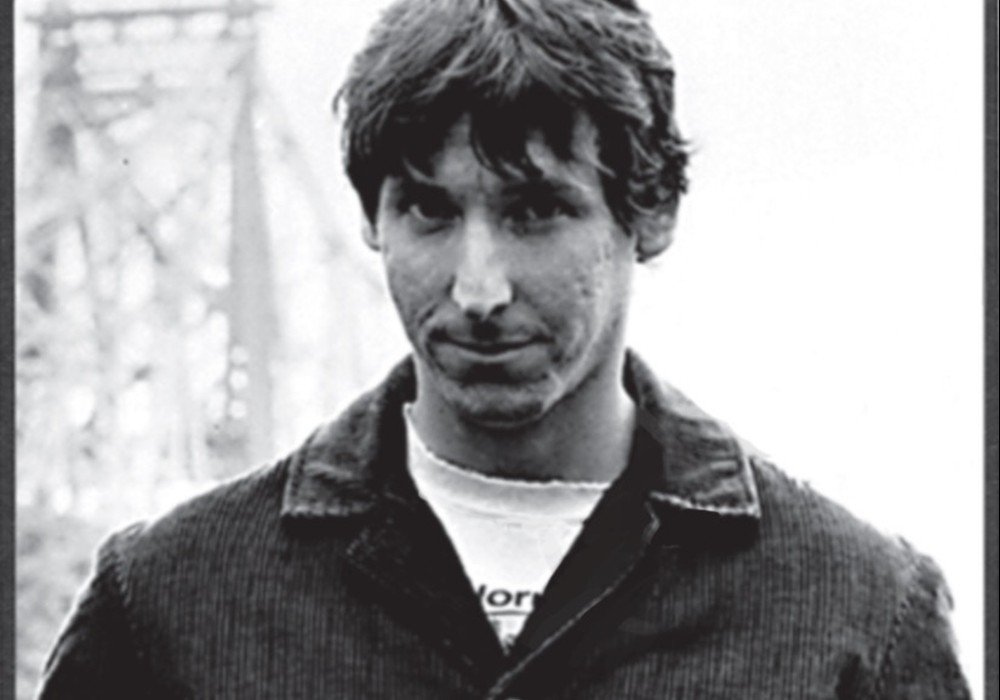

Jon Brion is well known as a session musician, record producer, solo artist and now, with the work he did for Magnolia, a scorer of films. In his world, all of this is equally important and interrelated. He's worked with artists such as Aimee Mann, Fiona Apple, Robyn Hitchcock [Tape Op #17], Grant Lee Phillips, Elliott Smith [Tape Op #11, #38, #118] and more. He's done a lot for someone in their mid-30s, and from his perception of what constitutes a great recording to how he's found himself doing the work that he does, you can tell that he's put a lot of thought and all of his energy into being where he is today.

How do you get the session jobs and production work that you do?

The only reason that people get work and are working on records is because somebody has heard a record that you've done something on and they want to pull off a little of that. If you show up and you're a jerk, they'll never call you again. That's it, that's all there is. There's no other secret that is being withheld, for you or for anyone else that does it. People are going to hear some tracks that you've done and go, "I think that's cool, I want to work with that guy."

And it seems like you've got to do 20 tracks for every one track that somebody hears.

And it's not always the thing that you think. It's not the thing you're doing that you think the world is going to go, "A-ha! Mr. Crane is up to good work." It's going to be something that somebody's playing and the person they're going out with hears and happens to go out drinking that night and says, "God, I heard this amazing thing today." It's going to be the b-side of something or something that was never released — it's just a cassette. That's the reality of it.

The secret that the old engineers don't tell you is that your best work is never going to be heard. [laughter] Something that you put a lot of energy into might just be totally buried or never released.

I remember reading some things with session musicians over the years — they would grumble about how it doesn't matter what you do because it's going to be mixed too quietly or the mix of the whole record is going to not have a groove whatsoever. You work on something that was really cool when you were there and by the time it comes out it's messed up. And lo and behold, it actually turns out to be true. As a session musician, I played on so many things where I just came home out of my head so happy about it [the session] and by the time it gets released it's completely watered down. They killed it.

Did you start out as a session musician or as a musician?

As a musician, I've always loved recording. As a kid, I was fascinated with tape recorders, I love everything about them — microphones, amplifiers, all of this was magical stuff. By the time I was 13, my dad had a friend who happened to have a recording studio attached to his house. There was this local hard-rock band recording — it was a 16-track recording studio. I went nuts. I was just sitting in the control room watching them overdub. I was 13 years old and realizing the significance of an overdub.

How it's piecing the song together..?

Yeah, and the whole notion of it. I totally got what it was and the potential of it and just looking at the machine and this big piece of 2" tape going by. It was the most massive piece of tape I had ever seen. It was the most monstrous, fantastic thing. I pretty much knew that I was going to spend my life being a musician by the time I was 7 or 8. By the time I was 13, I knew that I wanted to be recording. I had a stereo cassette deck and my dad had an old stereo reel-to-reel and I just used to do massive overdubbing, jumping between them. Ever since I was 13 I've had headphones on. I didn't have an amp so I used to overdrive the tape machine by plugging my guitar into the mic input. It was beautiful. A couple of years ago, somebody turned me on to the Lindsey Buckingham stuff on Tusk [Fleetwood Mac]. It was a very similar guitar sound.

There's that strange kind of dry, edgy guitar sound on there.

Yeah, and the other funny thing at the time was that I discovered if I detuned down to low D, I could play power chords with the fuzz with just one finger. I had this really strange...