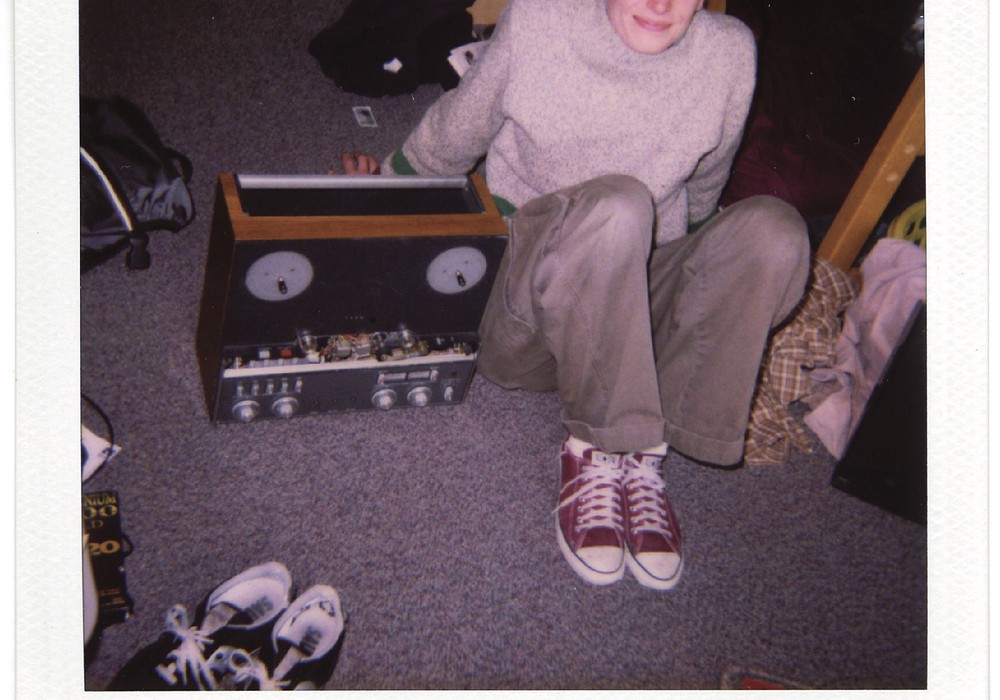

Björn Yttling is standing in my studio manhandling a Moog. He's not getting what he wants out of my old Realistic MG-1 that I've had since high school, but that's no surprise as it's been in the corner for years sucking up dust. He's got a determined look on his face, searching for a way through the noise to get at this beautiful melody that's he's working on. In about two minutes the old bird is singing sweetly — it's a minor miracle. Peter Björn and John — Peter Morén, Björn Yttling and John Eriksson — are at my place for a few days, rehearsing songs and demo-ing for a new record. They're winding up two years of touring for the ridiculously successful Writer's Block. You know, the record with that infectious whistle-laden song, "Young Folks"? C'mon, even your mom has heard it in the supermarket. We've got keyboards and drum machines on every surface and drums and amps strewn about. Even the piano is mic'ed, going into the PA with a ridiculous amount of reverb. They're completing songs and solidifying arrangements. Over the course of three days I hear the same set of songs played fast,slow,beats changed, different instrumentation and different feels. Björn has the band looking at the songs from every angle. It's a rehearsal-heavy pre-production ethos. Björn tells me that he's psyched to be in L.A. because the time difference keeps his cell phone quiet so he can work.

Björn is a powerhouse keyboard player/arranger who has been at the core of several great Swedish bands. He's played and toured with The Caesars, Nicolai Dunger and Dungen, as well as producing records for The Concretes, Shout Out Louds, Robyn and Lykke Li. With a fantastic ear for what makes a song tick, records that he works on feel timeless yet sound like they've been beamed in from another planet at times. Never losing the thread of what weaves serious hooks together, his arrangements are deceptively simple but can turn on a dime and head for Sun Ra territory. Just check out Yttling Jazz, his side project that sounds like Raymond Scott bouncing around inside a Mingus pinball machine.

Somewhere in the four days that he was in L.A. — in between Björn heckling bands at the Knitting Factory and getting 86'ed and banned for life from one of Steve Aoki's scenester Djnights-we sat down in my dining room to talk it up.

When did you start recording? Were you in a band?

I was on this Jeopardy-type TV show when I was a kid, and I won a trip to Copenhagen. I changed the trip to become a 4-track cassette recorder.

They just gave you some money and you spent it on a 4-track?

Yeah,and a pair of good AKG headphones.It was a Fostex cassette recorder, but I had used a Tascam [Portastudio] before — at music school.

You went to music school when you were in high school?

No, even before that. When I was 12 or 13 the school had this Atari 1040ST and a Tascam Portastudio. Later they bought a Roland D 50 [polyphonic synthesizer] and that's the first stuff that I started messing around with. Then I got my own 4-track. I just had a mic and was doing tape to tape — no turning back. Well, I guess you could go back one step!

How old are you?

33.

So you're not like some people your age who basically have never used tape?

No, but I was into synth music. When the MIDI thing opened up it was great — you could do more stuff. I did [MIDI] on the Atari or the Commodore and would put it on tape and then record the voice. I then I went to high school with Peter [Morén] and I guess I continued recording on the 4-track.

So you were just recording yourself at first?

Yeah just me and a friend — songs that we wrote.

How did you start recording and producing other people?

I moved to Stockholm, where you could meet more musicians, and I got to play with this guy Nicolai Dunger — kind of the first proper gig for me. I was working in studios as a keyboard player for producers like Pele [Almqvist], who produced the Hives, and Jari [Haapalainen], who produced Ed Harcourt. So I was working and I realized that I didn't want to go around playing live all the time — it wouldn't be a fun life. I figured that if these guys were producing records then maybe I could too; I started co-producing with Jari, easing some of his burdens and learning what to do. I was arranging too — strings and horns. I had learned that before — I write sheet music. So I started with our first record, Peter Björn and John, in 2002. Then I recorded a girl called Marit Bergman — really the first record that I produced. It was a hit in Sweden. At that point there wasn't much indie rock in the charts — it was much older stuff and more slick stuff. Marit kind of broke the indie thing in Sweden. At first I didn't have good budgets, or any at all, but I did it anyway. I tried to take on bands when I didn't have work — to get them to pay for studio time — and I would produce them for free. I kept working all the time. At this time I played with The Caesars. That's where I got money from — touring with people. I toured the States and Europe. I co-produced some records with Jari, who became really successful. We did a couple of gold records in Sweden. Prior to that I had some extra work, like a piano teacher, but around 2002-2003 I just kind of quit.

How important is preproduction for you? Do you do a lot of that?

I don't really ever record anything before I go into the studio, but I rehearse a lot with people. I do pre rehearsals! That's the important thing! Getting the song structures, the keys with the singers. Sitting on the sofa singing — not being in the rehearsal space.

Just at their house?

Yeah, it sounds different singing in a mic. You tend to take it up all the time, because you can't hear yourself when it's low.

You mean you actually changing the key of the song?

People tend to move the key up in a rehearsal situation, but when we sit down on the sofa I can hear that it's much better in another key. Usually, I like to sit with the drummers. I like the drums and the beats and the rhythmic patterns to be following the songs. I know if I have that I can get the bass and the other stuff going. It's the voice and the drums first and then we go into rehearsals (usually) if it's a band.

What's the process for figuring out whether something should be acoustic or electronic? Especially with the drums?

I usually don't do electronic drums. I never use soft synths or samplers. I like it when you don't really hear what instrument is playing. I like to mess around with acoustic sounds and take electronic sounds and run them through amps.

I would have thought that you were using drum machines at some points because the grooves are so solid.

I can't say I don't use it, but I usually add on stuff that you wouldn't maybe put on. Like the hip-hop trick — I put a wooden clap on the snare. Or you damp the strings on a guitar — you hit the wall or ceiling. Or you put some different notes on the snare. It could be a synthesizer that I play for a brief time — maybe something like that.

It's not like you're putting sequences together, doing programming...

Sometimes I chop it up. It's great to have the ability to move stuff around in the computer.

I know that you try to get as much you can to tape first and then transfer.

I almost always do that, depending on the project. The Peter Björn and John record we did on computer because of the fact that I don't have a tape machine at my studio. We wanted it to be more direct and dry and we didn't want to take away the edge from the hits. If you want to do that, stay on the computer because tape takes away some of the transients. I just recently bought an [Universal Audio] LA-3A. I didn't have a compressor at my studio that I liked before so I didn't even use compression. It's a nice one. I had used it in other studios before and liked the LA-3A. I always kind of just ride the fader when I record in my studio.

As you're recording?

Yeah, during a take. Take this chorus separately and just turn it down. I don't really like compression. You just put it on and you think it sounds good, but it's not really adding something.

How important is your home studio as part of your process? Do you find yourself there as part of every record that you do?

Yeah. I like going there after tracking for listening and editing. Listening is very essential with bands — getting people in the right corner so we're together and know what we want to do. Otherwise people will just come up with any crazy idea of an overdub, like strings everywhere or different guitars, pianos, organs. "Where do we want this song to go? This is what I see we could put on and this is why I want it put on." So we sit and listen. It's good for improvising and doing crazy stuff to be in a smaller studio. You don't have to run many meters to change the mic. You can plug stuff in really fast. I like being in my studio because I've got all the synthesizers too, but it's also faster than being in a proper, big, great studio. It's more about the process than the gear. It's more time consuming. "Where is that monitor buzz?" I'm not really a mixing guy, so I don't get stuff that [other] people have recorded. I'm happy when I'm remixing so I can hear what people did, but I don't really do that.

If bands bring in demos, do you use them or do you just start from scratch?

Sometimes, if it's something that's really sounding great. Maybe if it's more electronic stuff I'll use it. But I kind of want a vibe on the whole album, so I want it to be done in the same room. Usually I pick out a few instruments for each record [which] I want to use. It helps to create a framework for it. Or pick out some instruments that I won't use. "I won't use a Hammond" or "I won't use an electric guitar" or "I will not use a Spanish guitar." Make things easier — decide this is a maracas record and not a tambourine record!

It sounds like setting limitations that make sense aesthetically becomes more important.

You can always get any instrument to sound like what you're after anyway. Say you're not using synthesizers on a record — you can always get a distorted marimba to sound like an 8-bit synth. There are ways around it, and that's where it gets interesting for me. You can find new ways of getting the same feeling as the old way.

Before you came here, we were talking about "good" gear versus "crappy" gear. You asked me to take the big amps out, leave you the little ones and to drag out the "crappy" drum machines and keyboards. But we've also been talking about how it's important to have a good piano. Take drums for example... is it important to have the drums tuned really well?

Naw... doesn't really matter. Sometimes I'm after a really full, jazzy, Gretsch tom sound — then I get someone to tune toms for me because I can't do it myself! But usually I just take anything and hit it and if it sounds great I can build a song around it and then I can use it on other songs on the record. It doesn't really matter — it could be a crappy piano too! We usually don't like the well-tuned, great new drums with no flaws. I'm more into the crappy sounds. If you can get a bunch of crappy sounds together and make it sound great it's more fun. It's so easy to get good-sounding instruments recorded — anyone can do it. Well, maybe not anyone, but it's easy. It's always interesting, those small sounds when you listen to records. "What's that? Why did they put that in the mix?" But it sounds great and it kind of makes sense. It's always the odd bits you want. It's so boring when you hear a great intro and the full sound comes in and it's destroyed — the song is ruined. If they just kept the intro going it would have been great. Like some Young Marble Giants' song. But then they come in like the "proper" drums — I hate that. I want to keep that as the bearing elements of the song. The odd bits should be the main bits, the other stuff is just to kind of get it together. Put on some sub bass or some synthesizers — that's easy. I wouldn't like to start with the good-sounding stuff and then try to get the odd bits in. That's not my way of working.