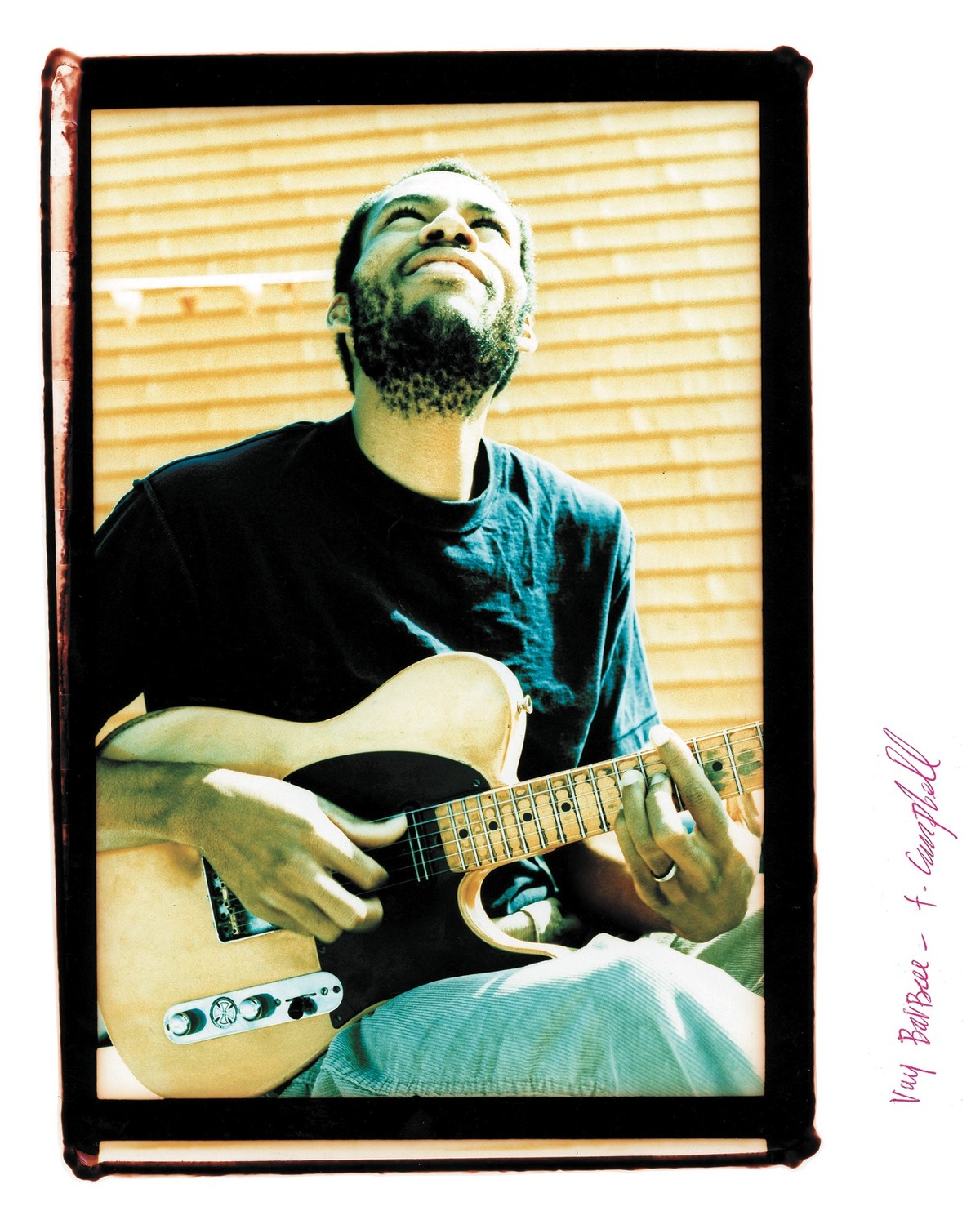

A few years ago, I was at the winter NAMM show, the insane dog and pony show of musical madness that it is. If you've never been, it's hard to imagine the spectacle of it all; death metalers bumping into the smooth jazzers hanging with the Goths talking to the bluegrassers while the aging rockers and their aging ex-stripper wives compete for face time with aging grey hairs who still run the mom and pop music stores that supply the high school marching band. Dweezil Zappa and Lisa Loeb bump into Stevie Wonder and Gene Simmons, while Herbie Hancok and Bernie Worrell do an impromptu jam down the aisle from Michelle Shocked and Dusty Wakeman, trying to do an acoustic set next to Joe Satriani and the drummer from Poison signing autographs. I just go about my business, there because the business of giving away Tape Op to you for free demands it. Then I saw Ray Barbee walking down the hall, and I was a bit starstruck. Ray is a pioneer of early skateboarding, the days when it transitioned from vertical ramps and pools to the streets of the city. The confines of pools and ramps were replaced with the open expanse of the city and it's ledges, stairs and handrails. Ray was a member of the original Bones Brigade along with Tommy Guerrero. The Bones Brigade was put together by Stacy Peralta and CR Stecyk of Dogtown fame, and the early skate videos they made with young skaters like Tony Hawk are classics of the genre. To watch how smoothly Ray skates is to understand how he made the transition to playing music and why he's evolved into playingguitar in a jazz idiom, informed by hip-hop and punk. As it turns out, I shouldn't have been starstruck. Ray is totally down to earth and a super nice person.

We've stayed in touch over the years and Ray ended up buying my old Allen & Heath console and Fostex 16-track to augment his Digi 001 and Tascam 8- track set up. Through Ray I met Thomas Campbell who did this months' cover art and runs Galaxia Records. Check out the interview with Tommy G. in this issue, as well as the CD reviews section for some other Galaxia & T-Moe tidbits.

Starting out:

"I started on a Tascam 246. That thing was great. It was kind of a glorified 4-track 'cause it had a mixer. It had more sophisticated routing and four outputs. The EQs were better too — they had shelving or peak, and there were more frequencies. That was pretty cool for a 4-track. I got that from my friend, Monet, who used to go out with the Arabian Prince from NWA. She used to do music but got into insurance and had all this '80s music gear lying around and she knew I was into music so she let me use it. So she let me borrow that and a DBX 160x and then a Tascam DA- 30 DAT. So, I had a fun little setup and I used that to do my first EP, Triumphant Procession."

"What happened too was when the guys at Galaxia started talking about releasing that album, they're like 'Let's get you in the studio,' but the way I did stuff was I'd go skating during the day and then at home at night I'd have ideas and start cataloging them and recording them. So I started thinking if I spent time in the studio and I knew I was under the clock, man I don't want to put myself in that situation. So I told them just give me some money and I'll get one of those new digital workstation things. Maybe it'll be an upgrade in sound. So I did a couple songs on it. It was a Roland VS-880, I think it had some data compression on it. So right away I was just like... I let a buddy listen to one song and he's all 'What is that?' and I'm all 'It's a guitar.' It sounded like a dulcimer or something — it was just so brittle. So I got rid of that and with the money I got from that, the first thing I got was the little Fostex R8, which was cool. Then I wanted to upgrade to 1/2-inch, so I got a 38, but that was tough because the transport was kinda loose. I had that for a little bit. Then on Thanksgiving one year, I was recording my buddy's band so I got my 38 and lugged it over to this church. I pulled an all-nighter and when I got home — at that time, my wife and I were living on the second floor, and I was like 'Oh man, I don't want to lift this...' I was gearing up to bring it back up, so I set it down on this little brick platform area and it wasn't balanced so it fell on the top and it pushed the motor into the inside of the deck. So that's how I got a Tascam TSR 8. Then I broke down and got Pro Tools and an 001, and then an 002, so now I'm, trying to figure out the merger of the two. Either starting on the tape and flying it into Pro Tools and then addingtoit.OrsometimesI'vetriedittheotherway. I was so bent on just getting my guitars onto tape, on my TSR-8, but since the stuff was already in Pro Tools, I recorded it onto tape and then played it back into Pro Tools. So I had the original and then I'd fly the tape in and I'd have to line it up and it was crazy because the tape's stretchin. I'm seein' where some points are on and a lotta' times it's off, so I had to get in there and cut it and then get it all lined up. It was tedious...."

The sonics of software:

"I have noticed a difference in platforms too. For my new album, I went out to track with Doug Scharin in Chicago, who plays with June of '44 and Rex, and he had just gotten Digital Performer and we tracked on that. I had to get a computer after that. So my friend Lance [Mountain, another member of the Bones Brigade] who does The Firm, the skateboard company I ride for — I was doing music for The Firm video at the time and I just got back from working with Doug, and I was telling Lance if I had a computer, I could get a lot of stuff done. So he got me a computer from the art department one of the guys was upgrading — a G4 and a monitor. So then I was trying to figure out what platform to go with, so from spending that time with Doug, I was like 'Digital Performer seems cool,' but it was way too many options. But the sound card I got at the time was a used 001, so I had Pro Tools too. So I'd go back and forth on the same soundcard, and when I was in Pro Tools it just seemed closer to my tape deck — just two windows. Just simpler, not a lot of MIDI options. But it seemed like the Digital Performer was cleaner, more hi-fi, and it was almost like the Pro Tools tone was a little less hi-fi, a little duller, which I dug. That's kinda my issue, things being too sparkly."

At this point Larry, Ray and I started talking about how many mixes we'd heard in Cubase and Nuendo that we thought sounded really good and some of our friends who raved about the sonic quality of the Steinberg platforms. It got pretty techie and we'll spare you the details.

Larry wanted to know how Ray managed to get what sounded like more than four tracks on the first EP. "Oh yeah, I definitely had to get creative about bouncing. That's what was so cool with that 246, is the EQ really made it easier to get the right tones when I was bouncing. I never tried to go to the DAT and then back — I probably should have. The thing is, I was never trying to get eight tracks. I think at the most it was six. There was a lot of cutting things out to put other things in, a lot of different things on the same track. That's what was fun, when I think back on that. A big part of the fun was not having any big expectations. But it was also, 'this is what I wanna' do, this is what I have, now how am I going to pull it off?' When I think back on those recordings, I was definitely more adventurous, more experimental. But now, I got all the tracks I need..."

Our next tangent was about limitations and how they're good things. This gets Ray started on how much he still likes working on his Akai MPC, a very limited machine. Then we talk about the Hank Shocklee piece in the last Tape Op. Says Ray, "With my four track and even my eight track, if something's going on, you mean for it to go on. You're not saying, 'Let me just put it in, see how it sounds, maybe I'll mute it, whatever..' You don't have that option, if it's going in, it better be toeing its line."

Then we got to talking about how great The Meters were, and how that kind of playing is so rare now. We talked about making a lot of the big name producers today enter a contest where they all have to make a record with a Mackie, a 4-track and a bunch of SM-57s. The Dogma school of filmmaking comes up next, and we discuss Dancer In the Dark, the movie with Björk, one of my all time favorite movies. Next we profess our mutual admiration for the Cowboy Junkies Trinity Sessions. Larry was taking notes — expect to see more on these subjects in the future...

One of the things I really wanted to talk to Ray about was how skateboarding as a teenager and continuing to skate as an adult (he's 34) had influenced his life and his music. I know I have my opinions on how skateboarding made me look at life. Almost a decade ago, I did an interview with Ian MacKaye of Fugazi for the skateboard mag I worked on at the time, and he had a similar view — "I think skating was a really, super- important part of my life, mostly because it gave me yet another extremely good opportunity to redefine the world that I lived in." Ian goes on, "Most people, when they walk down the street, see the sidewalk and the street, they see a wall, and a hill up against a parking lot or something. But from my point of view, and all skaters' points of view, you see everything different — concrete is a whole different language to you. It just gave me an opportunity to redefine the world I lived in, and that process of redefinition can actually parlay itself into any area of life. It's about reassessing what's given and making it work for you. That's what skating is all about."

When I asked Ray about this, he had this to say, "There are so many similarities. Skateboarding, you can do it yourself or you can do it with your friends. Music is the same way. I love the creativity part of it — there's no rules. Music's got implied rules because they've figured out a system for it, but you don't have to go by that. It's whatever moves you or whatever you want to do. And I love that about skateboarding. There are no rules, nobody can tell you, 'you can't do that.' They can say they don't like it. But they can't say 'you can't do that.' I like that in both things, you can do something that you've never heard or seen before."

"The other thing for me personally, is that I always loved music. When I was young AC/DC and Angus Young were my heroes. Every other week, my parents would take me and my brother and sister to Rainbow Records in San Jose where we lived then, and we could get one tape. I'd always get an AC/DC tape. I had every AC/DC tape out and one of those was a live album, so I remember playing that in my little boom box pretending I was Angus. But the thing is, until I got into skateboarding, I didn't know anybody that had a guitar. Once I got into skateboarding, the friends I made, they all played in punk bands, so all of a sudden musical instruments were accessible. I'd hang out at band practices and when they were taking a smoke break, I'd pick up the guitar and get them to show me chords. It made it accessible, and I'm beginning to realize that's the key to anything. You can sit around and wanna' do something, but unless you're able to actually get to it... So it made it accessible and it turned me onto so much new music. When we were skating ramps, you had the boombox going with Minor Threat, Bad Brains, The Faction [Steve Caballero's band, another Bones Brigade member], Social D, Vandals — and then we started getting into Metallica and Slayer, and then my buddies started learning to play those songs. Then skateboard videos turned me onto bands like Dinosaur Jr. and fIREHOSE. I love how the two are so intertwined, because it's part of the experience and the culture."

I really wanted to get at the creative process though, so I prodded Ray a bit more. " To me it's all coming from the same source. I wanna' do something neat. How do I pull it off, whether it's on my skateboard or it's on my instrument? How am I going to swing it? What I will say is that skateboarding has made it so that there's a form of rejection that I'm used to. I can get over it because of the learning curve of skateboarding — going weeks or months trying tricks and not pulling it off. And then, for whatever reason, one day, boom, there it is. What it takes to do that applies to learning an instrument or recording or whatever. That not- being-easily-discouraged kind of thing."

I tell Ray about the quote from Ian above, and Ray laughs. "Yeah, that's right. We're plagued. I'll never look at stuff the same. Me and my buddy Matt Beach were talking about that, 'Do you realize that we're gonna' be 60 years old, driving down the street and being like 'somebody's gonna' be able to jump off that rail.' It's true, that's what skateboarding does to you. And unconsciously, I know that's what gets brought into everything I do. I don't try and sit around and figure it out, but I know that's what's happening. The way I approach things because of skateboarding gets applied to everything I do. I see that all across the board. I see that with my friend [movie director] Spike Jonze [who got his start as a skateboard photographer and skate video director], [actor] Jason Lee [who's first skate video was directed by Jonze], you name it, guys who because of skateboarding just went for it and in a lot of cases, brought something refreshing to it. One thing I've noticed about skaters too, is that you can't tell them 'You can't do it,' they've gotta' find out the hard way. If they have a desire to do something, they're going for it. It doesn't matter if they have the time or not. There's a big part of that that I admire, but you also have to have wisdom to know how long to go for it, you know what I mean? You figure that mentality coupled with talent, it's gonna' get in someplace."

Larry and I wanted to know how Ray went from the typical punk rock skateboard soundtrack to the instrumental, jazz influenced music he's doing now. "I played in punk bands and had my time of being able to crank up my amp. What I love about music, too, is it opens you up to so many different genres. All of the sudden, I find myself digging country guitars or getting turned on to my pop's collection when early on, I'm like 'I can't hang with this Motown jazz stuff.' And now I'm like, 'This is the best stuff!' The more you get influences, the more it becomes your vocabulary. For me, whether it's skateboarding or music, I'm always just trying to push myself. So it comes from that. I like power chords, but then I wanted to learn minor seven chords. I can pinpoint the times I heard something that really changed how I heard things — the first time I heard the Pixies, Tortoise, the first time I heard the Minutemen and fIREHOSE. Mike Watt, man — I always thought bass was for lame guys. Then I heard Mike Watt and I realized the bass was something to be reckoned with! And then that turned me onto James Jamerson. But lately, I've been wanting to rock, so we'll see what happens..."

Ray and I have been talking the last few months about maybe working together in the studio on his next record. I want to know why he'd even think about going into a studio when it initially seemed like such a bad idea to him that he turned to home recording. "What's happening is the reality of being a jack of all trades, but master of none. I'm so busy, that nothing gets done if I try to do it all myself. I've gotta' relinquish control to people I trust. I'm really excited about getting some ideas done and then going into your studio and at least getting bass, drums, guitar — at least get a foundation in about a week — and then go back and fill in the gaps and get a friend to mix. Then I can still be productive and get something to come out. From my EP to the album was like four years or something. It's just time to switch it up and work with some other musicians too. I always do programmed stuff and some drumming, but I really want to have a lot of live instrumentation. I have so many talented friends like Chuck Treece, Doug Scharin, my friend Matt Rodriquez — hopefully I'll talk Tommy into playing on a few things. As much as I say I don't want any deadlines, if I have them I get stuff done. There are so many skateboard videos that are still on the back burner because there's no deadline."

And on that note, Tape Op is way past it's own editorial deadlines, so although we had another really interesting tangent about Ray teaching the kids at skate camps how to play guitar, I need to wrap this up and send it off to Larry and our copy editor, Caitlin. Later skaters.