I have been privileged twice now, while interviewing studio owners for this magazine, to have encountered true mavericks. People whose views on the current state of "The Music Industry" have been so passionate and forthright that I myself have left the interviews a stronger, wiser man. The first time was several years ago when I interviewed Walter Sear of Sear Sound. The second was when I recently visited The Magic Shop, a major independent recording studio located in the SOHO neighborhood of Manhattan. Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, The Magic Shop remains one of the few full-service rooms left in NYC. The studio has a rich history, having hosted Butch Vig [Tape Op #11, #115] and Sonic Youth in 1991; Interpol and Coldplay in 2007 and 2008; cutting songs with Lou Reed and Suzanne Vega; remastering the entire Rolling Stones CD catalog; working with numerous Grammy-winning bands and singer- songwriters; restoring over one hundred CDs for the Alan Lomax Collection on Rounder Records.

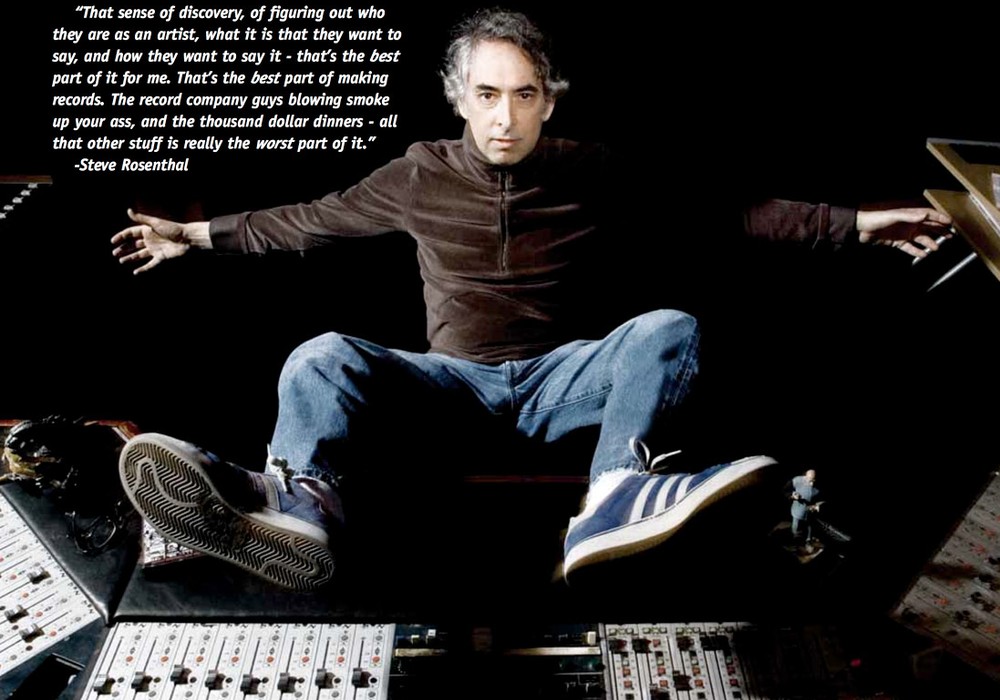

Three-time Grammy winner Steve Rosenthal is truly an experienced, gifted engineer and producer. The Living Room, the premiere singer-songwriter club in Manhattan, which Steve owns along with his wife Jennifer Gilson, is celebrating its 10th anniversary also this year. Steve was very generous with his time and very candid in his often brutally blunt assessments of where the music business has gone wrong over the many years. Due to space constraints, I unfortunately had to eliminate much of the raw interview. I would have liked to include more of Steve's remastering efforts — particularly his work with the Rolling Stones' catalog. Alas, something had to be edited out. I think you will find that this is compensated by some very interesting history and a whole lot of passion about recording and music — and about eliminating the bullshit in order to make a real connection with a real audience.

You became involved with recording in the mid-'70s when two friends of yours landed a development deal with Columbia Records.

I was at college in New Paltz with two friends from the Bronx, where I grew up. It was 1974. I left school to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. I was interested in music, had started playing guitar, and my two friends got a development deal. They got studio time in Boulder, Colorado. The studio was owned by a guy from the band Firefall. We drove out to Colorado to cut their five-song demo. One of the guys had a great time while the other one was really freaked out by the experience. I ended up working on the record with my friend, the guy who was not freaked out. I really enjoyed the process of figuring out what to do and what not to do. I enjoyed being in the studio. I also enjoyed the idea that when you were in the studio, it seemed like people were very unguarded and they were forced to reveal their "true identity." If you're going to make a record and you're going to be genuine about it, you have to reveal who you are. That was really intriguing to me — as much as the musical and technical parts, actually. The notion that people strip away a lot of the bullshit and try to achieve something of value when they are in the studio intrigues me to this day. Now it's thirty-something years later and I've met a lot of really interesting people and seen them in very revealing ways — sometimes really great, sometimes incredibly bad — but not a lot of bullshit, not a lot of pretense. So I got home from Colorado and borrowed some money from my friend, Richie Berger, to pay for engineering school. Back then; there was only one school — The Recording Institute of America — in the basement of Studio 54, a studio called ODO. They had recorded Steely Dan and a bunch of other great records there. We got to go in the studio once a week for four weeks for an hour and a half each time. That was my class. In 1974, engineering was not the respectable career that it is today. Now they have schools like Full Sail, and you can tell your mother, "When I grow up I want to be a recording engineer or a producer." There was nothing like that then.

How did you get your first recording work?

Herb Abramson was really my mentor. He was one of the founders of Atlantic Records. He was the mentor to a lot of really great engineers over the years. I went to the Yellow Pages and looked up "Recording Studios." The first one alphabetically was A1 Recording Studio. I called and said, "Hi. I've got a little bit of experience and I want to learn how to be an engineer." It happened that he had an opening. I went down the next day and he offered me a job. I was his apprentice for no money for almost a year. After a year, I started getting paid a little bit.

What did you do to support yourself while you worked for free?

I drove a taxi. Flexible schedule, but driving a taxi is a crazy job and it's a tough way to make a living. I also did market research — surveys and things. When Herb started paying me, I moved to Manhattan — around the block from where he was located. I lived across the street from Miles Davis, who used to come out every Sunday in his bathrobe and hold court. I got to talk to him a number of times — he was really sweet. Herb had one of the Atlantic Records' consoles — it was tube, with rotary pots. It also had the old school-style faders — when you brought them down, things got louder. Herb was a gifted and complicated guy who taught me a lot. You had to follow his methodology — about where...