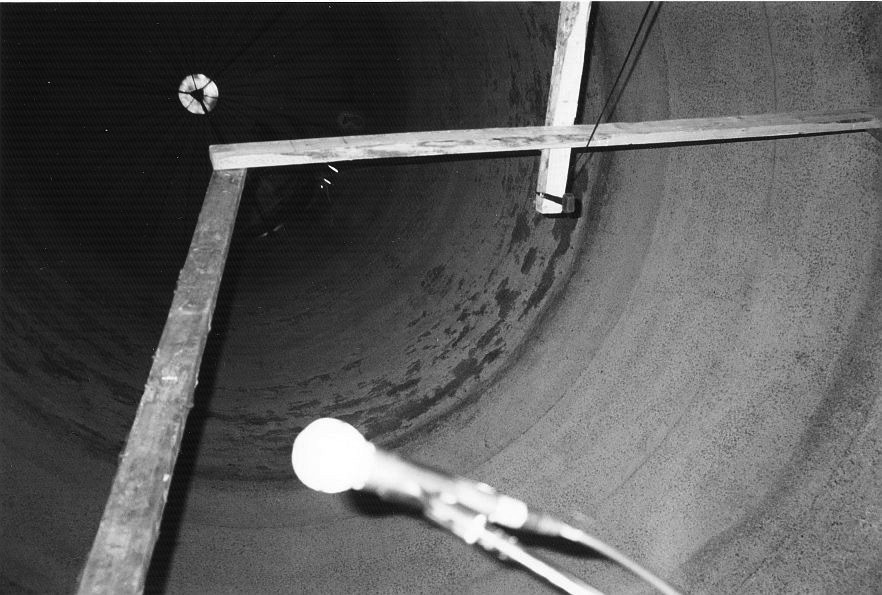

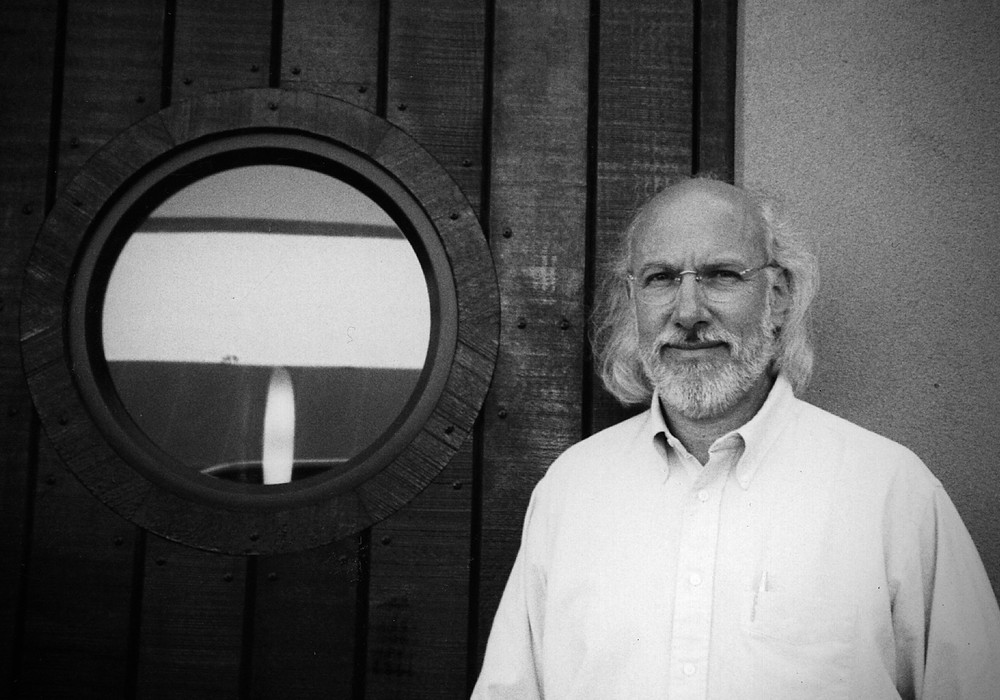

Tony Dekker is the man behind the Toronto-based folk/ambient/atmospheric rock of Great Lake Swimmers, which Mojo Magazine has aptly dubbed "ambient zen Americana." His 2003 debut album, Great Lake Swimmers, was recorded in an abandoned grain silo not far from where he grew up in Southern Ontario. In addition to the amazing natural reverb of the tall, metallic silo, the recording sessions took place at night and contained a bed of droning crickets and other field insects which Tony had no choice but to leave in the recordings. The combination of this production with Dekker's intensely haunting and emotional songwriting made for an album that completely blew me away — one that I listened to obsessively, that not only appealed to the part of me that loves pure, honest and melodic music, but the minimalist and experimental side as well, the part of me that loves exploring and embracing accidents. His 2005 album Bodies and Minds was recorded in a church, and 2007's Ongiara was mostly tracked at Ontario's Aeolian Hall. Different spaces seem to be important to Tony.

It seems like you use the organic room reverb of actual spaces. Did you do any reverb processing afterwards?

We tried to stick to the room sounds — that was the whole point. Not on the silo recording, but in the church recording there were a few instances where we had to enhance something like a minor detail here and there for continuity. But the whole point was to use the space and the sound of the space. With the church it was the same thing [as the silo] — we used a lot of different types of microphones at varying distances. We spent more time mixing than recording, that's for sure — at least double. I'm becoming more and more concerned with technical performance, but that was almost secondary to playing and capturing.

With the silo recording, what were your ideas about the insects in the background?

It was more of an accident than anything. I didn't go out there with the intention of making a recording with background noise and stuff. When we listened back after the first day we realized [the insects] were on every single track that we recorded. I thought about just scrapping it and trying to find somewhere else where there wasn't any sort of noise. But we decided to keep the tracks we recorded instead of trying to EQ out the noise or get cleaner takes. All that stuff was getting into the recordings — the guitar tracks, the vocal tracks — all of that stuff.

Did it grow on you?

It started to raise more questions to me about recording — how and where, and environmental sounds. It's become kind of an obsession now. At the time it was an accident, but now whenever I think about recording I think about it in those terms, about how place and space are the most important starting points.

Did you record just the guitar and vocals there? Or did you bring some of the other guys out?

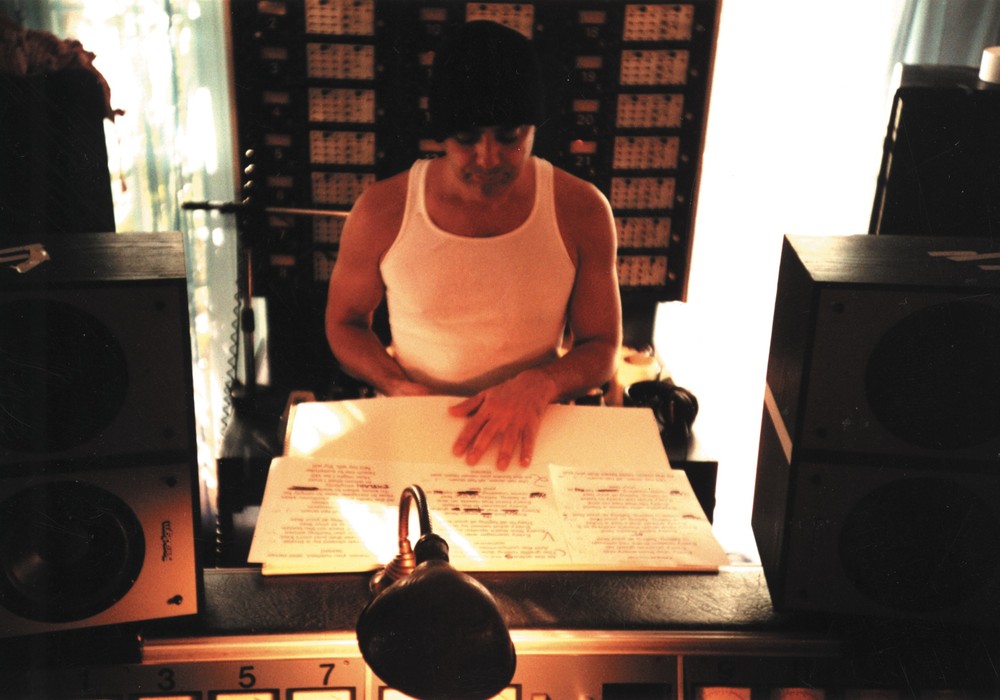

We basically recorded all of the guitar and vocal tracks. All the acoustic guitar and vocal tracks, including the vocal overdubs, were done in the silo. And then we worked on the record for about two years after that actually. I was working at a full time job so we could only work on the weekends. I have little to no knowledge of how to engineer sound so I had to work around Victor Szabó's schedule.

He engineered the album?

He's a Toronto native — basically, at least at that time, more of a drum n' bass kind of DJ. I knew he'd be a good person to work with. But it took a long time. Not only were we limited by our schedules, but we had so much material to go through. On every take we used about eight microphones. "Oh, this guitar take didn't sound quite right. I could do a better take. Can we save that one?" So we'd have eight guitar tracks and then trying it again we'd have another eight tracks and maybe an overdub would be another eight. So, you can see how it starts to pile up. Same thing with the vocal takes — we had the whole thing rigged up. So there was a lot of decision making in the mixing.

Then did you go into a studio at that point, for other instrumentation? Drums?

We continued to use this portable setup that we had in the silo to basically go where we needed. I had a friend who worked at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto and got us into some of their rooms to record where they had nice pianos. I was able to get a few friends together to add some stuff to it there.

You recorded to a Roland [VS-1880] hard disk recorder?

Yeah.

So you'd just bring that around to your friends?

Essentially, yeah.

I also read that you guys sort of had a bit of trouble with the owner of the silo.

...