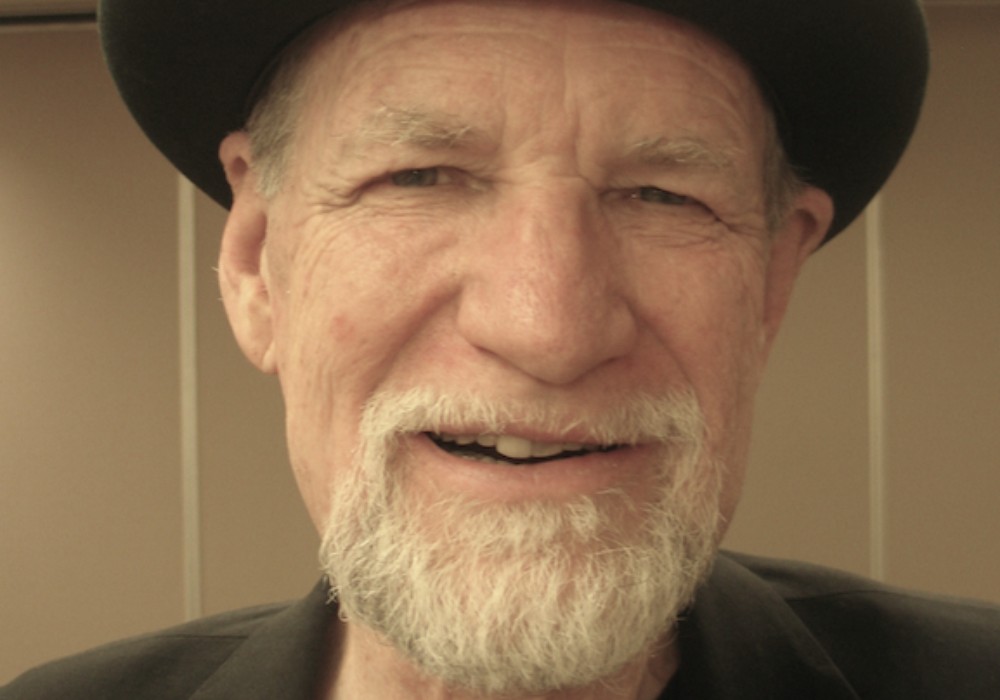

Establishing himself as one of Nashville's top engineers and producers, Gary has worked with Nickel Creek, Alison Krauss, Sarah Jarosz, Harry Connick Jr., John Prine, and even Dolly Parton. He is also VP of A&R at Sugar Hill/Rounder Music Records. I visited Gary at his private studio and home that previously belonged to Alison Krauss. In fact, Gary even helped design the studio for her.

What year was this studio built?

In 1998. We were ahead of the curve, in terms of home studios in Nashville. Back then we thought it would be used mostly for vocals; but with budgets where they are today, this is a full-on tracking facility now. [laughs]

How did you enter the engineering world?

My uncle is an artist by the name of Michael Johnson, who had a couple of hits in the '70s and '80s. As a kid, he was a big deal to me. He is a great musician and singer, who started out as a traditional coffee shop folkie, moved on to major label deals, had pop hits and all the trappings that go with success in that world in the '70s. As a young teen, it was magical and I wanted in. There were lots of great bands and records in the 70's that I was listening to; but none hit me as hard as Pink Floyd, specifically The Wall. I knew enough at that point to realize that what they were pulling off on that record was truly amazing. This would be a special record, even with today's digital workstations. I don't know how many times I've listened to it...

Where did you grow up?

In Colorado, outside of Boulder. I went to Colorado University for their recording program; but it was pretty basic and not fully developed. After a few years of doing that, I knew that I was going to learn much quicker in the real world, because it just wasn't run the way that programs are now.

In what way?

Well, even for us to round up a band to record would take an insane amount of effort. It's not like the music schools today where there are bands roaming the halls, dying to go record for free. They'd have a pair of mics, and then one would get stolen. There was limited studio time — all of the obstacles like that. However, it was a good, well-rounded education, in terms of electronics and production. Actually, the electronic music program was pretty cool. When I realized the program at CU wasn't quite there yet, I landed a year-long internship at the Eastman School of Music [Rochester, NY], where I had previously done a six-week summer recording institute program. To be thrown into that environment, with world-class classical and jazz musicians, was really inspiring. I had an amazing year recording jazz ensembles, tuba quintets, operas, symphony orchestras, and everything in between. Not at all musically where I thought I would end up, but it was stereo mic'ing to the hilt. Every variation of stereo mic'ing you can imagine, because all of the halls were mic'd different. I learned a lot about the honest tone of the instrument in the room, as well as what that sounds like.

It teaches you to really listen when you're putting up a pair of mics.

Yeah. Some of the recordings had close mic'ing as well, so you learned how to blend things in. A lot of that translated into the more acoustic/roots oriented music I do now, such as trying to honor true dynamics while maintaining an individual's tone. With everything I've done in Nashville, it's always been about making it have impact, while trying to retain some dynamics. I've also had the luxury of working on music that isn't chasing mainstream radio, so I haven't had to fight that battle too often. Obviously I've done mainstream records where we're definitely shooting for radio, but by and large I've been fortunate that I haven't had to play the loudness game.

You aren't pigeonholed per se, but you definitely have a field you work in of acoustic-based Americana music. How'd your career end up towards that path?

I was assisting at a Nashville studio called Nightingale, working for an engineer by the name of Joe Bogan who made a lot of good records in L.A. with George Benson and Seals & Crofts. He was a great guy to learn from. As an assistant, I got to work on everything that was coming through the place, from Randy Travis to B.B. King. All over the map. In the late '80s Chuck Ainlay came in to record the [Strength in Numbers'] Telluride Sessions featuring Jerry Douglas, Béla Fleck, Sam Bush, Edgar Meyer, and Mark O'Connor. It was fucking unbelievable to assist on that after all of the other stuff we'd been working on. They took two days just to get sounds. We spent a whole day trying to decide between 15 or 30 ips [inches per second, tape speed]. It was the first record, for me, where tone was just as important as the song, performance, and everything else. It had been about speed and quantity, up to that point.

Nashville is especially known for speed.

It's probably because it's expensive when you've got a room full of guys. Back then, 15 or 20 years ago, when a lot of guys we were working with were double or triple scale and studios were going at prime rates, you had to move quickly. Sometimes that meant that tone and dynamics became a secondary thing. Then these guys came in and made tone and mic'ing techniques a priority, and the music benefited from it. Honestly, from that moment on, I knew exactly what I wanted to do. I bought the same monitors Chuck was using. Everything about that session was what I wanted to do, going forward.

Chuck's a great example. He's on a quest for fidelity, but also a very personable guy.

Chuck's the best. He's fairly typical of the Nashville vibe, in that if you need help, he's going to help you. If I'm going to record an artist that he's worked with before, I can call him and ask what mic he used. That's very typical Nashville.

What led to working with Dolly Parton?

She was cutting some demos at the studio, and it was a huge deal for me to even get the demos. I hadn't engineered much. I was the assistant, so when no one was there I'd mix every night until the sun came up, trying to figure out how to do things. Somehow I got to cut a demo, which turned into another one or two, and then she asked me to cut a record. I'd never done a record — I didn't know how to make a record! It's a lot different when you're assisting; it's a lot of paperwork, setup, and just trying to stay ahead of the engineer. But to take a record from beginning to end... I had a big budget.

What album was that?

It was a Christmas record [Home for Christmas]. I had no business working with her at that point. I was in over my head all the time for most of my early career. I was scared to death. I think I met Alison on the second record I did with Dolly. We brought her in to sing harmony vocals. At the time, Alison was looking to make a change, sonically. From working together on the Dolly album, she apparently liked what I did, and hired me to cut tracks for the Alison Krauss and The Cox Family [I Know Who Holds Tomorrow] album. I was just supposed to work for a couple of days, but by the end of that first day she asked if I would stay for the whole record. I think we made eight records together after that, mostly with her and Union Station. It was a daunting undertaking, to dive into a new genre without a firm grasp of the fundamentals of the music. The band was amazing with that. They took me in and made sure I got educated on all the classic records. They knew all the great musicians and singers. Of all the records the band played for me, the ones that spoke to me the most were those that Bill Wolf engineered. The Tony Rice records — Manzanita, in particular. That record pushed a lot of boundaries and influenced a generation of young musicians and engineers. I still look up to him. He's a badass.

You obviously learned a lot along the way, but do you feel you made mistakes?

Many... many. I still have never had the courage to go back and listen to that Dolly Parton record again. I found it on cassette about three days ago and was tempted to hook up the machine, but I thought better of it. The truth is that there are only four or five records I've made that I've been able to listen to and not get really depressed. I'm pretty sure anybody worth a shit would tell you the same thing. I think that's more a product of mixing records "back in the day" where there was no instant recall, no "version 12" mix, before it goes off to mastering. I think mixing was more of a performance back then — everybody had hands on faders, twisting knobs on the fly, and embracing commitment. That process led to a lot of magic, but it also meant that you could have gotten an entirely different performance the next week, or even the next day. It's hard to not look back and wish you could have done things differently. I'm currently re-mixing a record called So Long, So Wrong that I did 18 years ago with Alison and Union Station. It's a pretty incredible record, with amazing songs and ridiculous performances. That record was tough, because Alison wasn't used to hearing her vocal recorded the way I was recording it, with more detail on the top-end. She was also singing a little breathier, not quite as hard. Maybe it was because of the way that she was hearing it in the headphones. We were still trying to find our way as a team. It was too exposed for her comfort, so she consistently wanted to bring the vocals down in the mix. My fix to still make it heard was to make it wetter. Big mistake. Of course we hated it a couple of months from then. So now, 18 years later, I get to fix that. Or at least try to.

It's hard. Sometimes you just can't change it.

That may be the case with this one. I love the remix, so far. It's amazing how in tune and in time it is — without any digital manipulation. We worked so hard on those records. We all laugh about it now. These days it's like four takes because it's possible to make it work with a couple of passes.

How live were the So Long, So Wrong sessions? How much bleed was there?

Well, on most of those early Alison records, it was all about isolation. We'd cut a basic track and almost re-cut it from there. Getting a great track was really to lock in the tempo, because we weren't usually cutting to a click. It was just making sure we had the right tempo, and the right form. Pretty much we'd start from the bottom up. Maybe we'd go until we got a great bass pass, or whatever, and start doing bass repairs and re-cutting the instruments. It was a great situation, actually. There was enough time, and isolation, for me to really focus on tone. Not to mention the fact that every player had an amazing instrument and exceptional talent. It was shocking to me how much importance they put on sounds. If it wasn't a good day for me — if I wasn't quite hearing things right — she'd call it. She'd just say, "Hey, it's not happening today." For the first time, what I was doing was just as important as what the band was doing.

And it was a mutual recognition of that fact too.

Yes. In other cases, if the engineering wasn't happening on a rough day, you'd just fucking fight through it. It's money, and everybody's time is limited because bands are busy on the road. Obviously there are a lot more records that I do now (and everybody does) where tone is that important. But, other than seeing that with the Telluride Sessions record, this was new to me. They also talked to me a lot about tone, about banjo tone or upright bass tone. I learned a lot from every one of those guys in the band.

What studios were you working out of?

We were working at that same studio I used to assist at. It was called Nightingale, and then it became Seventeen Grand Recording. We cut some at Emerald [Sound Studios] and moved around a little bit, but it was Seventeen Grand Recording for almost all of it.

Was that by choice, since you'd worked there already?

Yeah, being a young engineer it was the one room that I knew really well. I knew where to put everybody. Each iso booth had a strength that suited either upright, vocals, mandolin, or whatever. Then we would come here, to what was Alison's studio at the time, to do overdubs. I mixed all over the place. Still, eighty percent of what I do today I learned from Alison and the guys. Alison and her approach to dynamics and space, her patience in making you wait until the third chorus to hear all those harmony parts — it's unlike with a lot of country, or pop, where everything comes in with the first downbeat. She serves the song, period. If it's a great song, and sung well, the listener will still be there with you.

I would assume that those records led to a lot of other people searching you out as well.

Yeah, it led to everything. There were other records that people sought me out for, but ninety percent of what followed came from [working with] Alison. The problem with having a particular sound that people like was that I'd get hired for that sound, even when I was trying to expand and do something different.

Who were some of the first performers to seek you out, based on that?

Chris Thile [Nickel Creek], Mindy Smith, and Gillian Welch. And then I did a cool record with Dixie Chicks called Home.

Dixie Chicks were much more commercially oriented. Was that a learning curve?

That record was actually more in the wheelhouse of what I had been doing with Alison than what the Dixie Chicks had previously been doing. The real learning curve was doing my first record on a DAW! We were using an early version of Nuendo, and I didn't have a clue what I was doing. I would be faking my way through the day, and then spend hours after they left trying to fix what I'd screwed up. It was a learning curve, dealing with strong personalities in a band that was living under that much spotlight and pressure. Plus they were making a record that was so different to what they had been successful at.

A lot of times too, the process informs the sound. If somebody comes to you for a sound but they don't follow the same process, you won't get the same result.

Exactly. Alison was such a brilliant arranger, and she left space for me to work with. Other people will come to me for how I approach depth and width, but if the production doesn't allow for it, it's not going to have the same result.

How did the Sugar Hill Records A&R job come about?

They had hinted at me doing A&R for them when we crossed paths during the Nickel Creek and Dolly Parton bluegrass records. It really didn't even cross my mind that that would be something I wanted to do. The truth is that I loved making records for that label. It was a family owned company; they were loyal and very good to me. The first Nickel Creek record we did for $24,000, and we sold a million, so they were happy. They found out that I had worked for free for a couple weeks, because with Alison and I, if you ran out of money you just kept going. It was never about the money. Good things follow good work. It didn't even cross my mind to mention to anybody I was working for free. A guy at the label found out about it and sent me a couple thousand dollars out of the blue.

That usually doesn't happen in the music business.

Absolutely. I'd worked for pretty much every label out there at that point. When they asked the second time, I was basically burned out from working 24/7 on records. Sometimes you find yourself in the studio for days on end just comping and mixing — countless hours alone. It was nice to stop doing that exclusively. I love developing artists. We all have those projects we're doing for free, just trying to get somebody off the ground. To me, this was going to be a prime chance to get in and do that, and get paid for it.

What year did you start?

I've been doing it eight years. It was a much different job ten or twelve years ago than it is today, for sure. It's nearly impossible to sell records with a new artist now. Your successes now are so small, and on such a different level. Back then, an act like Nickel Creek would carry the rest of the label, and that allowed the A&R people take chances. For instance, Sarah Jarosz's last record sold 60,000 copies. Eight or ten years ago it'd be a 140,000 unit record. It's just completely off.

How'd you become aware of her?

The parting words from the woman at the label before me [Bev Paul] were to keep my eyes on Sarah Jarosz. I went to the Telluride Bluegrass Festival and I was walking around in the middle of the day. I heard this voice in the distance. It was just so unique. It was obvious that she had it. Luckily she was coming to Nashville after the festival so I brought her into the studio right away to check her out a bit more, and we signed her soon after. She was 16 when I signed her. We made the first record during her breaks from high school (when she wasn't on the road), and the last two during her education at the New England Conservatory of Music. It would have been easy for Sarah to drop out of school when cool opportunities were presented to her, but luckily she stuck to her guns and finished school.

Have you seen her develop as an artist because of school?

Yes, for sure. She was exposed to so many different styles of music, and pushed in directions that she might never have gone otherwise. NEC is a world-class conservatory, filled with amazing musicians. At the same time, a lot of her growth can be credited to her experiences on the road, playing festivals with peers like Tim O'Brien, Darrell Scott, and Chris Thile. They've been with her from the beginning, and influenced her greatly.

How do you balance recording and A&R time?

It's a tough juggle, for sure. I try to focus on one aspect at a time — if I have a record, I throw myself into that, and vice versa with an important label client. Both parties have been really respectful of that. I'm very lucky. But yeah, any time I'm not in the studio, I'm working on A&R. There's always a ton of listening to do. In the last two weeks I think I've been out 11 nights to see bands at different venues, and I'm always going to festivals.

I was going to say that festivals are probably the best way to find artists.

They are. I can catch up with our artists who are there, and then look at new ones. Balancing a very demanding A&R job and making records... we know records are only as good as the time you can put into them. The label has been very understanding of that fact.

Has the A&R job cut down on the time you get to be in the studio?

Yeah. It also forces me to be more efficient when I'm in there. Plus, I have people I can rely on at the studio should I not be there. Right now Shani Gandhi co-engineers a lot of my projects. If I'm producing and engineering, it helps to have someone I really trust to turn the engineering over to. If I'm in that chair my natural instinct is going to be sonics, so it helps to be able to step away from the console and focus on the overall performance. It's a great team.

Well, part of their path is watching you work.

I'd say more so my job is learning from them. I was interested in Shani — particularly in her having worked for producers in completely different genres — because she brings something fresh to the table. These days it's not often that I'm in another facility and see how people are working. The records that Shani listens to are different than mine. I need to be turned on to new music. We're always trying to grow.

You've mentioned several times the pigeonhole you feel a little locked into. Do you ever wish you weren't locked into that and could make a Pink Floyd record or something similar?

I haven't felt that way for a long time because I've been able to branch out a lot more lately. But I definitely used to! It goes both ways though. I love making those acoustic records, but I'm still always looking at the other artists who I want to be working with. Here at my studio, the live room isn't big and I have no isolation. Whenever we track here, everybody's together. Maybe I'll move the vocalist in front of the console, or put somebody in the back of the control room, but I'm doing a lot more of making the leakage work. I did a record a couple of years ago that I loved, John Prine's Fair & Square. Luckily I get calls for that now, because that was a really rocking — everybody in the same room together — record. It had a real raw energy to it. That's what really moves me.

How did you get involved working with Nickel Creek?

It was Alison's manager, Denise Stiff, who told Alison about them after seeing a show. Again, it was obvious that there was something really special there. These kids were serious. Alison and I produced two records with Nickel Creek — Nickel Creek and This Side. I've also done a couple of solo records with band member Chris Thile, Not All Who Wander Are Lost and Deceiver. Deceiver was a great record to do. He played every instrument on that record, and it took us about a year and a half to make. What was interesting about that record is that he knew the sequence of the record before we cut it. We would start and complete track one before we would start a note on the second track. I heard some of it not too long ago. You could tell where we got tired of working on the fucking record all day long, because by song six or seven it's just a mandolin piece. We were so relieved to strip it down, because we were building loops and doing a lot of other stuff we didn't really know how to do. He'd never played drums before, but we bought a drum kit and four hours later he's playing on the record. I learned so much from Chris. Chris is the guy who I will send a record to when I really need feedback while I'm working on it. He's usually got a great couple of things to say that make all the difference in the world.

You touch on that a lot, learning from musicians as well as learning from feedback and collaboration.

Those are the only compliments that I can ever really take in. You'll have people say nice things about the record, but half the time you think it's just because that's what people say. But when musicians tell you that it sounds like their instrument, or sounds like them, or is exactly how they imagined it in their head — that's what excites me. You also start to realize how many sessions that they've done where it doesn't sound like them. Back when I started, things just got compressed and mashed into place. Acoustic guitars sounded like hi-hats. It's nice to present a full range of everything the instrument has to offer, and showcase all the intricacies of the particular player.

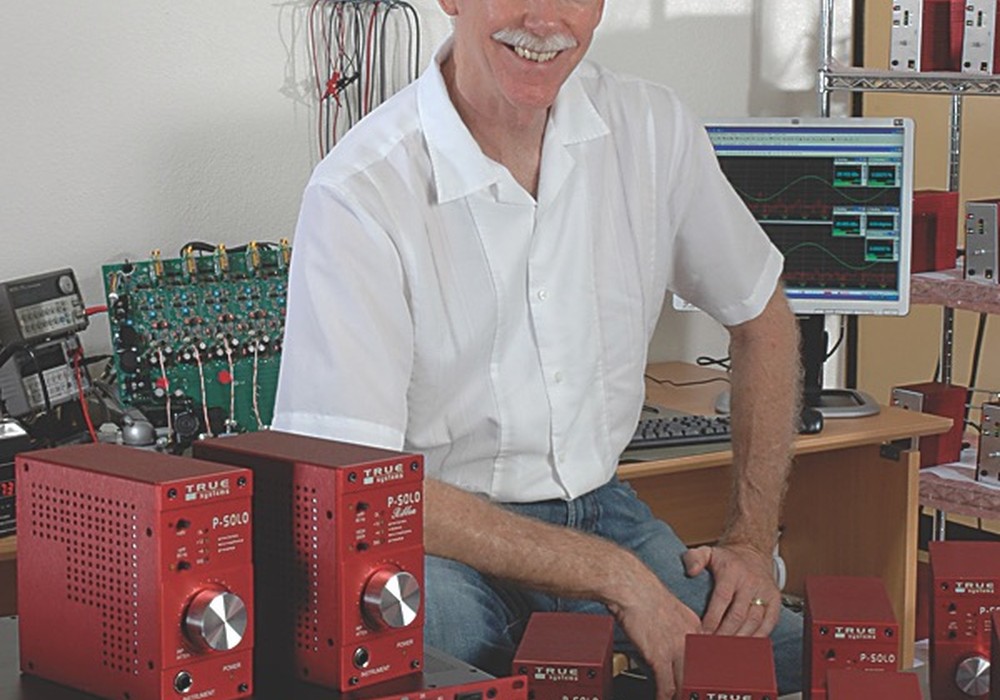

As far as mics, did you find anything along the way that helped you up your game?

I think the first, and biggest, thing was the [Neumann] KM 54s. I used them at Bill Schnee's studio — he had a bunch of them. I was sort of surprised, because it's just a small nickel diaphragm capsule. Everything up to that point was large diaphragm and more hi-fi. When I heard the 54s, especially in a stereo configuration, I flipped at the detail and presence with no EQ. I went through a couple of pairs of those and found a few pairs that I really loved. I think I get the most comments on the sounds I get with those mics.

Have you ever tried the Gefell m582 mic with the nickel capsules?

I've got a pair of those. I love those Gefells. The nickel diaphragms are great for low volume level detail. A lot of what I do is quieter. I'll even put 54s on the snare for brushwork or light percussion, like in a jazz setting. I've done a couple of sessions in New York with some great drummers, and they're amazing for that. I'd say that my only real love affair with any mics I've owned are the 54s. It was also always in combination with The Mastering Labs' Microphone Preamplifier.

You don't see those around too often.

No, you don't. The combination of the 54s with the Mastering Lab pre has always been great for what I do. Do you still rely on any of the same gear? Yeah, apart from KM 54s — and it's been talked about before — this wax box [custom Mäag EQ] that I'd mix through. Mostly I use the Mäag's Air Band on top end. The sub band gets used every now and then. Before I started using that, the first thing that I'd do on acoustic sessions (on every channel) is lift up the top-end to try to find the air and upper harmonics. It helped me a lot to do that earlier in the process so that I knew how it affected everything, like reverb tails and sibilance. Before I started having EQ on the 2-mix bus, I'd get to mastering and I'd be surprised by everything. I liked it because it crept in above sibilance and anything ugly. For tracking, I've been going through the Mäag 500-series. Their EQ2 module is a lot more controllable.

That brightness was my impression of Alison's records.

They were such great players, and all had unbelievable instruments. Lifting the top-end brought out the upper harmonics, the attack of the upright bass, the detail in the mandolin solos... hearing everything in the instrument. It was always the fine line of not being harsh.

A lot of the time, if you're into production, engineering gets pushed to the side. I don't get the feeling you're doing that.

No, I'm not. I'd hate giving up mixing. For me, that's the part I love the most. I love the energy of tracking, and I love being part of the vocals. But I love what you can create with a mix. I couldn't give that up in my career, but there are a lot of guys in town I'd love to have mix something I've recorded just to hear their take on my tracking sounds. Records require so much time and energy — it's all-consuming. Now I'm doing it piecemeal, coming in at nighttime but then I've got a gig to run to. I think anybody who has a job in this business today is doing multiple jobs, so this is nothing new to most people. If I had to say what I am, first and foremost, I'm definitely an engineer. I produce in slow motion. I have to be paired with the right artist, like a Sarah Jarosz; she's as much a producer as she is an artist.

I guess you're the one who signed my friends Black Prairie to Sugar Hill?

Yeah. I'm definitely always trying to push the label with some edgier stuff. It really started out as a bluegrass label, and there's less of that now, basically due to straight up economics. If you can't support it and do a good job with it, if records aren't selling enough, then the labels can't take that risk. It's really unfortunate how some of the smaller genres get squeezed. Black Prairie felt like a band that might break through some of those limitations; even though they are acoustic-based, they push the envelope on sonics, have clever arrangements, and unique songs. I love Black Prairie. Just hanging out with those people, you would want to be in business with them. That's how every signing for us has to work. We've had our share of assholes... some of them are worth it, but not so much these days.