's first record [with Kim Gordon] — before Courtney Love even met Kurt Cobain. We met at Maxwell's in Hoboken at one of my gigs because he was friends with Jad Fair of Half Japanese. We got together, I signed a contract with a little production company and we went in the studio to put down 12 songs with the band — there I was with a producer. It was really frustrating, because he wasn't capturing the band live like he wanted to. The band is too sloppy for that. It would take forever. It's against the grain of R. Stevie Moore. I have a bad habit of saying, "That's good enough — I'm not going to labor with this. How hyped does it have to be?"

Is it difficult for you to record outside of the home studio? Is it uncomfortable?

Not uncomfortable, because I am experienced and can do anything — whether it's playing in a Ramada Inn or doing disco music. I've done country music, Grand Ole Opry, punk rock — you name it. I have no problem working with other musicians. Again, I'm not a perfectionist. Don Fleming was playing the producer's role, having to crack the whip. "Let's try one more. That was close. Guys, can we do one more?" But I'm not a big discipline guy — I'm Mr. Quantity. I'm in the process right now where it's driving me nuts trying to finish this promised new record. I haven't had a new CD since last year and my little handful of fans is going crazy — "When? When? C'mon!"

Can you talk more about your recording process? Did you teach yourself recording?

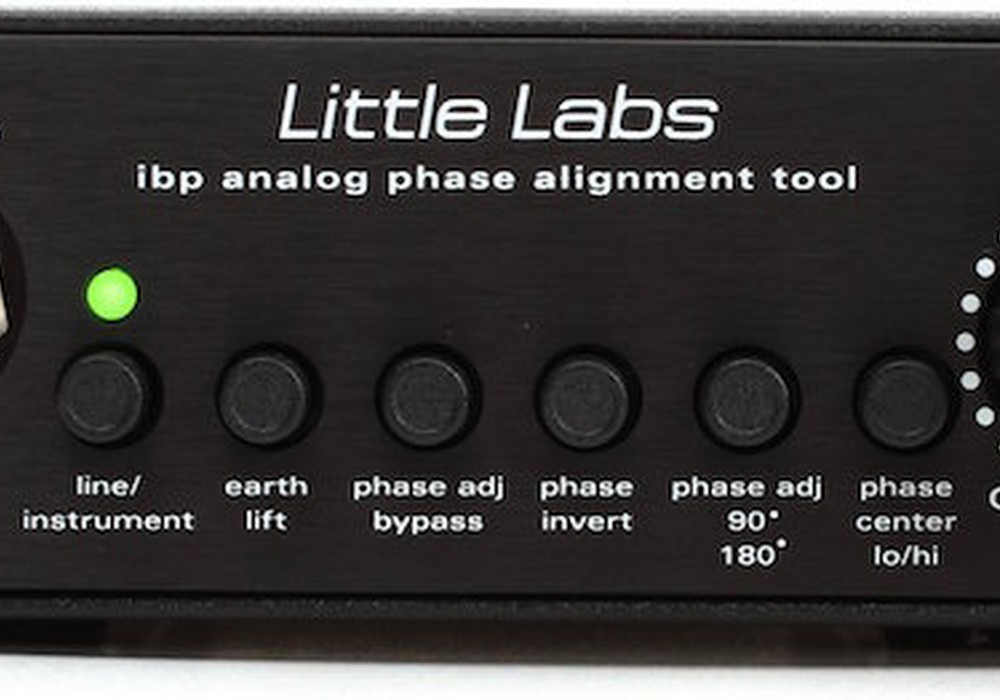

That's probably the best and biggest part. If there is anything I am proud of, it's being self-taught long before multitrack. I hardly ever was multitrack[ing]. I didn't have access to four tracks like the legendary Teac 2340. I had regular 1/4-inch stereo home consumer tape recorders. They had a thing called mic/line mixing. That's the most important part of my music, and I hardly ever even talk about it 'cause people don't really understand it. They're thinking of the Portastudio [where] you've got four, eight, 16... "How many tracks ya got?" I used two stereo tape recorders — cheap, good ones (Teac, Sony, Akai). Mic/line mixing meant you could record two separate sources simultaneously into one deck. The front had the mic inputs, no board. I was never a gear head as far as getting compression and EQ. It was direct. With guitar I had stomp boxes, but it was always 1/4-inch plugs. You could put stuff in the front, and then line in on the back with separate level controls, so that's how I overdubbed. Mic/line mixing — I got really good at that. I did the impossible and the unthinkable. I mean, add it up — all the vocal parts and all the instrument parts — 10 to 12 parts. They are all generational, if you know what I'm saying. I kept going back and forth bouncing, but that just adds tape hiss. The things that were recorded at the beginning of the process could be lost or buried by the time it's was done — but I got good at it. I didn't have Dolby or dbx [noise reduction]. I had a little Echoplex that helped with vocals, but I didn't have any way to compensate for going from generation to generation to generation. So some of the things recorded the first time were then re-recorded six, seven, eight times, which really tends to make it brittle. I got really good at knowing that newer things were going to sound better, and that if you're not careful they'd be too loud. I would always bring the old stuff up and the new vocal would be recorded at a low, low volume to compensate. You can't go back and remix. Once you do it you are stuck with it. But that's why I was so prolific — I got so good at it I didn't have to worry about being stuck. I didn't say, "I have to go back to that." I would just do that overdub. Left, right, back forth — I did a million variations on that whole theme. All that stuff was part of the DIY lo-fi. Forget the modern stuff. Forget "cyber" and Pro Tools. Forget recording studios with multitracks to the ceilings and 2-inch tape. Forget the Portastudio, which I have here. [Although] I had my little period with the Tascam 424.

When did you switch to that?

The late '80s. I was a latecomer.

Did you prefer your mic/line or sound-on-sound mixing?

Not necessarily. This was better because it was multitrack. I guess I gradually got away from mic/line mixing with reel-to-reels, and first used it in tandem with the reel-to-reels. I made some records that were of terrible quality on purpose with two Marantz cassette decks. I wanted that "shhhhhh." No mic/line mixing. Talk about ruining the quality — "This deck is going to record what's coming out of the speaker on this one." Some of them are just hideous and I love that stuff. That adds the quaint charm to it.

Often when I listen to music I prefer the demos, rather than the finished polished product.

The content, that's right! That's always been part of my thing. I'm sick of people even talking about demos — all of my work is demos. So what's wrong with demos? They're recordings. It doesn't mean they need to be perfected with sheen, polish and reverb. I've gone through the whole thing of trying to remake some of my home recordings, and there was something lacking. They sounded amazing, but they were forced and they weren't inspired. It always takes away. There are some things that are improved, but there are more things that are lacking. I am the king of demos and think people prefer them. If you are a music fan, you don't worry about it. I've loved working in studios, but it's a whole different thing. Now people say, "Why don't you go over there and record?" [pointing at his PC] I'm just starting to dabble with that, but even that is kind of cramped. This is like an old school computer — 12-track workstation. [Turns and pats the Akai hard disk based workstation he currently uses].

How often has your setup changed?

It's constantly evolving, but not quickly. I can't afford to upgrade and I'm not really interested in having the latest and greatest. The ultimate would be Pro Tools. I wish I would've had it 20 years ago. I'm to the point where I love working at home, but wish I could have one other guy to engineer for me. I'd rather someone else sit here and let me get out there with the mics and guitars, and he can capture whatever I do. Pushing record and running over is fun, but it's a pain in the butt. But in retrospect, that's what makes it so quaint and charming, because we are breaking the rules.

In terms of recording techniques, there are a lot of weird sounds in your music. Did those just happen or did you intentionally sculpt them?

Well, all of the above — but what you're bringing up is very important as far as happy accidents. I've always been a proponent of that. That was a big thing when I moved up here. Robert Fripp of King Crimson and Brian Eno were big on that as a way of creating art itself — of spontaneity and happy accidents. Unplanned brilliance that happens — it's a visionary thing and you can't explain it. It can't be taught. But I've done that too — sometimes you hope to almost create a happy accident, which means it's not an accident at all. I don't go back and try to polish anything I have done. So all my music is a bit sloppy and a little off kilter. "Goodbye Piano" is one of my most famous pieces of work, and I can't explain how it happened. It wrote itself. You don't set out to do something like that. It vomits out.

Are the sounds sometimes the inspiration?

Yeah, that can create the groundwork. The latest thing to happen to me is working with other friends just writing songs. Not recording. We do record, but it's not underground or outsider. It's just like taking a little course in school. Like a mathematical game of numbers and letters. Get a blank piece of paper. Don't play an instrument, don't sing a thing, just write "B, B minor, E" — we don't know what it means — just write it. Then repeat that. Play a game with letters and the song starts to write itself. I've been loving that. These melodies suddenly come. Doesn't it seem like I've been over-anxious, looking for the Hollywood success story? But be happy with what you are. For me, it's just paying the bills. It's not the glitter and gold of it all. It's been tough to even survive day-to-day. We all go through that struggle. I was thinking I'm such a unique pioneer — whatever that means — of home recording. But everything I have ever done, all the different stages, these reels and the Portastudio and then this Akai digital recorder — it's really no big deal.

It's just a means to get the music down?

I was thinking, "Doesn't everybody do this?" It's true, but not true. It's more about what my sound is — my content. It's not the means to devise content, it's the content itself and whatever kind of artist I am. There's no lo-fi and there's no hi-fi.